Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan, known popularly as Mirza Ghalib, was not just a poet but a literary phenomenon whose works have transcended time and space. He lived during the turbulent period from 1797 to 1869. He ended up being a chronicler of the chaotic times faced by the country during the 1857 revolt when many of the markets and localities in Delhi vanished. The mansions of his friends were razed to the ground. He wrote that Delhi had become a desert. Water was scarce. The city had turned into “a military camp”. It was the end of the feudal elite to which Ghalib had belonged. He wrote:

है मौजज़न इक क़ुल्ज़ुम-ए-ख़ूँ काश यही हो

आता है अभी देखिए क्या क्या मिरे आगे

An ocean of blood churns around me – Alas! Was this all?

The future will show what more remains for me to see.

Having settled down in the Chandni Chowk area of Delhi, he experienced first-hand the demise of the Mughal dynasty and the rise of the British Empire in India. Within a few months of his death in 1869, Mahatma Gandhi, who eventually led India to its independence in 1947, was born, though far away in Gujarat.

Why Chandni Chowk? I guess it would have been a posh area of the walled city known as Shahajahanabad then. Proximity to the Mughal court might have also weighed on his mind. The ease of shopping might have been another consideration.

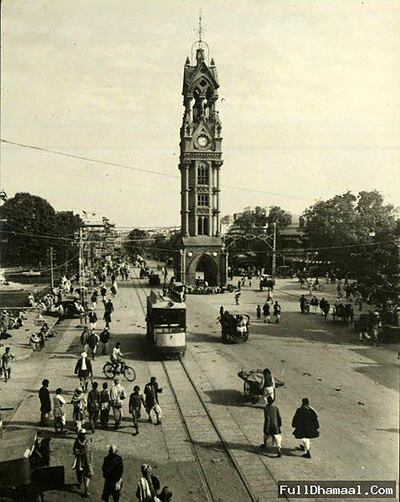

The Moonlit Square in Delhi

History buffs may recall that Chandni Chowk was built in 1650 by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, and designed by his daughter, Jahanara. The market was once divided by a shallow water channel (now closed) fed by water from the river Yamuna. It would reflect moonlight. Hence its name.

There were roads and shops on either side of the channel. Ladies from the royal family are said to have ventured out of the Red Fort to shop for jewellery, clothes, and accessories. The place continues to be a shoppers’ paradise and has also become the biggest wholesale market in North India.

Shakeel Badayuni, the poet and lyricist, beautifully captures the image of this shoppers’ paradise thus in one of his nazms, ‘Tasaadum’:

वो बाज़ार की ख़ुशनुमा जगमगाहट

वो गोश–आश्ना चलने फिरने की आहट

वो हर तरफ़ बिजलियों की बहारें

दुकानात की थी दुरबिया कतारें

That blissful glow of the market

That hustle-bustle of wide-eyed shoppers

A veritable spring of well-lit places

The endless rows of jewellery shops.

The range of products available is truly mind-boggling. Electrical goods, lamps and light fixtures, medical essentials and related products, silver and gold jewellery, trophies, shields, mementoes, and related items, metallic and wooden statues, sculptures, bells, handicrafts, stationery, books, paper and decorative materials, greeting and wedding cards, plumbing and sanitary ware, hardware and hotel kitchen equipment, all kinds of spices, dried fruits, nuts, herbs, grains, lentils, pickles and preserves/murabbas, industrial chemicals, home furnishing fabrics, including ready-made items as well as design services.

As to the mouth-watering sweets, savouries, and street food available in Chandni Chowk, right from the crispy jalebies of Dariba Kalan to the spicy chhole-chawal of Gol Hatti at Fatehpuri, full-length books alone may suffice.

Kuchas, katras, and havelis

The road now called Chandni Chowk has several streets running off it which are called kuchas(streets/wings). Each kucha usually had several katras (cul de sac or guild houses), which, in turn, had several havelis.

Typically, a kucha would have houses whose owners shared some common attributes, usually their occupation. Hence the names Kucha Maaliwara (the gardeners’ street) and Kucha Ballimaran (the oarsmen’s street).

