Related Posts:

Archive for the ‘A Vibrant Life!’ Category

(M)ad Men on our smart phones: Guest post by Suresh Subrahmanyan

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged Advertising, Diabetes, Diet Control, Lifestyle Diseases, Medicine on May 26, 2025| Leave a Comment »

Respecting the physical body – A managerial dilemma

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged linkedin, Management, Stephen Covey, White-collar productivity, Work Life Balance, Yoga on April 14, 2025| Leave a Comment »

अभी तुमने क्या देखा है? (हर्षिता वाजपेयी द्वारा रचित एक कविता)

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged Hindi, Poetry on December 17, 2024| Leave a Comment »

A visit to the birthplace of William Shakespeare

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged Birthplace, Blandings Castle, england, English, Jeeves, Literature, P G Wodehouse, Shakespeare, Shakespeare Centre, Stratford-upon-Avon, Travel, UK on November 15, 2024| 4 Comments »

In one of my earlier posts, I had already confessed that I do not suffer from an affliction which could best be alluded to as Shakespearitis. Given the limited supply of grey cells that nature has bequeathed upon me, I can be held to be a person who has a rather high Pumpkin Quotient. William Shakespeare’s literary outpourings need a much higher level of intellect to be understood and enjoyed. Unfortunately, that I simply do not possess. The stuff he has dished out is meant for brainy coves whose eyes shine with keen intelligence and whose heads bulge at the back, much like Jeeves’.

However, all this does not necessarily guarantee peace of mind. On the contrary, it makes life even more of a challenge. The brow is invariably furrowed. The heart is leaden with woe. This is so because he is to be found everywhere and is apt to spring surprises at all times, not a very pleasing prospect for a faint-hearted person like me. Surely, the fault lies in my stars.

My last trip to the United Kingdom proved to be no exception. A few days after I had unpacked the proverbial toothbrush, on a fine morning, my genial host had whipped up a sumptuous breakfast. While tucking into it with much gusto, I was feeling on top of the world. But just when you feel that life is a bed of roses, God is in heaven, and all is well with the world, Fate sneaks up from the back. Your Guardian Angel decides to proceed on a vacation. The blow falls, leaving one shaken and stirred.

I was informed that the birthplace of The Bard was just an hour’s drive from the town I was in at the time. The host, grace personified, thought it was his patriotic duty to drive me down to the place. Hiding my trepidation somehow, I consented. Well, one must be civil, you see.

As you like it

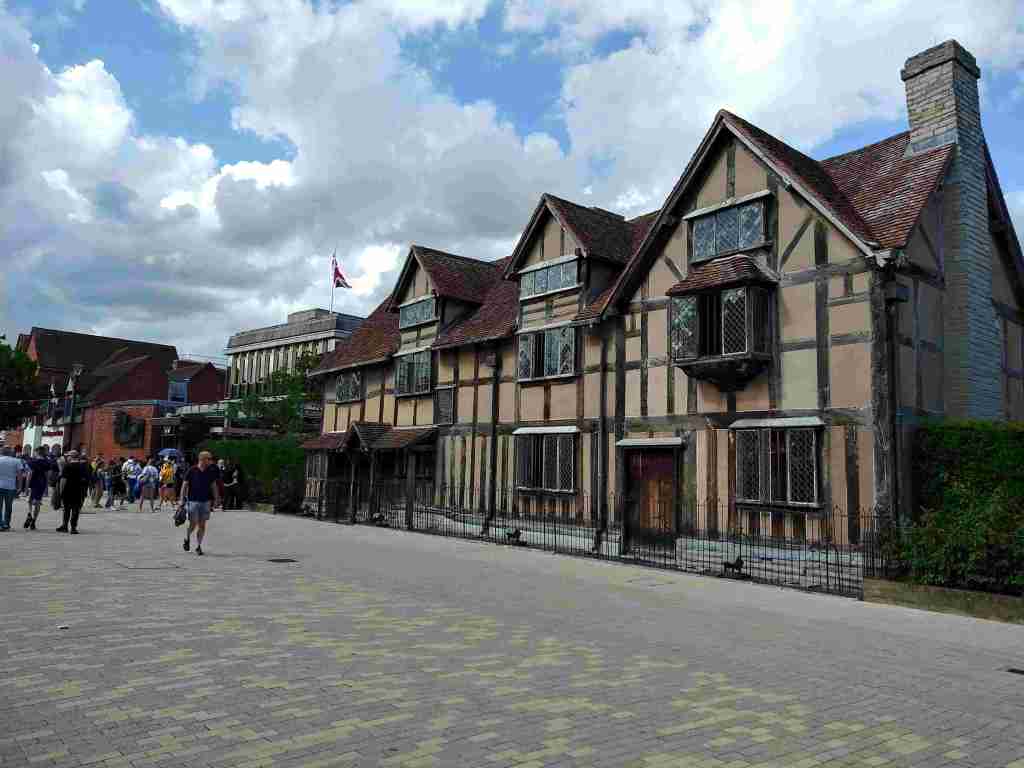

The journey to Stratford-upon-Avon was part of the charm. Surrounded by the serene English countryside, the town turned out to be a beautiful blend of cobbled streets, Tudor-style buildings, and winding pathways that echo centuries of history. The drive had the effect of converting my initial hesitation to a reluctant sense of anticipation.

Visiting William Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon proved to be like stepping into a time machine that transports one to the relatively simpler times of the late 16th century. Nestled in the charming market town in Warwickshire, England, the house on Henley Street is a unique time capsule that offers a glimpse into the life of Shakespeare and his family, set against the backdrop of a picturesque Elizabethan town. It is instructive to see how Henley Street has evolved over time.

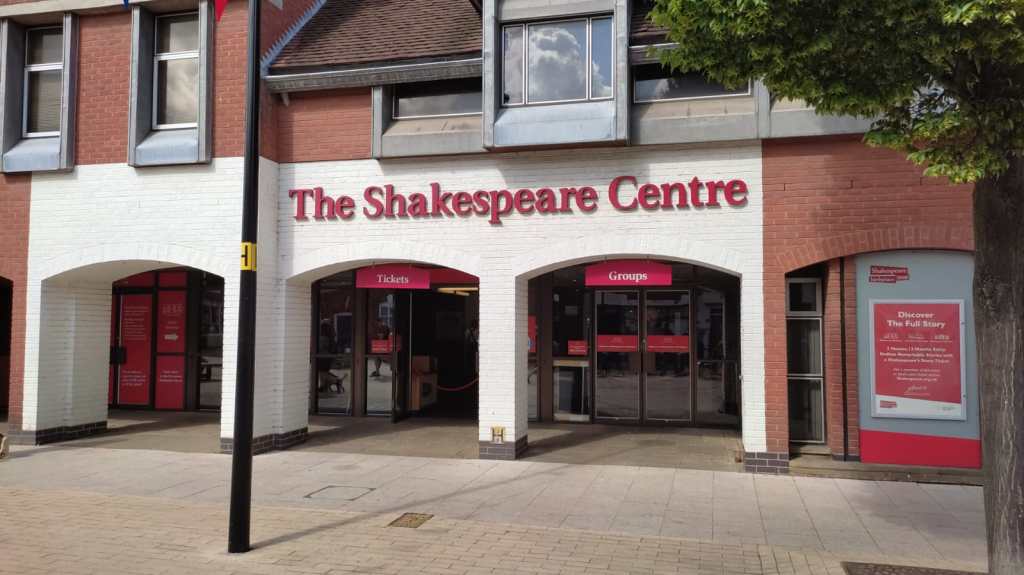

Despite being armed with a Google app, we had to repeatedly disturb a few locals to ask for directions to the Shakespeare Centre.

