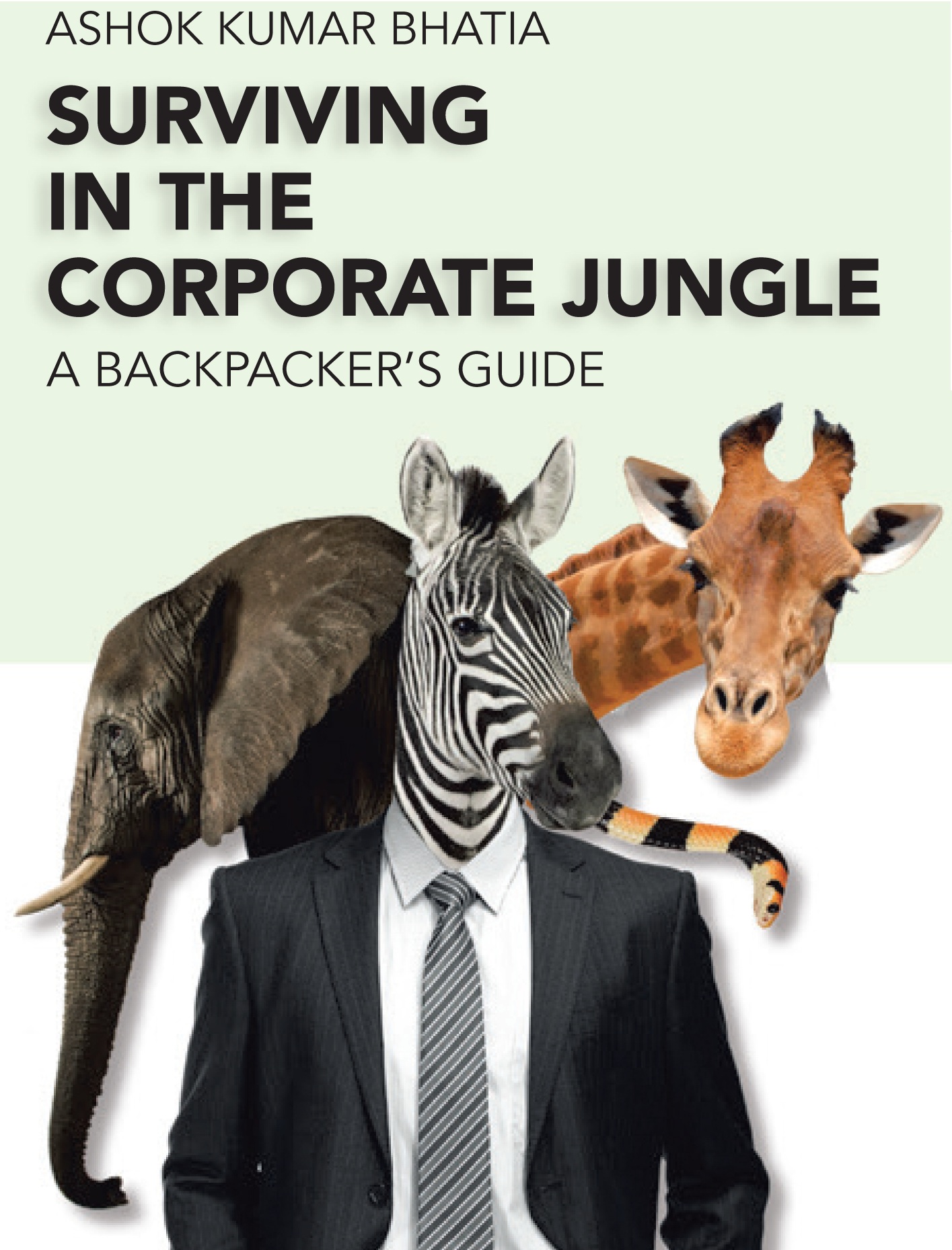

Wodehouse’s fiction, though celebrated chiefly for its whimsical aristocrats and shambolic bachelors, also furnishes a surprisingly detailed anatomy of the Edwardian and inter-war publishing world. He uses owners, publishers, and editors not merely as comic foils, but also nudges us towards a broader meditation on responsibility, power, and vocation. Through a kaleidoscope of characters—from absentee proprietors who think of their periodicals only while pronging a kippered herring on their plate with a gloomy fork, to editors who sacrifice sleep, dignity, and occasionally their trousers—Wodehouse rehearses the perennial tensions between commerce, conscience, and creativity.

Three Types of Owners

Wodehouse distinguishes three archetypes. The “absentee capitalist,” embodied by Mr Benjamin Scobell in The Prince and Betty, treats a publication as an elegant bauble within a far wider portfolio. The “romantic acquirer,” who buys a journal under the influence of either Cupid or a literary crush and sheds it as soon as the passion cools. Finally, we have the “hands-on mogul,” typified by Lord Tilbury of the Mammoth Publishing Company, who prowls city streets incognito lest aspiring scribblers hurl unsolicited manuscripts through omnibus windows. Lord Tilbury’s hunger for “juicy memoirs” and his ruthless eye on circulation figures epitomise the hard-nosed side of media ownership, reminding readers that even genteel magazines are ultimately businesses subject to profit and loss.

Editors: The Lion Kings

However, the slender shoulders on which the burden of keeping the publishing activity alive and kicking falls invariably happen to be those of the editors. They are the eager beavers who keep a sharp eye on the circulation figures and decide the nature and form of the content that gets routinely unleashed upon hapless readers like us. They happen to be industrious little creatures who work hard and shrink from the public gaze. They are the lion kings of their publishing fiefdom and are the masters of all they survey. Bosses love them when circulation figures show an upward trend. Yet, they are hated by authors whose manuscripts they keep throwing into the nearest dustbin in their office. In Plum’s world, alluded to above as Plumsville, editorial life is equal parts chess match and boxing bout; success demands both strategic foresight and literary prowess.

No case illustrates editorial resilience better than Aunt Dahlia Travers and her chronically unprofitable women’s weekly, Milady’s Boudoir. She marshals fox‑hunting grit, occasional grand larceny (commandeering a painting for a scoop), and the incomparable cuisine of Anatole to keep the presses rolling. Her magazine’s survival hinges not only on high finance but on familial diplomacy—extracting cheques from her dyspeptic husband, Uncle Tom, trading serial rights to pay printers, and manipulating Bertie Wooster into sartorial columns. Thus, Plum applauds tenacity while exposing the precarious economics of niche publishing.

Conversely, Cosy Moments—the ostensibly saccharine “journal for the home”—demonstrates how editorial ethos can metamorphose a title’s fortunes (Psmith, Journalist). When the fatigued Mr Wilberfloss departs for a rest cure, deputy Billy Windsor, aided and abetted by the restless Psmith, transforms the paper into a crusading watchdog. Exposés on New York tenement squalor replace homely recipes. A “fighting editor” is recruited to deter mob intimidation. Circulation soars, advertising revenue floods in, and Cosy Moments becomes “red‑hot stuff.” We discover the perils of mission-driven journalism: bribery, kidnapping, and street‑corner brawls lurk behind every righteous paragraph. Plum thus warns that social crusades, however noble, exact a steep personal price.

Hiring and firing supply further comic ammunition. Lord Tilbury, ever allergic to falling readership, sacks Monty Bodkin from Tiny Tots for peppering copy with whisky bottles and betting jargon, then dismisses Jerry Finch of Society Spice for failing to match Percy Pilbeam’s flair for fashionable scandal (Frozen Assets).

By contrast, editors like Joseph Kyrke of The Mayfair Gazette and Alexander Tudway of the Piccadilly Weekly (“The Kind-Hearted Editor”) discover that excessive kindness breeds calamity. Kyrke inherits the wreckage of predecessors who indulged amateur contributors; Tudway, having “improved” the dreadful manuscripts of Aubrey Jerningham and clan, ends up enslaved to an entire family of mediocre wannabe authors after marrying one to soothe her tears. Through these narratives, Plum demonstrates how editorial milk of human kindness could become a long-term liability.