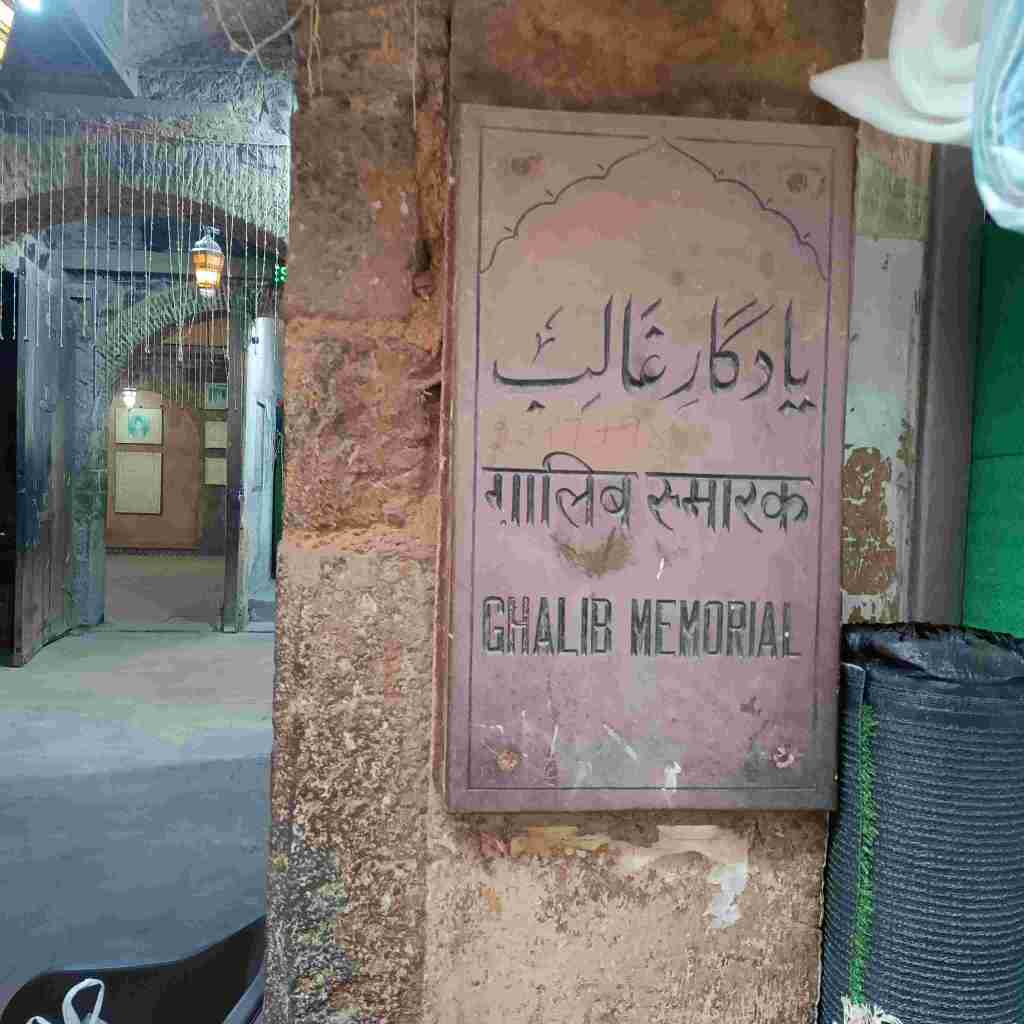

All this is not to say that there are no aspects of Chandni Chowk which one does not despise. One loathes its jostling crowds, its smells, its noises, its congested lanes, the mind-boggling variety of vehicles on its roads, its endless traffic snarls, its highly polluted air, its beggars trying to persuade perfect strangers to bear the burden of their maintenance with an optimistic vim, and its crowded pavements with aggressive sellers pouncing upon one to peddle their stuff. But if one has nerves of chilled steel and can manage all these with a chin-up attitude, one could eventually find one’s way to Ghalib ki Haveli, located in Gali Qasim Jan of Kucha Ballimaran.

As to Ghalib’s choice to live in Kucha Ballimaran, an area where oarsmen used to reside, one may merely surmise that as a creative genius of the literary world, he believed himself to be an oarsman, guiding his catamaran through the choppy waters of life!