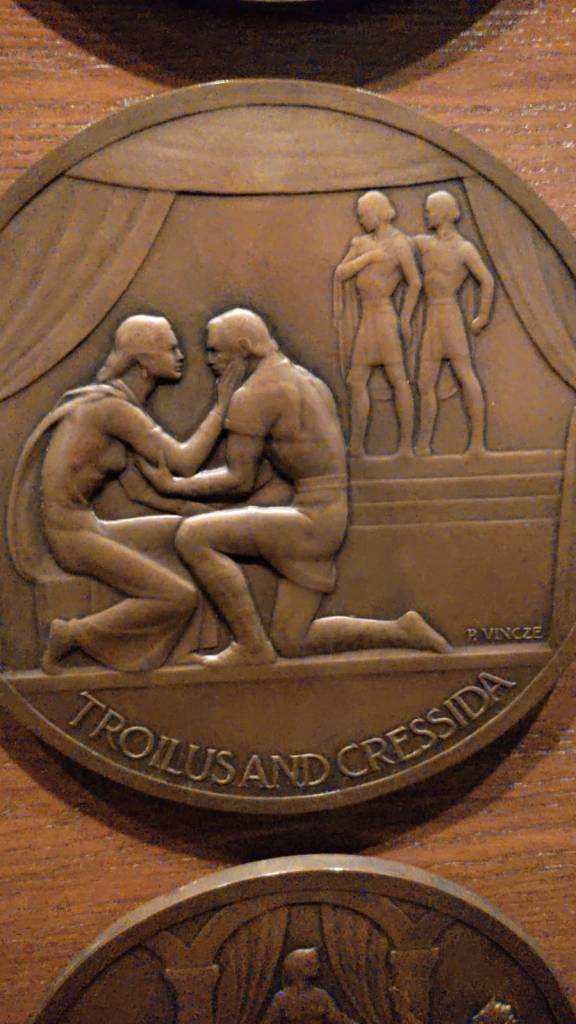

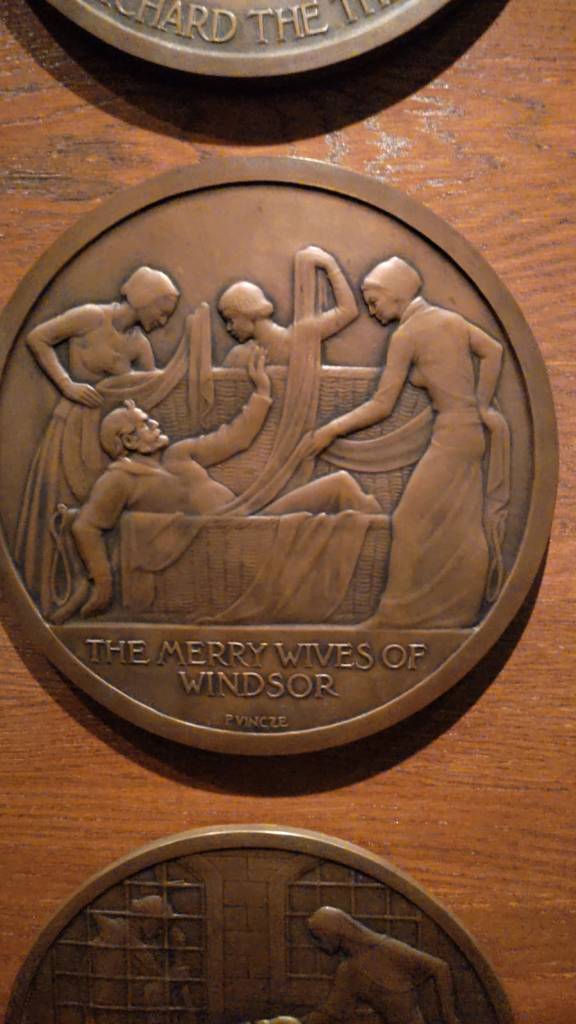

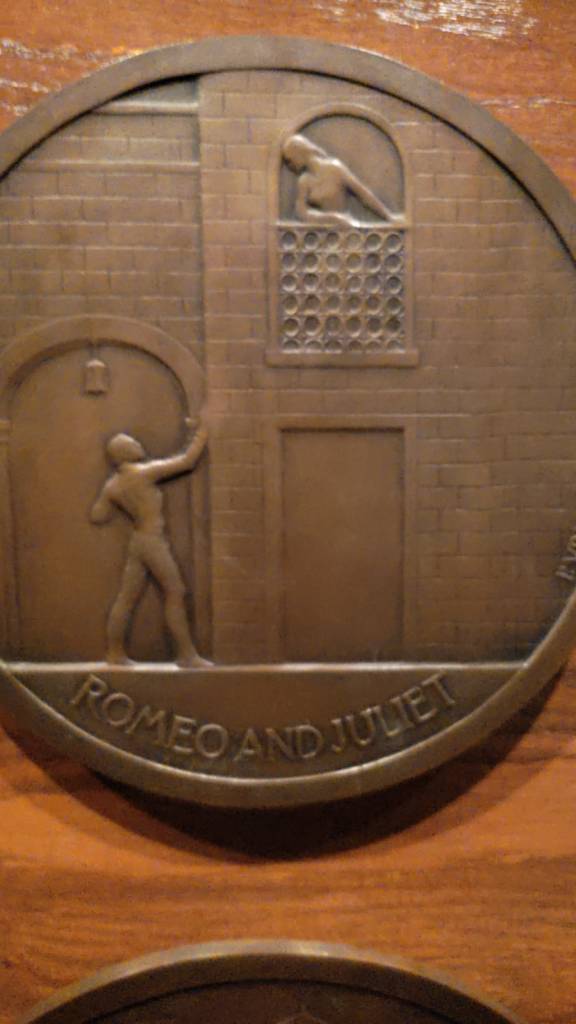

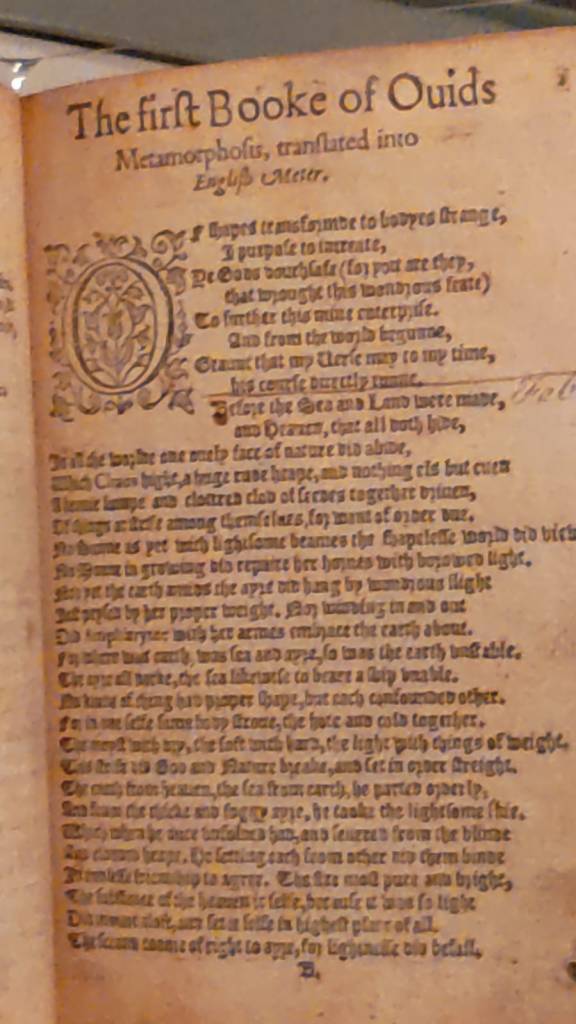

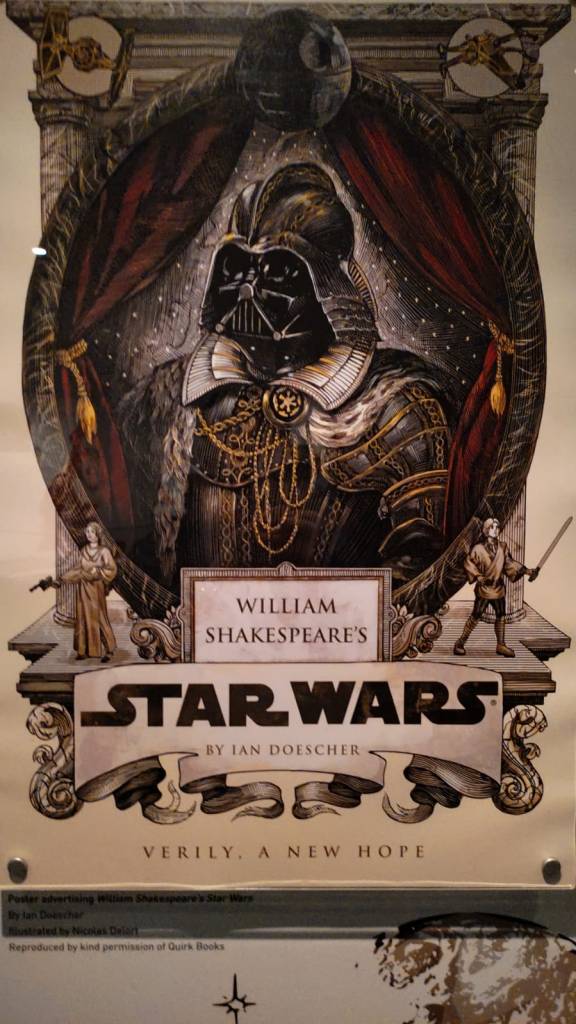

The modern visitor centre serves as an introduction to the playwright’s life, works, and the world in which he lived. It offers exhibits, displays of historical artefacts, and multimedia presentations that set the stage for the main attraction. One can see copper plaques devoted to many of his works, besides creative illustrations that connect him to the contemporary world.

The heaven’s lieutenants

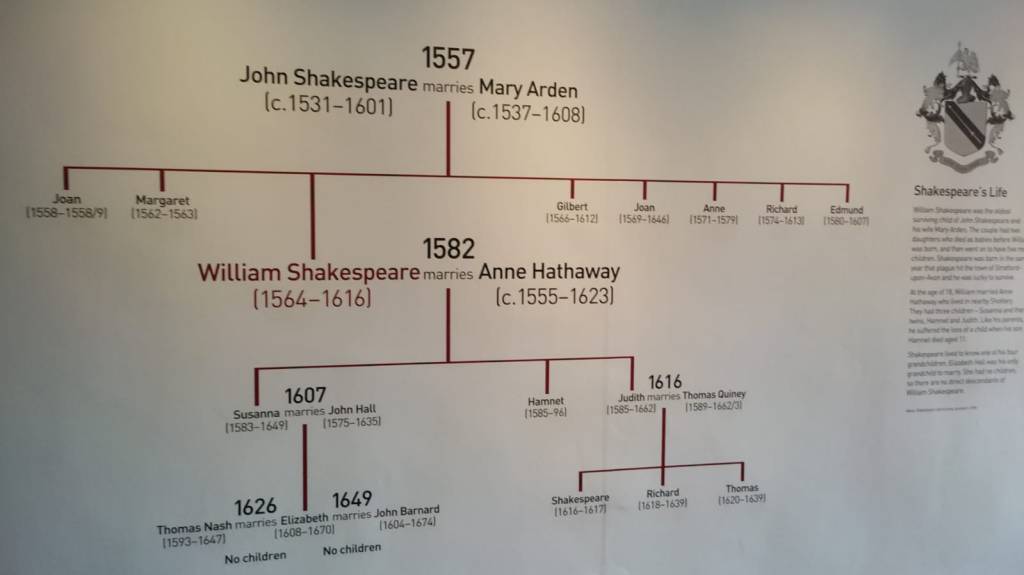

Before we move on to the birthplace itself, a family tree greets us. This is in the fitness of things, because The Bard placed a high premium on families. Some of you may recall this quote of his:

The voice of parents is the voice of gods, for to their children they are heaven’s lieutenants.