A recurrent motif is the pursuit of sensational memoirs. Lord Tilbury’s frantic chase for the Hon’ble Galahad Threepwood’s reminiscences (Heavy Weather) and Florence Craye’s demand that Bertie incinerate Uncle Willoughby’s scandal-laden Recollections of a Long Life (“Jeeves Takes Charge”) dramatise both the cash value and moral hazard of exposé literature. Editors and owners salivate over sales figures, yet risk libel suits, family ruptures, and even the gobbling up of a manuscript by the Empress of Blandings.

Legal jeopardy surfaces again when Kipper Herring’s blistering anonymous review of Reverend Upjohn’s prep‑school history in the Thursday Review provokes threatened litigation (Jeeves in the Offing). Jeeves’s diplomatic ingenuity averts the writ, but the incident underscores an editor’s obligation to balance candour with accuracy.

Advertising masquerading as editorial content offers another ethical minefield. In “Healthward Ho,” quack doctors flood multiple periodicals with letters questioning the modern diet while discreetly touting their Spartan cure. Overworked editors struggle to distinguish between covert marketing and genuine debate, revealing how commercial pressures can erode editorial independence. Here, Plum, decades ahead of today’s “native advertising,” warns against blurred boundaries that compromise reader trust.

Romantic entanglements complicate these professional dilemmas. Editors woo rejected contributors to soften disappointment (“The Kind‑Hearted Editor”), propose marriage to avoid publishing dire stories, or, like Egbert Mulliner, fall in love only to discover their muse has begun penning bestselling fiction that traps them in promotional drudgery (“Best Seller”, the Mulliner version). We get to realise that the heart and the column space can conflict irreconcilably.

Sudden success in love enables Sippy, the editor of Mayfair Gazette, to stand up to his old headmaster. (“The Inferiority Complex of Old Sippy”)

Plum also cautions lovers about the perils of taking the romantic tips dished out by such columns as Doctor Cupid at face value. If so, much chaos, heartache, and hilarity could ensue (“When Doctors Disagree”).

Humour Laced with Social Conscience

Behind the laughter runs a social conscience. While Plum rarely preaches, the transformation of Cosy Moments and the tenement crusade reveal a genuine sympathy for the urban poor. He demonstrates that a periodical can transcend mere entertainment to serve as an agent of civic improvement, provided its guardians possess courage, networking prowess (even with underworld figures), and an unwavering purpose. The narrative demonstrates that there is indeed a socialistic streak in Plum, rebutting claims that he wrote solely for and about the idle rich.

Plum makes us realise that media, like all institutions, depend on people who must reconcile personal values with systemic demands. His brilliance lies in revealing that reconciliation as an endlessly inventive dance—sometimes dignified, often chaotic, always instructive.

More to be pitied than censured?

Having considered some of the journalistic escapades of quite a few of Plum’s characters, one may safely conclude that they are more to be pitied than censured.

When it comes to those who keep the giant wheels of the publishing universe spinning, Plum paints a broad canvas of the kind of constraints they work under. Financial pressures. A rigorous scrutiny of the content they decide to publish. Hiring the right talent and firing the deadwood is an area of concern. Interpersonal and legal challenges must be faced with a chin-up attitude. Ethical issues need to be tackled with aplomb. Relationships with authors and other stakeholders deserve to be managed with empathy and firmness. Cosying up to celebrity authors. If a major social concern is to be addressed, networking with the underworld and strongmen becomes crucial for achieving success.

Plum’s light-hearted depictions of publishing contain a rich commentary on leadership, ethics, and resilience. Owners personify strategic intent, whereas editors incarnate operational reality. He demonstrates that humane stewardship—anchored in empathy, clarity, and principled resolve—can turn the perilous art of publishing into an enduring public good.

While capturing the nuances of professional hazards faced by doctors, lawyers, bank managers, dog-biscuit marketeers, rozzers, detectives, principals, politicians, movie magnates, actors, musicians, artists, painters, accountants, secretaries, valets, butlers, cooks, gardeners, pig-keepers, et al, Plum’s sharp eye does not miss much. Likewise, when it comes to describing a journalistic life, he does not disappoint.

Note

- Inputs from Neil Midkiff, Eulalie (https://madameulalie.org/index.html), and Suryamouli Datta are gratefully acknowledged.

- The original article can be accessed at https://ashokbhatia.me/2025/02/19/the-myriad-challenges-faced-by-publishers-and-editors-in-plumsville.