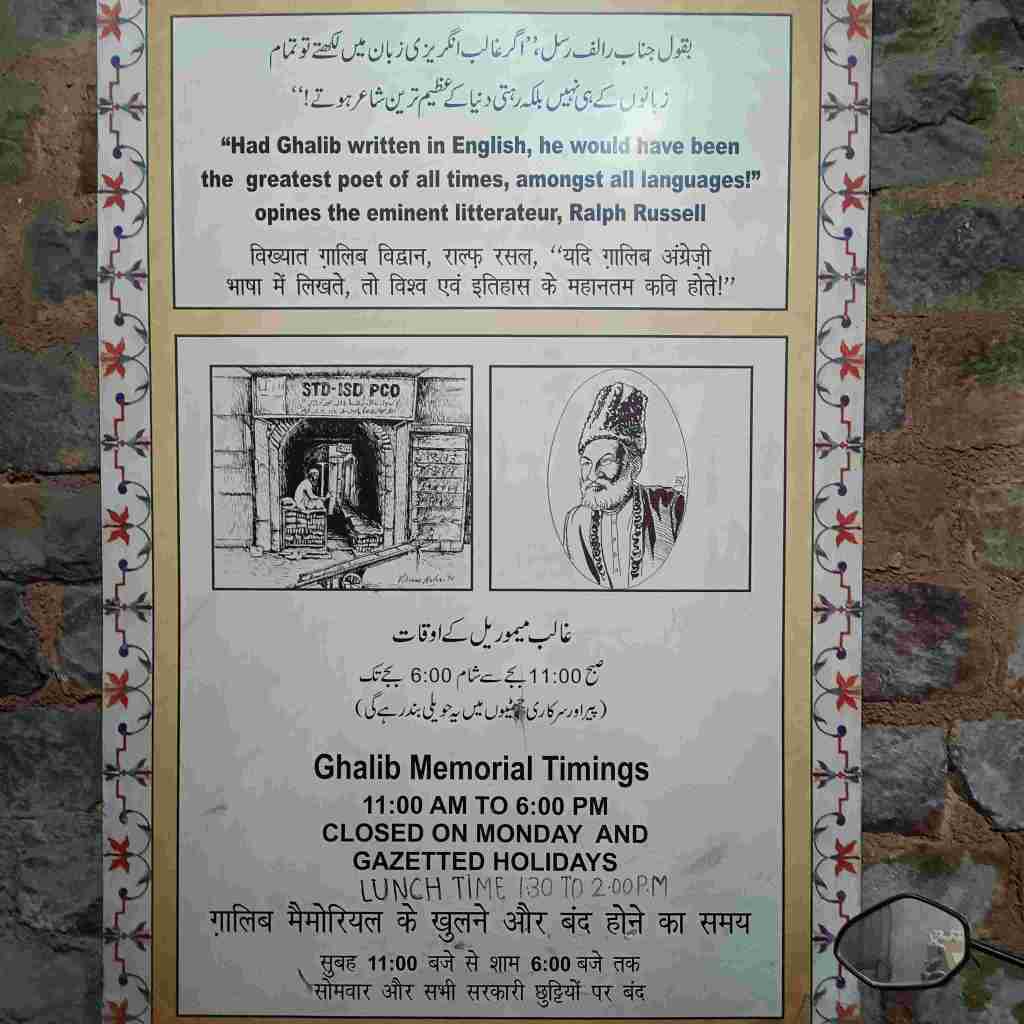

This place, where he lived from 1860 to 1869, till the time he breathed his last, has now been converted into a small museum of sorts. The main bust of Ghalib’s on display here has been gifted by Gulzar.

Mirza Ghalib

Born on December 27, 1797, in Agra, India, Ghalib’s life was marked by personal tragedies, political upheavals, and cultural transitions, all of which deeply influenced his poetic expression. Today, more than a century after his death, Ghalib remains one of the most celebrated poets in the Urdu and Persian literary traditions. His verses, rich with layers of meaning, continue to resonate with readers and scholars alike, offering insights into the human condition, love, pain, and the complexities of life.