I am amazed to find that he was married to a lady by the name of Anne Hathaway; of course, not the Hollywood diva we happen to know since her The Devil wears Prada days!

Home: The place where he could waste his time!

The dwelling is a modest two-story, half-timbered house with a traditional wattle-and-daub construction typical of the Elizabethan era. Its architectural simplicity contrasts with the monumental legacy of the man who was born here in 1564. The house has been carefully preserved and restored to reflect the period as accurately as possible, down to the original furniture styles, wooden floors, and narrow doorways that would have been familiar to Shakespeare. Every corner of the home feels authentic, almost like the Bard himself or his family members might pop up at any moment. (Further details about the place can be found here)

Entering through the main door, visitors walk through the same rooms where young William would have spent his formative years. The ground floor houses a small enclosure where he would have met and entertained visitors. Then comes the main hall where the family would have gathered for meals, with a large hearth and a sturdy wooden table, showcasing how a typical middle-class family of that period lived.

One can readily appreciate how the house served as both a home and a business venue, as Shakespeare’s father, John Shakespeare, was a glove maker and wool dealer. His workspace, along with the tools of his trade, is laid out in one of the rooms, illustrating a connection between commerce and home life in the 16th century.

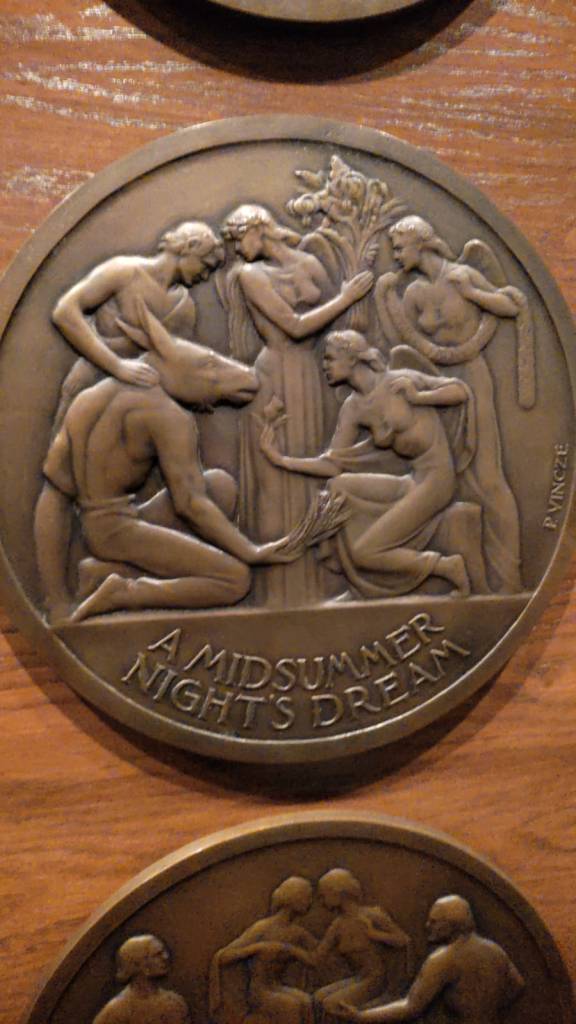

Upstairs, visitors can see the room traditionally thought to be the room where Shakespeare was born. The tiny window lets in a sliver of daylight, highlighting the simplicity of the furnishings and the room’s plain walls. One can see a tiny cradle where the young one might have had his maiden midsummer night’s dream.

A literary genius who was born great

Standing in that room, it’s hard to reconcile the humble surroundings with the profound literary genius that Shakespeare would become. But as a guide explains stories from Shakespeare’s early life, you get a sense of the young boy’s curiosity and imagination—qualities that must have been nurtured in this very place. Surely, he was not someone who became great, or upon whom greatness was thrust by his Guardian Angels. Indeed, he was born great.

The garden outside the house is another lovely feature. To a fan of P G Wodehouse, it sounds like a miniature version of the ones at Blandings Castle. It is filled with plants and flowers that are mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets. Walking through, you may recognize some of the herbs and flowers—like rosemary and pansies—from his writings. There is a sense that these natural elements inspired him, giving rise to his poetic descriptions of the natural world.

Understanding the world that shaped him makes it easier to understand how his plays reflected both the universality of human nature and the specific issues of his time.

To be or not to be

As the visit ends, scales have already fallen from one’s eyes. To be or not to be a fan of the Bard is a question which leaves one baffled, bewildered, confounded, confused, disconcerted, flummoxed, mystified, perplexed, and puzzled. In any case, one leaves with a newfound appreciation for the humble origins of William Shakespeare. His birthplace, though small and unpretentious, radiates with the legacy of a man whose works have shaped literature and drama worldwide and who is revered for his unique contributions to the Queen’s language. I am sure that he must have enriched the language in a manner that might be vaster and deeper than those who have either preceded or succeeded him. But lesser mortals like me, surely at the bottom of the English Proficiency Pyramid, are apt to feel very dense while endeavouring to devour any of his works.

However, for literary coves and linguistic purists, Stratford-upon-Avon remains a pilgrimage site, a place that celebrates not just Shakespeare’s legacy but also the power of words and stories to transcend time and space.

P G Wodehouse was one of those who held the Bard in high esteem. He once said: “Shakespeare’s stuff is different from mine, but that is not to say that it is inferior.” His frequent use of Shakespearean phrases in his stories and books merely attests to the same. Those of you who wish to explore this subject further may find this link useful.

All is well that ends well

Visiting the birthplace of William Shakespeare is more than a historical tour; it’s a journey through the formative environment of a literary legend. It provides a tangible sense of where the world’s most celebrated playwright came from and reminds visitors of the timeless influence of Shakespeare’s words, which continue to resonate across the ages.

Note: Thanks are due to Dominique Conterno, my host in the UK, who enabled this visit.

Related Posts

Exploring the Depths of Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot”: Guest Post by Suryamouli Datta

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged Fyodor Dostoevsky, Literature, Movies, Russia, The Idiot on November 11, 2024| Leave a Comment »

Introduction

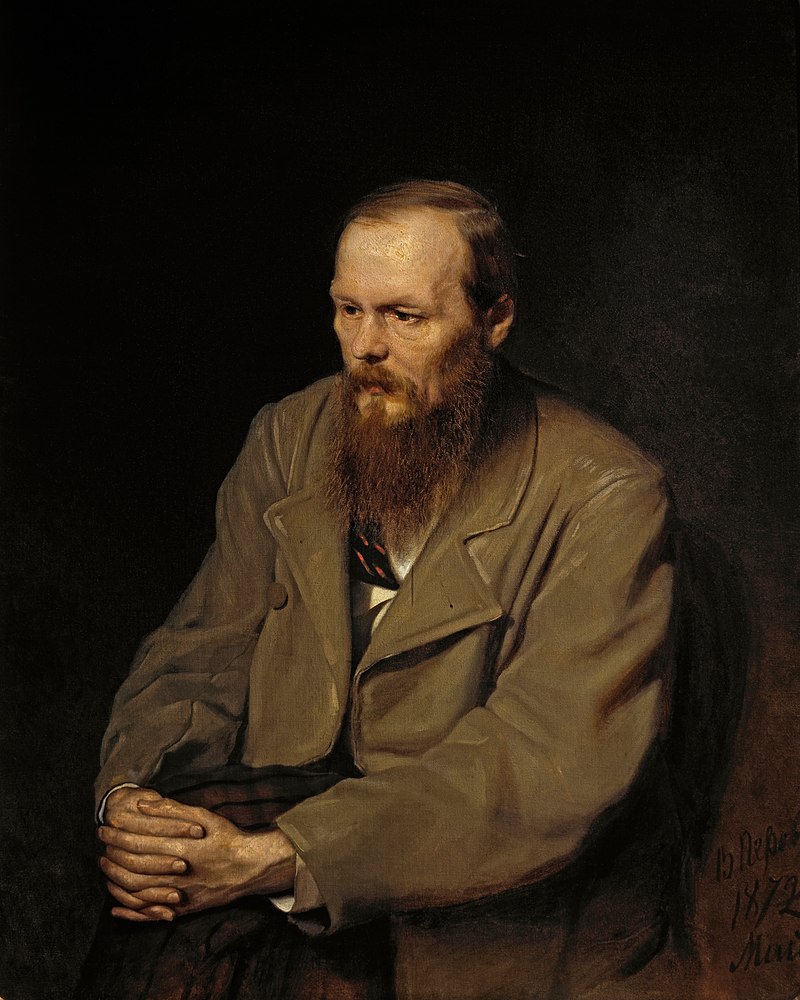

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot is a profound journey into the clash between innocence and the disillusionment of a morally complex society. First published in 1869, this novel remains a monument of philosophical inquiry and character depth. Dostoevsky, a visionary in Russian literature, was no stranger to human suffering and societal injustices. His own trials, including facing near-execution, find a voice in The Idiot. Through Prince Myshkin, Dostoevsky ventures into the possibility of purity in a world overcome by cynicism, greed, and moral ambiguity. Can innocence survive in a landscape marred by corruption? Dostoevsky invites us to ponder this question.

Dramatis Personae

- Prince Lev Nikolayevich Myshkin

Known as the “idiot” for his naive, unguarded nature, Myshkin stands as the embodiment of childlike idealism. He is described as a “positively beautiful man,” possessing a purity that starkly contrasts with the self-interest and moral ambiguity of those around him. Myshkin’s nature makes him vulnerable to manipulation, but his unwavering compassion and ability to forgive create an indelible impact on others. His words, “I’m sure you think me incredibly stupid, but I assure you that I understand many things” (Part 1, Chapter 7), resonate as an assertion of his deeper understanding beyond superficial judgments.

- Nastasya Filippovna

A tragic figure, Nastasya Filippovna is tormented by feelings of worthlessness and self-hatred. Her beauty captivates Myshkin and Rogozhin alike, but her traumatic past and self-destructive tendencies create a complex inner conflict. Her declaration, “I’m a nobody, a sick soul, I don’t deserve you” (Part 3, Chapter 3), reveals her deep-seated vulnerability and her struggle with self-acceptance, which drives much of the novel’s drama.

- Parfyon Rogozhin

Rogozhin, passionate and impulsive, serves as a dark counterpoint to Myshkin’s purity. His obsessive love for Nastasya Filippovna leads him down a destructive path, symbolizing love’s potential for ruin when tainted by possessiveness and jealousy. His volatile nature and capacity for violence create a tragic tension that culminates in inevitable disaster. Rogozhin’s intensity and Myshkin’s gentleness interact in a way that illustrates the broader dichotomy between purity and corruption.

- Aglaya Ivanovna

Representing idealism and the potential for happiness, Aglaya is drawn to Myshkin’s goodness but is constrained by societal expectations. Her struggle between her admiration for Myshkin and the weight of social pressure is poignantly expressed in her lament, “Why do they always make me do what I don’t want to do?” (Part 3, Chapter 8). Her character embodies the tension between personal desires and societal demands, further illustrating the novel’s exploration of unattainable ideals.

- Gavril Ardalionovich Ivolgin (Ganya)

An ambitious young man, Ganya seeks social mobility through a marriage to Nastasya Filippovna, driven by his desire for wealth and status. His conflicting feelings for Nastasya and his disdain for Myshkin’s ideals illustrate the personal costs of ambition and moral compromise.

- Ferdyshchenko

A minor character but essential for comic relief, Ferdyshchenko is outspoken and often disrupts social gatherings with his crude humour. He reflects the novel’s theme of hypocrisy by exposing the pretensions of those around him through his blunt honesty.

Plot Summary and Themes

The Idiot traces Myshkin’s return to Russia from a Swiss sanatorium, where his arrival in St. Petersburg sets off a series of events that unveil the moral and spiritual decay of the people around him. His genuine kindness and childlike honesty clash with society’s cynicism, resulting in misunderstandings and conflicts, especially around Nastasya Filippovna and Aglaya Ivanovna. Themes like innocence versus corruption, love’s complexities, and the ongoing struggle between good and evil make The Idiot a timeless masterpiece that critiques societal norms while examining the possibility of redemption. Dostoevsky’s philosophical views on justice and compassion, illustrated by Myshkin’s reflection on capital punishment, reveal his belief in a humane approach to morality—one that transcends the ordinary.

A pivotal moment in the book occurs during Nastasya’s dramatic party, where she throws 100,000 roubles into the fire, daring her suitors to retrieve it. This act symbolises her contempt for wealth and societal values, as she exclaims, “There’s no end to my vileness!” (Part 1, Chapter 15).

Myshkin on Capital Punishment

In The Idiot, Prince Myshkin’s commentary on capital punishment reflects Dostoevsky’s deep moral convictions and individual experiences. Myshkin recounts witnessing a guillotine execution in France, emphasising the psychological torment of the condemned rather than the physical pain. He argues that the preparations for execution—leading a man to the scaffold—are more horrific than the act itself, as they strip away humanity and instil profound fear. Myshkin’s belief that “thou shalt not kill” underscores his view that punishing evil with evil is fundamentally wrong, echoing Dostoevsky’s own traumatic near execution.

Historical and Biographical Context

Dostoevsky wrote The Idiot during a turbulent period in his life. After suffering through the death of his first daughter and facing financial difficulties, he sought to create a narrative that explored the possibility of a genuinely good and beautiful person. The novel was written in the late 1860s, a time of social and political upheaval in Russia, which is reflected in the characters’ struggles and societal critique.

Dostoevsky’s views on capital punishment were profoundly shaped by his firsthand experiences, particularly a mock execution he faced in 1849. Sentenced to death for his involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle, he was blindfolded and prepared for execution, only to be spared at the last moment. This psychological torture left a lasting impact, leading him to explore themes of suffering, compassion, and the moral implications of state-sanctioned death in his works, especially through the character of Prince Myshkin in The Idiot, who articulates the deep anguish of awaiting execution and the inherent cruelty of capital punishment.

Narrative Techniques and Character Relationships

Dostoevsky employs a variety of narrative techniques to bring depth to his characters and their relationships. The novel’s contrapuntal structure allows multiple voices and perspectives to coexist, creating a rich tapestry of conflicting ideologies and emotions. This approach provides insight into the characters’ inner lives and reflects the chaotic and multifaceted nature of human existence.

Prince Myshkin’s relationships with other characters are central to the novel’s exploration of moral integrity versus and corruption. His interactions with Nastasya Filippovna are particularly poignant, as he is drawn to her suffering and seeks to save her despite her self-destructive tendencies. Myshkin’s compassion for Nastasya is evident when he says, “I will follow you wherever you go, even to your grave” (Part 2, Chapter 7). This relationship highlights the tension between Myshkin’s idealism and the harsh realities of the world.

Similarly, Myshkin’s bond with Rogozhin is marked by a blend of friendship and rivalry, underpinned by their mutual obsession with Nastasya. Rogozhin’s passionate nature contrasts sharply with Myshkin’s gentleness, creating a dynamic that leads to tragedy. Rogozhin’s declaration, “You and I cannot live together; the one will destroy the other” (Part 4, Chapter 10), foreshadows the novel’s dramatic conclusion.

Myshkin’s relationship with Aglaya Ivanovna introduces another layer of complexity, as she represents a potential for happiness and normalcy. However, societal pressures and misunderstandings prevent their union, underscoring the novel’s theme of unattainable idealism. Aglaya’s struggle to reconcile her feelings for Myshkin with her family’s expectations is poignantly expressed when she asks, “Why do they always make me do what I don’t want to do?” (Part 3, Chapter 8).

Adaptations and Cultural Impact

Mani Kaul’s Ahamaq (1992) serves as a reinterpretation of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, adapting its themes to an Indian context. Both works explore the concept of “idiocy” through their protagonists—Prince Myshkin in The Idiot and his counterpart in Ahamaq, who struggles with epilepsy, often misinterpreted as madness.

While Dostoevsky’s narrative culminates in tragedy, reflecting societal cynicism, Kaul’s adaptation emphasises cultural nuances and the complexities of faith and desire within a contemporary Indian setting, offering a unique lens on the original themes of purity and delusion. In the television adaptation, Shah Rukh Khan portrayed the role of Rogozhin, Mita Vashisth the role of Nastasya, and M.K. Raina portrayed the role of Myshkin. Personally, I wish Shah Rukh had instead portrayed the role of Myshkin as he was doing enough negative roles on screen then.

Samaresh Basu’s novel Aparichita draws considerable influence from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. Both works explore themes of innocence, morality, and the complexities of human relationships. In Aparichita, the protagonist’s struggles mirror those of Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin, highlighting the tension between idealism and societal corruption. The narrative delves into the psychological landscapes of its characters, reflecting Dostoevsky’s polyphonic style, where multiple voices and perspectives coexist, enriching the emotional depth of the story. The film (1969) portrays Uttam Kumar as Rogozhin, Soumitra Chatterjee as Myshkin, and Aparna Sen as Nastasya. Soumitra Chatterjee’s performance in the movie was power-packed.

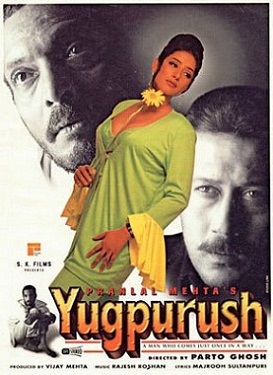

Additionally, the Bollywood film Yugpurush (1998) is based on Samaresh Basu’s novel Aparichita. The film starred Nana Patekar as Myshkin, Jackie Shroff as Rogozhin, and Manisha Koirala as Nastasya. The movie featured songs with music heavily influenced by Rabindra sangeet, composed by Rajesh Roshan. Yugpurush provides a fascinating lens on the themes of The Idiot, set within the Indian cultural milieu, and showcases the adaptability of Dostoevsky’s timeless themes.

Internationally also, The Idiot has inspired quite a few movies from such diverse countries as Russia, Germany, Japan, Estonia, and France.

The earliest example is that of Wandering Souls (German: Irrende Seelen), a 1921 German silent drama film directed by Carl Froelich and starring Asta Nielsen, Alfred Abel, and Walter Janssen.

Yet another example is that of L’idiot (1946), a French drama film which was directed by Georges Lampin and starred Edwige Feuillère, Lucien Coëdel and Jean Debucourt.

Conclusion

The Idiot remains a profound exploration of the human condition, examining the fragile balance between integrity and corruption. Dostoevsky’s masterful characterisations and narrative depth invite readers to ponder the true nature of goodness and the possibility of redemption. As we reflect on Myshkin’s journey, we are reminded of the enduring relevance of Dostoevsky’s vision of a world where compassion and integrity can shine, even in the darkest of times.

The Idiot remains as relevant as it was in Dostoevsky’s time. Humanity faces many challenges today. Wars. Poverty. Income disparities. Climate change. Challenges posed by rapid advances in technology. If we were to dig deeper, we are apt to discover that what we face is a crisis of leadership in all realms of human endeavour. The themes of authenticity, integrity, and morality have all been relegated to the background. Few big corporates rule the world. Social media puts blinkers on our eyes, masks the reality, and shapes our opinions. Forget carbon monoxide. Hate, cynicism, and hypocrisy also pollute the air we breathe in.

Myshkin’s journey resonates with contemporary readers facing a world where virtues are often overshadowed by self-interest and superficiality, reminding us of the power of goodness even in the darkest of circumstances. Dostoevsky’s portrayal of Myshkin’s kindness and compassion challenges readers to consider the value of empathy, sincerity, and integrity in our interactions with others.

References

- Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. Vintage Classics, 2003.

- CliffsNotes on The Idiot

- [Schlemiel Theory] (https://schlemielintheory.com/2014/11/26/what-happens-when-an-idiot-reflects-on-a-beheading-on-dostoevskys-reading-of-the

Related Post

Mirza Ghalib, the Timeless Voice of Urdu Poetry, and The Moonlit Square!

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged Ballimaran, Bollywood, British Rule, Chandni Chowk, Chitra Singh, Gulzar, Hindi, Jagjit Singh, Mahatma Gandhi, Mirza Ghalib, Mughal Dynasty, Naseeruddin Shah, Poetry, Shayari, Urdu on September 26, 2024| 9 Comments »

Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan, known popularly as Mirza Ghalib, was not just a poet but a literary phenomenon whose works have transcended time and space. He lived during the turbulent period from 1797 to 1869. He ended up being a chronicler of the chaotic times faced by the country during the 1857 revolt when many of the markets and localities in Delhi vanished. The mansions of his friends were razed to the ground. He wrote that Delhi had become a desert. Water was scarce. The city had turned into “a military camp”. It was the end of the feudal elite to which Ghalib had belonged. He wrote:

है मौजज़न इक क़ुल्ज़ुम-ए-ख़ूँ काश यही हो

आता है अभी देखिए क्या क्या मिरे आगे

An ocean of blood churns around me – Alas! Was this all?

The future will show what more remains for me to see.

Having settled down in the Chandni Chowk area of Delhi, he experienced first-hand the demise of the Mughal dynasty and the rise of the British Empire in India. Within a few months of his death in 1869, Mahatma Gandhi, who eventually led India to its independence in 1947, was born, though far away in Gujarat.

Why Chandni Chowk? I guess it would have been a posh area of the walled city known as Shahajahanabad then. Proximity to the Mughal court might have also weighed on his mind. The ease of shopping might have been another consideration.

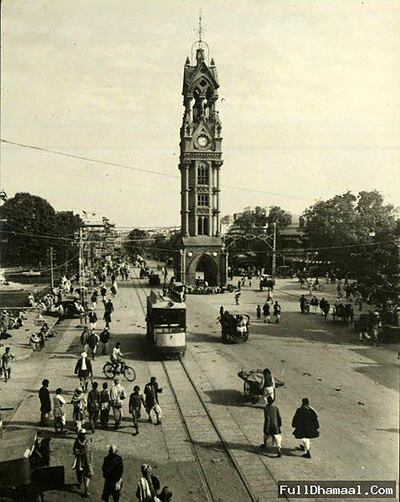

The Moonlit Square in Delhi

History buffs may recall that Chandni Chowk was built in 1650 by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, and designed by his daughter, Jahanara. The market was once divided by a shallow water channel (now closed) fed by water from the river Yamuna. It would reflect moonlight. Hence its name.

There were roads and shops on either side of the channel. Ladies from the royal family are said to have ventured out of the Red Fort to shop for jewellery, clothes, and accessories. The place continues to be a shoppers’ paradise and has also become the biggest wholesale market in North India.

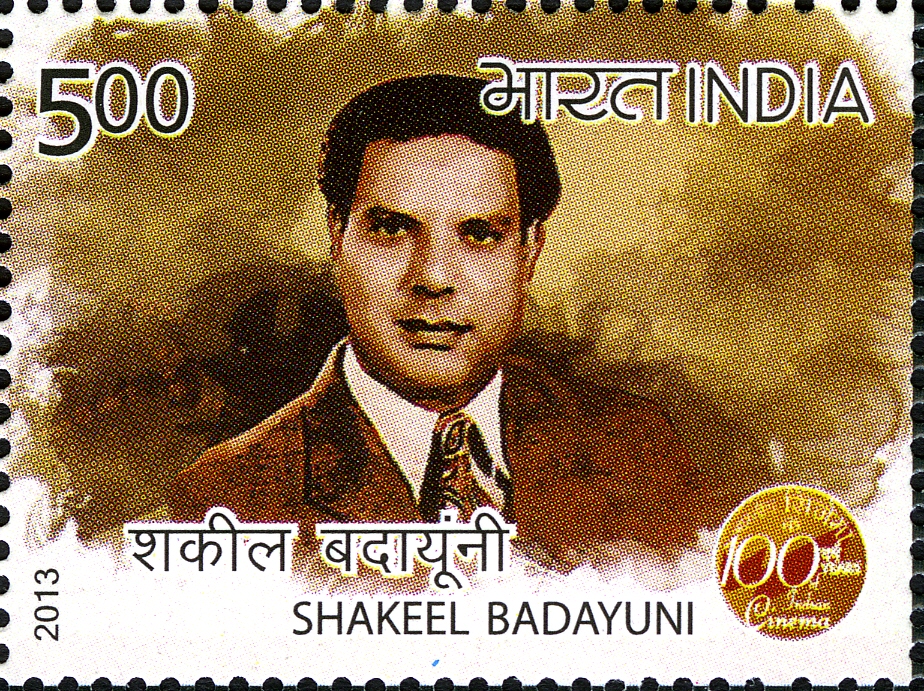

Shakeel Badayuni, the poet and lyricist, beautifully captures the image of this shoppers’ paradise thus in one of his nazms, ‘Tasaadum’:

वो बाज़ार की ख़ुशनुमा जगमगाहट

वो गोश–आश्ना चलने फिरने की आहट

वो हर तरफ़ बिजलियों की बहारें

दुकानात की थी दुरबिया कतारें

That blissful glow of the market

That hustle-bustle of wide-eyed shoppers

A veritable spring of well-lit places

The endless rows of jewellery shops.

The range of products available is truly mind-boggling. Electrical goods, lamps and light fixtures, medical essentials and related products, silver and gold jewellery, trophies, shields, mementoes, and related items, metallic and wooden statues, sculptures, bells, handicrafts, stationery, books, paper and decorative materials, greeting and wedding cards, plumbing and sanitary ware, hardware and hotel kitchen equipment, all kinds of spices, dried fruits, nuts, herbs, grains, lentils, pickles and preserves/murabbas, industrial chemicals, home furnishing fabrics, including ready-made items as well as design services.

As to the mouth-watering sweets, savouries, and street food available in Chandni Chowk, right from the crispy jalebies of Dariba Kalan to the spicy chhole-chawal of Gol Hatti at Fatehpuri, full-length books alone may suffice.

Kuchas, katras, and havelis

The road now called Chandni Chowk has several streets running off it which are called kuchas(streets/wings). Each kucha usually had several katras (cul de sac or guild houses), which, in turn, had several havelis.

Typically, a kucha would have houses whose owners shared some common attributes, usually their occupation. Hence the names Kucha Maaliwara (the gardeners’ street) and Kucha Ballimaran (the oarsmen’s street).

All this is not to say that there are no aspects of Chandni Chowk which one does not despise. One loathes its jostling crowds, its smells, its noises, its congested lanes, the mind-boggling variety of vehicles on its roads, its endless traffic snarls, its highly polluted air, its beggars trying to persuade perfect strangers to bear the burden of their maintenance with an optimistic vim, and its crowded pavements with aggressive sellers pouncing upon one to peddle their stuff. But if one has nerves of chilled steel and can manage all these with a chin-up attitude, one could eventually find one’s way to Ghalib ki Haveli, located in Gali Qasim Jan of Kucha Ballimaran.

As to Ghalib’s choice to live in Kucha Ballimaran, an area where oarsmen used to reside, one may merely surmise that as a creative genius of the literary world, he believed himself to be an oarsman, guiding his catamaran through the choppy waters of life!

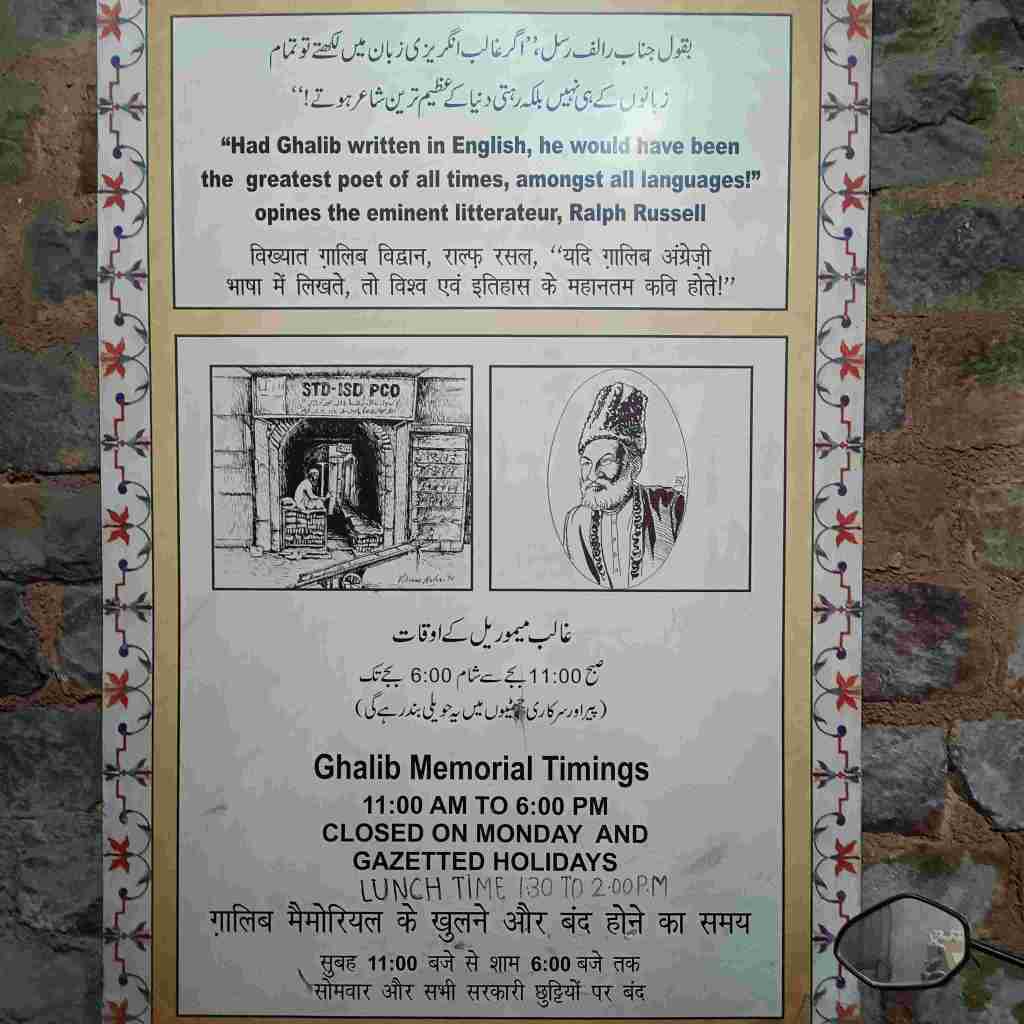

This place, where he lived from 1860 to 1869, till the time he breathed his last, has now been converted into a small museum of sorts. The main bust of Ghalib’s on display here has been gifted by Gulzar.

Mirza Ghalib

Born on December 27, 1797, in Agra, India, Ghalib’s life was marked by personal tragedies, political upheavals, and cultural transitions, all of which deeply influenced his poetic expression. Today, more than a century after his death, Ghalib remains one of the most celebrated poets in the Urdu and Persian literary traditions. His verses, rich with layers of meaning, continue to resonate with readers and scholars alike, offering insights into the human condition, love, pain, and the complexities of life.

Early Life and Personal Struggles

Ghalib was born into a family of Turkish aristocrats who had settled in India during the Mughal era. His father, Abdullah Beg Khan, was an officer in the army, but he died when Ghalib was just five years old. This left young Ghalib under the care of his uncle, Nasrullah Beg Khan, who also passed away a few years later. The early loss of his parents had a profound impact on Ghalib, and themes of loss, loneliness, and existential inquiry are recurrent in his poetry.

At the age of thirteen, Ghalib was married to Umrao Begum, a match arranged by his family. However, the marriage did not bring him the solace one might expect. Ghalib’s domestic life was fraught with tensions, and he found little happiness in it. None of his seven children survived beyond infancy. His financial struggles added to his woes, as he never held a stable job and relied on royal patronage, which was inconsistent at best.

The idea that life is one continuous painful struggle that can end only when life itself ends, is a recurring theme in his poetry. Consider this:

जब ज़िंदगी की क़ैद और ग़म का बन्धन एक ही है तो…

मरने से पहले आदमी ग़म से निजात पाए क्यूँ ?

The prison of life and the bondage of sorrow are the same,

Why should man be free of sorrow before dying?

Ghalib’s Literary Genius

Despite his personal hardships, Ghalib’s intellectual and poetic prowess blossomed. He was a polyglot, proficient in Urdu, Persian, and Turkish, and his poetry is a testament to his erudition. Ghalib’s work in Persian is extensive, but it is his Urdu poetry that has earned him eternal fame.

Ghalib’s ghazals are celebrated for their depth and complexity. A ghazal is a poetic form consisting of rhyming couplets and a refrain, with each line sharing the same meter. Ghalib mastered this form, infusing his verses with profound philosophical reflections, emotional intensity, and linguistic ingenuity. His poetry often grapples with the paradoxes of existence, the transience of life, and the elusive nature of love.

In keeping with the conventions of the classical ghazal, in most of Ghalib’s verses, the identity and the gender of the beloved are indeterminate. The critic/poet/writer Shamsur Rahman Faruqui explains that the convention of having the “idea” of a lover or beloved instead of an actual lover/beloved freed the poet-protagonist-lover from the demands of realism.

In one of my personal favourites on the tender emotion of love, he says:

उनके देखे से जो आ जाती है मुहं पर रौनक,

वो समझते हैं की बीमार का हाल अच्छा है.

My face is flushed with joy upon seeing my beloved,

Beloved mistakes my sickness to be a sign of good health.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Ghalib’s poetry is his exploration of the self. He delves into the intricacies of human identity, the soul’s relationship with the divine, and the quest for meaning in an indifferent world. For instance, in one of his famous couplets, Ghalib writes:

हज़ारों ख्वाहिशें ऐसी के हर ख्वाहिश पर दम निकले,

बहुत निकले मेरे अरमान फिर भी कम निकले

Thousands of desires, each worth dying for,

Many of them I have realised… yet I yearn for more.

This couplet reflects the insatiable nature of human desires, a theme that recurs throughout Ghalib’s poetry. His verses often portray a deep sense of melancholy, rooted in the understanding that the fulfilment of worldly desires is fleeting, and the ultimate truth lies beyond the material realm.

In many ways, the core of Ghalib’s poetry is not too far off from what Indian scriptures speak of.

The Philosophical Depth of Ghalib’s Poetry

Beyond his commentary on the socio-political changes of his time, Ghalib’s poetry delves into the philosophical. He was influenced by Sufism, a mystical Islamic belief system that emphasises the inward search for God and the personal experience of the divine. Sufi themes of love, union with the divine, and the eternal quest for truth permeate his poetry. However, Ghalib’s relationship with Sufism was complex. While he was drawn to its ideals, he also maintained a rational scepticism, often questioning established religious norms and dogmas. In one of his compositions, he mocks the hypocrisy of the preachers of Islam thus:

कहाँ मय-ख़ाने का दरवाज़ा ‘ग़ालिब’ और कहाँ वाइ’ज़

पर इतना जानते हैं कल वो जाता था कि हम निकले

What is the relation between the Preacher and the door of the tavern,

But believe me, Ghalib, I am sure I saw him slip in as I departed.

Ghalib’s poetry is also notable for its exploration of existential themes. He frequently contemplates the nature of reality, the impermanence of life, and the mysteries of the cosmos. His verses suggest a deep awareness of human knowledge’s limitations and the unknown’s vastness. In this sense, Ghalib can be seen as a precursor to modern existentialist thinkers, who similarly grappled with existence’s uncertainties.

Legacy and Influence

Ghalib passed away on February 15, 1869, in Delhi, but his legacy has only grown stronger with time. His poetry has been translated into numerous languages and continues to be studied, recited, and cherished by people across the world. Ghalib’s influence extends beyond literature; he has inspired musicians, filmmakers, and artists who have drawn upon his work to create new forms of artistic expression.

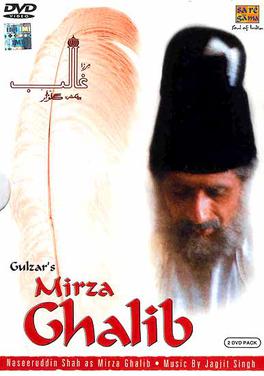

In India, Pakistan and elsewhere, Ghalib is not just a literary figure but a cultural icon. His ghazals are an integral part of the classical music tradition, and his life has been the subject of numerous plays, films, and television series.

Way back in 1954, Sohrab Modi gave us the movie Mirza Ghalib. Likewise, in 1961, Ataullah Hashmi of Pakistan gave us a movie on him.

In 1988, Gulzar came up with his television series which featured ghazals sung and composed by Jagjit Singh and Chitra Singh.

Various ghazal maestros like Mehdi Hassan, Iqbal Bano, Abida Parveen, Farida Khanum, Tina Sani, Noor Jehan, Suraiya, K L Saigal, Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhosle, Begum Akhtar, Ghulam Ali, Lata Mangeshkar, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, and Rahat Fateh Ali Khan have sung his ghazals.

Low on The Richter Scale of Comprehension

Modern-day communication thrives on simplicity. Complex ideas are conveyed in a language that the masses understand. In other words, verses which would rate extremely high on the Richter Scale of Comprehension. However, it appears that most of our famous poets and literary figures perfected the art which is just the opposite. Simple ideas couched in high-profile and complex language, which only those at the top of the Language Proficiency Pyramid might fathom. Perhaps such literary geniuses wish to differentiate themselves from the hoi polloi.

When it comes to this particular trait, Ghalib has good company. In Urdu poetry, he is not always easy to understand. The poems dished out by him are often tough to understand, enriched as they happen to be with words drawn from the Persian language. In Hindi, the poetry of Jai Shankar Prasad comes to my mind. In Sanskrit, Kalidasa often keeps a lay reader guessing. In English, Shakespeare always leaves me baffled.

Quite some time back, I had luckily invested in a book of his poems which has not only the Urdu versions but also the corresponding translations in English and Hindi. As and when the ambience is right, I would play one of the renderings of Jagjit Singh, but only after having spotted the poem in the book. With lights dimmed, and one’s favourite tissue restorative perched on the table nearby, I get to feel the intensity of his words and end up experiencing a bliss which cannot be described in words!

Mirza Ghalib’s poetry is a treasure trove of wisdom, beauty, and emotional depth. His verses transcend the boundaries of time, language, and culture, speaking to the universal human experience. Ghalib’s ability to articulate the complexities of life with such eloquence and grace makes him a timeless poet, one whose work will continue to inspire generations to come. His legacy, like his poetry, is eternal—a shining beacon in the vast ocean of literary history.

For all lovers of Urdu poetry, visiting Ghalib’s haveli is a pilgrimage of sorts.

Notes:

- Vignettes of Chandni Chowk and movie/series posters courtesy of the World Wide Web.

- Museum snaps taken by yours truly during a recent visit to the place.

- Inputs received from Colonel Vivek Prakash Singh (Retired), a renowned poet in Urdu and Hindi, are gratefully acknowledged.

- Thanks are due to Sanjay Bhatia and Ashok Kalra who enabled this visit!

Related Posts:

तसादुम (दुर्घटना): (शक़ील बदायूंनी)

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged Chandni Chowk, Hindi, Nazm, Shakeel Badayuni, Shayari, Tasaadum, Urdu on September 11, 2024| Leave a Comment »

वो सद-रश्क जन्नत वो गुलज़ार देहली

वो देहली जो फ़िरदौसे–हिंदोस्ताँ है

वो मजमुआ-ए-हुस्नो अनवार देहली

वो देहली के जिसकी ज़मीं आस्माँ है

वही जिसने देखे हैं लाखों ज़माने

सुने हैं बहुत इन्क़लाबी फ़साने

जहाँ दफ़्न हैं सैकड़ों ताज वाले

दो–रोज़ा हुकूमत के मैराज़ वाले

वहाँ शम्मा जलती है धीमी–सी लौ की

जहाँ जल्वारेज़ी है तहजीबे–नौ की

वहीं की ये दिल दोज़ रूदाद सुनिये

जहाने–अलम–ज़िक्रे बेदाद सुनिये

शफ़क से पहर के ठिकाने लगी थी

सियाही फ़िज़ाओं पे छाने लगी थी

फ़लक पर सितारे चमकने लगे थे

मुहब्बत के मारे बहकने लगे थे

वो बाज़ार की ख़ुशनुमा जगमगाहट

वो गोश–आश्ना चलने फिरने की आहट

वो हर तरफ़ बिजलियों की बहारें

दुकानात की थी दुरबिया कतारें

ये मंज़र भी था किस कदर कैफ़–सामाँ

ख़ुदा की ख़ुदाई थी जन्नत बदामाँ

सड़क पर कोई रह–रू–ए कुए जाना

चला जा रहा था ख़रामा ख़रामा

इधर राह पर नौजवाँ जा रहा था

उधर कोई मोटर चला आ रहा था

ये गाड़ी न थी जो चली आ रही थी

हक़ीक़त में जन्नत खिंची आ रही थी

कोई क्या बताये कि जन्नत में क्या था

वही था जो अब तक न देखा हुआ था

वो हुस्ने–मुक़म्मिल वो बर्के–मुजस्सिम

वो जिसके तसव्वुर से भी दूर हो ग़म

वो इक पैकरे–सादगी अल्लाह–अल्लाह

वो नाज़ुक लबों पर हँसी अल्लाह–अल्लाह

सरापा मुहब्बत सरापा जवानी

सितम उसपे साड़ी का रंग आस्मानी

वो रह रह के आँचल उठाने का आलम

वो हँस–हँस के मोटर चलाने का आलम

ये आलम बज़ाहिर फ़रेबे नज़र था

कि बस एक लम्हे में रंगे–दिगर था

न बश्शाश चेहरा न लब पे तबस्सुम

सुकून आश्ना था अदाये तकल्लुम

गिरा बारियाँ दिल को शर्मा गई थीं

निगाहों पे तारीकियाँ छा गई थीं

हुये सनफे नाज़ुक के होशो ख़िरद गुम

ज़ुबाँ ने पुकारा ‘तसादुम–तसादुम‘

ये मंज़र भी था किस कदर वहशत अफ़्जा

कि मोटर सरे राह ठहरा हुआ था

दिगर गूँ थी हालत तमाशाईयों की

ख़बर थी उन्हें दिल की गहराईयों की

इधर नौजवाँ खूँ बदामा पड़ा था

उधर एक मासूम क़ातिल खड़ा था

इधर रूह अज़्मे–सफ़र कर चुकी थी

उधर दिल पे वहशत असर कर चुकी थी

इधर मौत ख़ुद ज़िन्दगी अस्ल में थी

उधर ज़िन्दगी मौत की शक़्ल में थी

गरज़ खुल गई असलियत हादसे की

हुई मरने वाले की जामा तलाशी

पसे जेब क़ातिल की तस्वीर निकली

इलावा अज़ीं एक तहरीर निकली

तसल्ली हुई जान में जान आई

जो पर्चे पे लिखी इबारत ये पाई

“जफ़ाए–मुसल्सल से घबरा गया था

मैं ख़ुद आके मोटर से टकरा गया था“

टिप्पणियाँ:

- मेरे दिवंगत पिताजी मुझे बचपन में बताते थे की यह नज़्म चांदनी चौक दिल्ली में बहुत साल पहले हुई एक असली दुर्घटना पर आधारित है

- तस्वीर हिंदुस्तान टाइम्स के सौजन्य से

- विवेक प्रकाश सिंह का विशेष आभार

Of Consciousness and some properties of Light

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged Carl Jung, CEN, Consciousness, Diffraction, Diffusion, Duality, Light, Properties, Refraction, Sankhya Philosophy, Speed of Light on July 7, 2024| 2 Comments »

Trying to explain the concept of consciousness is not easy. Like the proverbial elephant and the seven blind men, each one of us has a different way of understanding and interpreting it. This note attempts to do it by using some of the properties which characterise one of the main energies of the universe, Light.

Being Invisible

Light makes us see the world around us. However, when traveling in a vacuum, it is invisible by itself. It is only when a ray of light encounters either dust particles or a surface which reflects it that we get to see an object. The object could be either organic, like a physical being, or inorganic, like a piece of rock.

Likewise, consciousness is not visible by itself. It is only when we come across some acts of a benevolent kind, something which soothes and uplifts our conscience, that we notice its presence. Moreover, if there is something happening around us those troubles us within, we notice its absence.

Those who notice either its presence or absence are the ones whose antennae are tuned to receiving and relaying the waves of consciousness. The German Psychoanalyst Carl Jung led us to believe that such persons are the ones who are not afraid of looking within and facing their own souls.

There’s no coming to consciousness without pain. No tree, it is said, can grow to heaven unless its roots reach down to hell. One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious. People will do anything, no matter how absurd, in order to avoid facing their own souls.

Conscious Leadership manifests itself through people and organisations that act in a conscious manner – a manager handling her team member facing a personal crisis in an empathic manner, a leader who is selflessly striving for an overall improvement of her country, or a whistle-blower who makes us sit up and take notice of the environmental damage a purely profit-driven business is doing. Like light, consciousness pervades the universe. Most of us are not aware of its presence. We are like a fish swimming in a lake which, when asked if water exists, may give us a puzzled look, wag its fins, shake its head in wonderment, and simply swim away.

However, if our receptors and antennae are tuned right, we can receive signals of consciousness and even radiate these further to those in our circle of influence.

The Visible and the Veiled Parts

Our senses have limitations. There is a range of wavelengths which alone is visible to the human eye. There is also a large part of the spectrum which remains veiled. A physicist would describe light as electromagnetic radiation. The latter is classified by wavelength into radio waves, microwaves, infrared, the visible part of the spectrum that we perceive as light, ultraviolet, X-rays, and gamma rays.

When scientists try to explain consciousness, they are usually looking at something which is a neurological phenomenon, occurring within the human brain. There are indeed times when our neural processes lead us to recognize a higher meaning in things. According to them, our 40 Hz oscillations happen to be the neural basis for consciousness in the brain. Quantum physicists believe that the Integrated Information Theory may enable humanity to explore the concept of consciousness better.

However, consciousness is immeasurable and cannot be explained with complicated mathematical models. Moreover, it is something that also exists beyond the realm of our physical frame. After all, human consciousness is but a smaller part of the larger consciousness of the universe. Perhaps, if Mother Nature had not protected us by limiting our senses, a majority of us, unable to handle the vast grandeur of its intrinsic beauty, would have become permanent residents of a lunatic asylum!

Even if we were to look within, a major part of us remains veiled. Consider the concept of five Koshas (sheaths) of the human body, of which we are aware of only the physical form. According to the Taittiriya Upanishad, an ancient Tantric yoga text, the Koshas are considered the five layers of energy. These sheaths or coverings are said to encase the Pure Consciousness (Purusha) or Self (atman). In Sanskrit, these are called Annamaya Kosha (food sheath), Pranamaya Kosha (sheath of prana or life), Manomaya Kosha (mind sheath), Vijnanamaya Kosha (knowledge or wisdom sheath), and Anandamaya Kosha (bliss sheath).

Duality and Multiplicity

Thinking from the perspective of quantum physics, the dual nature of radiation as both particle and wave challenges our conventional understanding of reality. It suggests that the universe is inherently interconnected and dynamic. This duality has an interesting similarity in neurology, where consciousness oscillates between discrete neurological events and a continuous flow of cognition. Just as particles and waves exist in a superposition until observed, consciousness can be perceived as a series of individual neural firings and a seamless experiential continuum. This analogy highlights the profound interconnectedness of physical phenomena and the human mind, suggesting a deeper, unified field where the boundaries between the material and the mental blend, opening new possibilities for exploring the mysteries of existence.

In its particle form, consciousness could be thought of as a germ of an idea nestled deep within us which connects us to our innermost Self. In this form, it is like a seed that is waiting to sprout, when given the right conditions of soil, water, air, and exposure to sunlight. We may also visualise it as a flame of light within us.

However, when an external occurrence becomes a catalyst, a wave of action gets initiated by us. This wave has a unique amplitude and frequency which is determined by our own personality. It travels to all those who happen to inhabit our circle of influence. Those who are receptive are impacted by it.

When many such persons with a matching frequency resonate with each other – driven by a common concern and a deep-seated desire to do something about it – come together, tribe comes into existence. Thus begins a change in the society’s attitudes and practices.

Yet another interesting perspective on the dual nature of things is provided by the Sankhya philosophy in Hinduism. It views reality as composed of two independent principles, Puruṣha (awareness) and Prakṛti (nature or matter, including the human mind and emotions).

Puruṣha is the witness-awareness. It is absolute, independent, free, beyond perception, above any experience by mind or senses, and is impossible to describe in words.

Prakriti is matter or nature. It is inactive, unconscious, and is a balance of the three guṇas (qualities or innate tendencies), namely sattva, rajas, and tamas.

Of Photons and Consciotons

The visible part of light is made up of photons. Likewise, one may surmise that the waves of consciousness comprise sub-atomic particles which, for the sake of convenience, we may call ‘consciotons’.

Since most of us have been brought up with an analytical mindset, we may find it difficult to either accept or visualise this. Perhaps we need to be patient and wait till the time a scientific study indicates the same!

The Components

When we pass a ray of light through a prism, it reveals its seven components, or different colours, which comprise it. These colours are Violet, Indigo, Blue, Green, Yellow, Orange, and Red.

Consciousness, under its humanly positive aspects, also has several components, many of which get revealed when it gets practised by an aspirant. Collective Good, Connection with the Universe, Clarity of Purpose, Compassion, Empathy, Humility and Righteous Integrity, and Self-awareness are some of these.

Refraction and Diffraction

When a straw is half-submerged in a glass container containing a liquid, the straw looks crooked. The higher the density of the liquid, the more the crookedness of the straw.

In the context of consciousness, let us imagine the glass container to be an individual, whose personality makeup determines the density of the liquid. A person whose thoughts, actions, and deeds happen to be pure would be one with the least possible density. The higher the level of impurity in a person’s thoughts, etc, the higher the density. If we were to consider the straw to be an idea steeped in consciousness, it becomes apparent that it would look crooked to a person with a negative mindset.

The path of light is invariably a straight and narrow one. But when it encounters an obstacle, it tries to get around the corners, a phenomenon which is referred to as diffraction. One of the outcomes of diffraction happens to be the beautiful rainbows that regale us from time to time.

What happens when we encounter challenges in life? Each challenge, whether in the official or the personal part of our lives, tests our tenacity, resilience, and courage. Those of us who have a sunnier outlook and a chin-up attitude try to get around it. In the process, we discover our inner strengths and reveal to those around us the kind of properties our consciousness is made up of. Down the road, when we look back at that experience, we may realise that our relation to the overall consciousness has changed. We appreciate the different colours which comprise our personal rainbows.

The Speed of Light

In the Newtonian world, the speed of light is treated as a universal constant. According to Einstein, when light rays pass nearby an object, these not only bend but even their speed gets reduced a bit. Quantum Physics also shows us how the speed of light may change under certain conditions. We have already seen how light travels at different speeds in different media, depending upon the density of the latter.

When a child is born, its heart is pure, sans any prejudices. It merely strives to seek adequate nourishment for the body. It lives in a higher state of consciousness. However, as the child grows, its personality starts shaping up, increasing the density of the medium, so to say. Depending upon the kind of nurturing it receives, the environment in which it grows, and the value eco-system it inherits, the speed at which it can either receive or radiate the waves of consciousness varies.

Individuals have different levels of receptivity to conscious ideas. Our receptivity gets determined by the way our personalities have shaped up over time. It can be readily appreciated that our receptivity to waves of consciousness varies in inverse proportion to the density of our personalities. The higher the density of one’s personality, the lower would be the receptivity. Thus, there are some who would embrace conscious ideas enthusiastically, and perhaps even start acting along those lines at the speed of light. However, quite a few others would resist such ideas, thereby slowing down the spread of waves of consciousness.

Perhaps the highest stage of consciousness leads us to enlightenment. There could be instances when this comes about instantaneously, either owing to a sudden spurt of intuition or an external trigger. Scales fall from our mental eyes. The mist in our thinking melts away and we are suddenly able to see things very clearly. A deep state of meditation could lead to clarity on a complex challenge one may be handling at the time. This instantaneousness is what the speed of light represents.

Lead, kindly light

As one of the essential elements of the universe, light brings joy, hope, and upliftment to our lives. The way it behaves helps us to understand yet another fundamental element of the universe, namely consciousness, better. The illusory absence of light results in darkness, depression, and hopelessness.

When the darkness and gloom of global warming, environmental degradation, wars, corruption, absence of values and ethics, and lack of concern for our fellow beings surround us, a ray of light and hope is what we seek. Enlightenment is what many of us aim for. A dash of consciousness is what we crave for.

Perhaps, this is so because our inner self is configured to yearn for bliss. Intrinsically, it appreciates the wonder of life and the beauty of life.

John H. Newman was not much off the mark when he said that:

Lead, kindly light, amid the encircling gloom

Lead thou me on

The night is dark, and I am far from home

Lead thou me on…

Likewise, we have an ancient Indian mantra which has been mentioned in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad:

असतो मा सद्गमय ।

तमसो मा ज्योतिर्गमय ।

मृत्योर्माऽमृतं गमय ॥

Asato mā sadgamaya,

Tamaso mā jyotirgamaya,

Mṛtyormā’mṛtaṃ gamaya.

From illusion lead me to truth,

From darkness lead me to light,

From death lead me to immortality.

May the inner flame of consciousness flickering within each one of us manifest itself in all our actions and spread its divine light all around, enabling humanity to lead a happier and more fulfilling existence.

Notes:

- Inputs from Dominique Conterno and Anju Kulshreshtha are gratefully acknowledged.

- Illustration courtesy Esther Robles.

- Both Dominique Conterno and Esther Robles are Co-founders of Conscious Enterprises Network (https://www.consciousenterprises.net)

Related Posts:

https://ashokbhatia.wordpress.com/2021/07/06/the-three-rs-of-consciousness-in-enterprises

https://ashokbhatia.wordpress.com/2021/09/02/towards-a-future-steeped-in-consciousness

Jousting with newspaper editors: Guest Post by Suresh Subrahmanyan

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged Blogging, Editors, Newspapers, Print Media, Publishing on July 1, 2024| 2 Comments »

Some Comments on the Bhagavad Gita

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged Bhagavad Gita, Comments, Gita, hinduism, Krishna, Spirituality on December 11, 2024| Leave a Comment »

The Gita is one of the clearest and most comprehensive summaries of the Perennial Philosophy ever to have been done.

Aldous Huxley

The Gita is a bouquet composed of the beautiful flowers of spiritual truths collected from the Upanishads.

Swami Vivekananda

My last prayer to everyone, therefore, is that one should not fail to thoroughly understand this ancient science of the life of a householder, or of worldly life, as early as possible in one’s life.

Lokmanya Tilak

The Gita is a book that has worn extraordinarily well, and it is almost as fresh and still in its real substance quite as new, because always renewable in experience, as when it first appeared in or was written into the frame of the Mahabharata.

Sri Aurobindo

When disappointment stares me in the face and all alone, I see not one ray of light, I go back to the Bhagavad Gita. I find a verse here and a verse there, and I immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming tragedies – and if they have left no visible, no indelible scare on me, I owe it all to the teaching of Bhagavad Gita.

Mahatma Gandhi

The teaching of the ancient battlefield gives guidance in all later days, and trains the aspiring soul in treading the steep and thorny path that leads to peace.

Dr Annie Besant

To my knowledge, there is no book in the whole range of the world’s literature so high above all as the Bhagavad Geeta which is treasure-house of Dharma not only for Hindus but for all mankind.

Madan Mohan Malviya

Related Posts:

Read Full Post »