Early Life and Personal Struggles

Ghalib was born into a family of Turkish aristocrats who had settled in India during the Mughal era. His father, Abdullah Beg Khan, was an officer in the army, but he died when Ghalib was just five years old. This left young Ghalib under the care of his uncle, Nasrullah Beg Khan, who also passed away a few years later. The early loss of his parents had a profound impact on Ghalib, and themes of loss, loneliness, and existential inquiry are recurrent in his poetry.

At the age of thirteen, Ghalib was married to Umrao Begum, a match arranged by his family. However, the marriage did not bring him the solace one might expect. Ghalib’s domestic life was fraught with tensions, and he found little happiness in it. None of his seven children survived beyond infancy. His financial struggles added to his woes, as he never held a stable job and relied on royal patronage, which was inconsistent at best.

The idea that life is one continuous painful struggle that can end only when life itself ends, is a recurring theme in his poetry. Consider this:

जब ज़िंदगी की क़ैद और ग़म का बन्धन एक ही है तो…

मरने से पहले आदमी ग़म से निजात पाए क्यूँ ?

The prison of life and the bondage of sorrow are the same,

Why should man be free of sorrow before dying?

Ghalib’s Literary Genius

Despite his personal hardships, Ghalib’s intellectual and poetic prowess blossomed. He was a polyglot, proficient in Urdu, Persian, and Turkish, and his poetry is a testament to his erudition. Ghalib’s work in Persian is extensive, but it is his Urdu poetry that has earned him eternal fame.

Ghalib’s ghazals are celebrated for their depth and complexity. A ghazal is a poetic form consisting of rhyming couplets and a refrain, with each line sharing the same meter. Ghalib mastered this form, infusing his verses with profound philosophical reflections, emotional intensity, and linguistic ingenuity. His poetry often grapples with the paradoxes of existence, the transience of life, and the elusive nature of love.

In keeping with the conventions of the classical ghazal, in most of Ghalib’s verses, the identity and the gender of the beloved are indeterminate. The critic/poet/writer Shamsur Rahman Faruqui explains that the convention of having the “idea” of a lover or beloved instead of an actual lover/beloved freed the poet-protagonist-lover from the demands of realism.

In one of my personal favourites on the tender emotion of love, he says:

उनके देखे से जो आ जाती है मुहं पर रौनक,

वो समझते हैं की बीमार का हाल अच्छा है.

My face is flushed with joy upon seeing my beloved,

Beloved mistakes my sickness to be a sign of good health.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Ghalib’s poetry is his exploration of the self. He delves into the intricacies of human identity, the soul’s relationship with the divine, and the quest for meaning in an indifferent world. For instance, in one of his famous couplets, Ghalib writes:

हज़ारों ख्वाहिशें ऐसी के हर ख्वाहिश पर दम निकले,

बहुत निकले मेरे अरमान फिर भी कम निकले

Thousands of desires, each worth dying for,

Many of them I have realised… yet I yearn for more.

This couplet reflects the insatiable nature of human desires, a theme that recurs throughout Ghalib’s poetry. His verses often portray a deep sense of melancholy, rooted in the understanding that the fulfilment of worldly desires is fleeting, and the ultimate truth lies beyond the material realm.

In many ways, the core of Ghalib’s poetry is not too far off from what Indian scriptures speak of.

The Philosophical Depth of Ghalib’s Poetry

Beyond his commentary on the socio-political changes of his time, Ghalib’s poetry delves into the philosophical. He was influenced by Sufism, a mystical Islamic belief system that emphasises the inward search for God and the personal experience of the divine. Sufi themes of love, union with the divine, and the eternal quest for truth permeate his poetry. However, Ghalib’s relationship with Sufism was complex. While he was drawn to its ideals, he also maintained a rational scepticism, often questioning established religious norms and dogmas. In one of his compositions, he mocks the hypocrisy of the preachers of Islam thus:

कहाँ मय-ख़ाने का दरवाज़ा ‘ग़ालिब’ और कहाँ वाइ’ज़

पर इतना जानते हैं कल वो जाता था कि हम निकले

What is the relation between the Preacher and the door of the tavern,

But believe me, Ghalib, I am sure I saw him slip in as I departed.

Ghalib’s poetry is also notable for its exploration of existential themes. He frequently contemplates the nature of reality, the impermanence of life, and the mysteries of the cosmos. His verses suggest a deep awareness of human knowledge’s limitations and the unknown’s vastness. In this sense, Ghalib can be seen as a precursor to modern existentialist thinkers, who similarly grappled with existence’s uncertainties.

Legacy and Influence

Ghalib passed away on February 15, 1869, in Delhi, but his legacy has only grown stronger with time. His poetry has been translated into numerous languages and continues to be studied, recited, and cherished by people across the world. Ghalib’s influence extends beyond literature; he has inspired musicians, filmmakers, and artists who have drawn upon his work to create new forms of artistic expression.

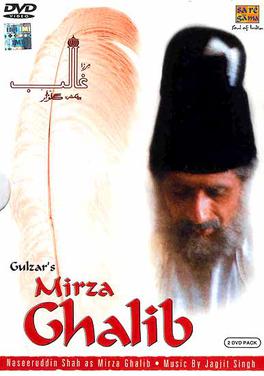

In India, Pakistan and elsewhere, Ghalib is not just a literary figure but a cultural icon. His ghazals are an integral part of the classical music tradition, and his life has been the subject of numerous plays, films, and television series.

Way back in 1954, Sohrab Modi gave us the movie Mirza Ghalib. Likewise, in 1961, Ataullah Hashmi of Pakistan gave us a movie on him.

In 1988, Gulzar came up with his television series which featured ghazals sung and composed by Jagjit Singh and Chitra Singh.

Various ghazal maestros like Mehdi Hassan, Iqbal Bano, Abida Parveen, Farida Khanum, Tina Sani, Noor Jehan, Suraiya, K L Saigal, Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhosle, Begum Akhtar, Ghulam Ali, Lata Mangeshkar, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, and Rahat Fateh Ali Khan have sung his ghazals.

Low on The Richter Scale of Comprehension

Modern-day communication thrives on simplicity. Complex ideas are conveyed in a language that the masses understand. In other words, verses which would rate extremely high on the Richter Scale of Comprehension. However, it appears that most of our famous poets and literary figures perfected the art which is just the opposite. Simple ideas couched in high-profile and complex language, which only those at the top of the Language Proficiency Pyramid might fathom. Perhaps such literary geniuses wish to differentiate themselves from the hoi polloi.

When it comes to this particular trait, Ghalib has good company. In Urdu poetry, he is not always easy to understand. The poems dished out by him are often tough to understand, enriched as they happen to be with words drawn from the Persian language. In Hindi, the poetry of Jai Shankar Prasad comes to my mind. In Sanskrit, Kalidasa often keeps a lay reader guessing. In English, Shakespeare always leaves me baffled.

Quite some time back, I had luckily invested in a book of his poems which has not only the Urdu versions but also the corresponding translations in English and Hindi. As and when the ambience is right, I would play one of the renderings of Jagjit Singh, but only after having spotted the poem in the book. With lights dimmed, and one’s favourite tissue restorative perched on the table nearby, I get to feel the intensity of his words and end up experiencing a bliss which cannot be described in words!

Mirza Ghalib’s poetry is a treasure trove of wisdom, beauty, and emotional depth. His verses transcend the boundaries of time, language, and culture, speaking to the universal human experience. Ghalib’s ability to articulate the complexities of life with such eloquence and grace makes him a timeless poet, one whose work will continue to inspire generations to come. His legacy, like his poetry, is eternal—a shining beacon in the vast ocean of literary history.

For all lovers of Urdu poetry, visiting Ghalib’s haveli is a pilgrimage of sorts.

Notes:

- Vignettes of Chandni Chowk and movie/series posters courtesy of the World Wide Web.

- Museum snaps taken by yours truly during a recent visit to the place.

- Inputs received from Colonel Vivek Prakash Singh (Retired), a renowned poet in Urdu and Hindi, are gratefully acknowledged.

- Thanks are due to Sanjay Bhatia and Ashok Kalra who enabled this visit!

Related Posts: