Archive for the ‘What ho!’ Category

A Meeting of Plum Fans in New Delhi, India

Posted in What ho!, tagged P G Wodehouse, Humour, Fans, New Delhi, NCR on January 9, 2026| Leave a Comment »

Joy in the Evening – A meeting of Plum fans in Kolkata, India

Posted in What ho!, tagged Calcutta, Fans, Humour, India, Kolkata, Kwality, P G Wodehouse, Park Street, Travel on December 30, 2025| Leave a Comment »

The Gentle Decline of the Mumma’s Boy: Guest Post by Suryamouli Datta

Posted in What ho!, tagged Be!, Bertie Wooster, Dr Watson, Dracula, Humour, Jane Fonda, Jeeves, P G Wodehouse, Rocky Todd, Sherlock Holmes on November 14, 2025| Leave a Comment »

I. The Specimen at Breakfast

It is a truth universally whispered, if not acknowledged, that a man excessively fond of his mother is a developmental hiccup waiting to happen. He may be able to earn a salary, navigate traffic, even discuss the stock market — but the moment he mentions calling his mother, he is mentally filed away under Incomplete Specimen of Homo sapiens. This is especially so if the party of the other part happens to be either his spouse, or a live-in partner, or even a steady girlfriend.

Observe one in his natural habitat: spooning sugar into his morning tea with the precision of a laboratory technician, eyes flicking toward his phone — not for stock alerts or fantasy league scores, but to text “Good morning, Ma.” Evolution, one suspects, took a wrong turn somewhere between the Y chromosome and the apron string.

Society, ever alert to genetic inefficiency, has decided that this man must be mocked into extinction. He represents emotional dependency in an age that prizes self-sufficiency — the last candle in a world that prefers LED.

II. The Crime of Devotion

The modern “Mumma’s Boy” is a walking paradox: sentimental in public, decisive in none of the approved ways. He is not loud enough to be “alpha,” nor cool enough to be “detached.” He apologizes too quickly, remembers anniversaries unprompted, and believes emotions are meant to be acted upon, not merely analysed in therapy. In short, he is guilty of unedited humanity.

The crime, of course, is not affection itself — it is the refusal to outgrow it. Civilization applauds the man who rises above his upbringing, not the one who keeps it alive. The market rewards efficiency, not continuity. Our man, poor fellow, confuses tenderness with duty. He texts his mother daily because he has once lived through the silence that followed a missed call. He obeys her warnings about rain because he still remembers pneumonia from childhood. His obedience, mocked as immaturity, is often just trauma in polite clothes.

III. Society’s Favourite Punchbags

It is not that women despise such fussed-over persons — they simply find him inconvenient. For, how do you compete with someone’s story of origin? The Mumma’s Boy threatens the fragile ecosystem of modern romance: he already belongs to a woman who expects nothing, manipulates rarely, and forgives instinctively. It is not rivalry so much as redundancy.

Men, meanwhile, offer no solidarity. They, too, laugh — loudly — at the one who has not mastered emotional detachment. It is the laughter of the insecure, the sound of men terrified that affection might be contagious. Among themselves, they repeat that chilling corporate proverb of our age: Never mix feelings with efficiency.

And so, the mockery becomes ritual — a collective reassurance that we have evolved past dependence. What we really mean is: We have forgotten how to love without negotiation.

Sometimes it feels like that great trial on screen — twelve angry voices debating one man’s tenderness. The accused sits quietly, guilty of calling his mother, of speaking softly, while the jurors of modern life argue his fate. They call him dependent, unfinished, obsolete. And then Juror Eight raises his head, the lone dissenting conscience, asking what no one wants to: what if gentleness is not weakness but evidence of endurance? The others look away, impatient for a verdict. Empathy, as always, wins no medals — only the comfort of being right too early.

IV. The Concept of Extended Motherhood

The role of the mother does not always remain confined to one’s genetic parent. Motherliness is a sentiment which many other parties could end up showering upon the hapless male in question. It could extend its scope to include obdurate aunts, assorted females, and even valets and butlers who fuss over the object of their affections or masters in a way that could turn their biological mothers green with envy.

Consider Aunt Agatha who is forever keen to see Bertie Wooster getting married and keeping the Wooster dynasty alive and kicking. We also find Emerald Stoker who is one of those soothing, sympathetic girls you can take your troubles to, confident of having your hand held and your head patted. There is a sort of motherliness about her which you find restful. Not to forget the likes of Florence Craye and Vanessa Cook, who wish to raise the level of Bertie’s intellect. Elsewhere, at Deverill Hall, we get introduced to Esmond Haddock, who lives with his five overcritical aunts. They disapprove of his relationship with Corky Potter-Pirbright, because she is an actor.

Social status is no barrier to such strains of motherhood. Lord Marshmoreton must muster all his courage to stand up to his sister, Lady Caroline Byng, and declare a matrimonial alliance with his newly appointed secretary. In Blandings, Lord Emsworth finds it challenging to ignore the instructions of Lady Constance Keeble.

V. The Wodehouse Paradox

If literature had a patron saint for this tribe, it would surely be Bertie Wooster — the eternally well-meaning man who requires Jeeves not to outthink him but to save him from his own kindness. The Wodehouse universe never punishes the sentimental fool; it merely chuckles at him. And yet, who among us would rather live in Jeeves’s world — all logic, all restraint — than Bertie’s, where affection and absurdity coexist like bread and butter?

Jeeves’ is another shining example in the genre of extended motherhood. Just like one’s mother would decide what to wear on a certain occasion, his sartorial choices often conflict with those of his master. Whether it is about a white mess jacket with brass buttons or a pair of socks, the valet’s wish eventually prevails.

Our modern world has no use for Woosters. We have replaced them with algorithmic men — rational, optimized, and barely human. We speak of “emotional intelligence” but what we really mean is emotional management. In a quiet act of rebellion, the Mumma’s Boy continues to feel un-strategically. He loves inconveniently. His sentimentality, far from being regressive, is the only authentic protest left.

Somewhere in his subconscious, he still believes love should precede purpose — a belief that makes him unemployable in the economy of the heart.

VI. A Matter of Chromosomes and Consequences

If one were to approach this anthropologically, one might say the X and Y chromosomes never quite recovered from the moral confusion of modernity. Men were trained to conquer, but not to comfort; to provide, but not to preserve. Our subject — this peculiar holdover from an earlier blueprint — runs on an emotional operating system last updated when people still said ‘touch base’ unironically. Once, during an office migration, he was the only one who refused to upgrade to the new HR portal because his old login still worked—and he trusted that more than promises of “a better interface.” That, in essence, is his problem and his virtue: he sticks to what once kept him safe, even when everyone else has moved to cloud-based feelings. He still believes that obedience to his parent can be a form of strength — a legacy code he sees no reason to rewrite.

He is loyal to the first woman who ever loved him unconditionally, and that loyalty leaks inconveniently into other relationships. But instead of being admired for gratitude, he is censured, condemned, criticised, denounced, lambasted, lampooned, and pilloried for having a regressive outlook. A culture that venerates mothers in myth, after all, cannot quite stand sons who take the mythology literally. We worship the Mother Goddess with cymbals and incense, but flinch when a man lives by her word. The hymns say, “Matru Devo Bhava,” yet a son who truly believes it — who lets his mother’s advice outweigh his wife’s or boss’s — is dismissed as weak, regressive, or unmanly. In our stories, divine mothers bless their children’s wars and ambitions; in real life, they’re expected to stay politely out of them. The contradiction is cultural theatre — we deify motherhood, but only in the abstract. The moment reverence becomes obedience, the devotee metamorphoses into a punchbag. You see it everywhere — we stage plays about mothers’ sacrifices, post emotional tributes on Mother’s Day, and light lamps to divine matriarchs, yet flinch at the real-world consequences of such devotion. A son who quotes his mother is infantilized; one who disobeys her is applauded for “growing up.” It’s as if society prefers motherhood embalmed in marble, not breathing at the breakfast table. The worship is safe precisely because it’s distant. Up close, it demands humility — a virtue now branded as weakness.

And if that sounds too tragic, literature has always offered more consoling alternatives.

Even Bram Stoker, that cartographer of nightmares, gave the world a family of obedient sons. The Children of the Night in Dracula rise only when summoned, hunt only what their master decrees, and retreat at a single gesture. Strip away the gothic trappings, and they are curiously domestic creatures — well-mannered predators who would never dream of disobeying their guardian. Theirs is not rebellion but perfect filial discipline: a household of nocturnal Mumma’s Boys, loyal to a fault, beautifully house-trained in terror. The feudal spirit prevails.

And then, on a very different plane, comes Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Adventure of the Three Garridebs. When Dr Watson takes a bullet meant for another, Sherlock Holmes — that priest of logic, that marble statue of reason — forgets deduction altogether.

“You’re not hurt, Watson? For God’s sake, say that you are not hurt!”, he cries, tearing open the wound like an anxious mother examining a scraped knee. For one mortifying instant, the cold machine of intellect becomes the warm machinery of care. The great detective, so often accused of heartlessness, turns out to have been hiding a maternal core under his waistcoat. Even Doyle, perhaps without meaning to, admits that the purest love left to civilisation may no longer be romantic or heroic, but quietly maternal in spirit.

VII. The Inconvenient Truth

Here is the inconvenient truth: the Mumma’s Boy is not a moral failure. He is, in fact, society’s unwanted conscience. His instincts are outdated only because ours have calcified. While we train ourselves to love efficiently — in 300-character texts, in time slots between meetings — he still believes affection does not need an agenda. He may never lead revolutions or scale startups, but he will never ghost you either.

His so-called immaturity is often merely a refusal to evolve into emotional automation. After all, unlike in the digital logic-driven world that he inhabits, emotions are challenging to predict based on an algorithm or a mathematical equation. Mock him all you want, but he carries the faint, embarrassing reminder that tenderness used to be fashionable. Those who like him love him enough to let him enjoy the extra space for himself – the segment of his heart which has been lovingly occupied by someone from his childhood days.

So, to borrow from Rocky Todd, let him be!

“Be!

Be!

The past is dead.

To-morrow is not born.

Be to-day!

To-day!

Be with every nerve,

With every muscle,

With every drop of your red blood!

Be!”

VIII. The Last Gentleman

And so, the poor “Mumma’s Boy” trudges on — neither rebel nor saint, just an outdated model of emotional software running in a world obsessed with constant updates. He will continue to be the butt of jokes at brunches, kitty parties, and on social media panels about “modern masculinity.” But here is the twist: when the Wi-Fi of human connection inevitably goes down, it is usually this man — with his unglamorous emotional wiring — who still knows how to reconnect without instruction.

He will still call home, still remember birthdays, still believe that love does not need a disclaimer. Society may keep rewarding the loud and detached, but somewhere, between a performance review and a reminder to buy detergent, he’s the one holding civilisation together with nothing more than a well-intentioned affection and a decent phone plan.

Note:

- Inputs from Prodosh Bhattacharya are gratefully acknowledged.

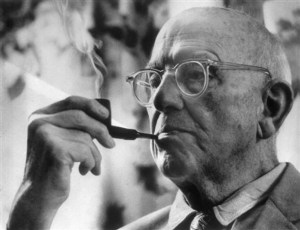

- Illustrations courtesy the World Wide Web.

Figures of Speech and Flowerpots: Guest Post by Captain Mohan Ram

Posted in What ho!, tagged Blandings, Flower pots, Leave it to Psmith, Necklace, Omar Khyyakm, P G Wodehouse, Psmith, Rubaiyat, Rupert Baxter on October 20, 2025| Leave a Comment »

We were subjected to a weekly torture session in school — a class called English Grammar. Imagine a twelve-year-old from Coimbatore in the deep south of India being bombarded with “subordinate clauses” and the “past pluperfect”! Those lessons were enough to drive most of us permanently away from English literature.

Then came a class on Figures of Speech using the opening couplets from Omar Khyyakm’s Rubaiyat (Translation – Fitzgerald), a revelation! For once, grammar turned into something alive, fun, colourful, and exciting. Let me share what I still remember from that day.

“AWAKE! for Morning in the Bowl of Night

Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight:

And Lo! the Hunter of the East has caught

The Sultan’s Turret in a Noose of Light.”

(Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, trans. Fitzgerald)

This isn’t just a sunrise — it’s a sunrise with flair, drama, and imagination!

Metaphor

• Bowl of Night — Night compared to a dark bowl holding the sky.

• Hunter of the East — The Sun as a hunter.

• Noose of Light — Sunlight as a glowing rope that ensnares towers.

Personification

Morning flings a stone, stars flee, light sets traps — the cosmos comes alive!

Symbolism

• Sultan’s Turret — Power and pride, humbled by the dawn.

Imagery

• Stars scattering like birds.

• Light roping in a turret.

• Night shattered like porcelain.

Who knew dawn could be so dramatic? Omar Khayyam turned a simple sunrise into a cosmic chase — and restored my faith in English grammar!

Years later, imagine my delight when I found that P. G. Wodehouse had stood this lofty imagery on its head — with his trademark anticlimax — in Leave It to Psmith.

The Scene

Poor Rupert Baxter is locked out after a failed attempt to locate Lady Constance’s missing necklace in a row of flowerpots. Exhausted and desperate, to attract attention he hurls flowerpsots through a window — which, alas, turns out to be Lord Emsworth’s bedroom! Finally, he falls asleep outdoors, only to be awakened by none other than Psmith himself.

Quote

“The spectacle of Psmith of all people beaming benignly down at him was an added offence.

‘I in person,’ said Psmith genially. ‘Awake, beloved, AWAKE! for Morning in the Bowl of Night has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight… The Sultan himself,’ he added, ‘you will find behind yonder window, speculating idly on your motives for bunging flowerpots at him. Why, if I may venture the question, did you?’”

Unquote

Only Plum could take Omar Khayyam’s exalted poetry and turn it into a dazzling anticlimax involving flowerpots and a furious peer of the realm.

That’s Wodehouse — the magician who could turn the sublime into the side-splitting.

(Captain Mohan Ram, ex Naval designer, eventually moved to the automobile industry where, if one may hazard a guess, he might have been designing some amphibian vehicles. His career trajectory followed the Peter’s Principle. He rose to senior positions, until finally retiring recently at the age of eighty four. He is currently cooling his heels, writing inane posts on Facebook.)

Related Posts:

Lost in the ‘pandal’ jungle of Kolkata during Durga Puja: Guest Post by Suryamouli Datta

Posted in What ho!, tagged Bertie Wooster, Humour, Jeeves, P G Wodehouse on September 26, 2025| Leave a Comment »

The Perks and Perils of Editing an Anthology

Posted in What ho!, tagged Anthology, Books, CEN, Editing, Essays, P G Wodehouse, Perils, Perks, Publishing, Writing on September 16, 2025| 2 Comments »

One of the lessons my Guardian Angels have taught me is that when one is overly critical of the task being done by someone else, they ensure that one willy-nilly ends up playing that very role for some time. Being in that person’s shoes (or sandals, if you prefer) helps one to realise exactly where the shoe pinches, literally as well as metaphorically. From being a critic, one turns up being a reluctant admirer of the art and craft of the task at hand. One develops empathy for the party of the other part. Scales fall from one’s eyes. It dawns upon one that the person performing the task in question is perhaps more to be pitied than censured.

Take the case of a husband who occasionally takes a jaundiced view of the quality of cooking of his spouse. However, after a heated argument, when she decides to go off in a huff to her parents’ house, all hell breaks loose. Regularly gobbling down instant noodles and takeaway food from nearby joints soon loses its charm. Deciding to take the matter into his own hands, he enters the kitchen arena, much like a Roman Gladiator showing up at the Colosseum. Finding the right raw materials and other ingredients in the kitchen becomes a major challenge. Locating either the right pots and pans or an appropriate ladle for whatever is planned to be dished out sounds tougher than overpowering a lion which has been deprived of its quota of vitamins for many days. Sweating profusely while seated on the dining table and trying to put some semi-cooked stuff down the hatch, he starts appreciating the cooking skills of his spouse. The post-cooking clean-up in the kitchen leaves him gasping for breath. Pretty soon, he decides to bury the hatchet and rush off to his in-laws’ place to charm the wife into accompanying him back to their abode. The dove of matrimonial peace restarts flapping its wings at home.

But I digress. After I hung up my corporate boots and decided to become an author, I had come to view editors of all sizes, shapes, and hues with a thinly veiled contempt. Most of them believed in following the dictum that silence conveyed a polite rejection. Even if they were to accept a manuscript for scrutiny, there was seldom a commitment as to when it might crawl up to the top of the pile on their cluttered tables. And yes, I dreaded the day when I would receive their detailed feedback. By then, they would have poked so many holes in the manuscript that it might as well be compared to Swiss cheese. Of course, the most traumatic experience was when I was asked to reduce the word length by close to 30% of what it was. To an author, it is akin to asking someone to perform a delicate surgery on oneself, sans anaesthesia of any kind!

However, my Guardian Angels soon decided to intervene and change my perspective. Somehow, I ended up becoming part of a three-member editorial team that has pious intentions of publishing a philosophical tome comprising as many as fifteen essays from as many authors located in different parts of the world.

For me, a voracious reader, it is obviously a pleasure to go through varying perspectives on the same subject. One’s mind opens up, much like a sunflower trying to soak in as much Vitamin D as possible. One’s outlook broadens. Each author’s voice is unique. The frequency, the amplitude, and the tone and tenor of each composition are different. At a casual glance, all these might sound like a cacophony of sorts. But together, they all generate a symphony of sorts, presenting a harmonious blend of the key message of the anthology.

Empathising with Editors

Thus, the task of editing offers quite a few perks. But it also makes one face many challenges in the process. Here is an indicative list of some of these faced by the team so far.

- Ensuring that the content of any contribution fits into the overall purpose of the collection.

- Maintaining the originality of the author’s voice, while suggesting improvements which would connect the narrative better to the key objective of the anthology.

- To improve the readability of a paper, each one needs to be checked and ranked on a hypothetical Richter Scale of Comprehensibility. Those scoring higher than a threshold must be politely advised to tone down the narrative.

- Having patience with contributors who are first-time authors. Supporting them to improve the general flow of the article. Assisting them in connecting disparate sections or paragraphs more smoothly.

- Even though all contributions may be in the same language, the sentence construction, the choice of words used, and the way of conveying an idea vary widely. This requires a type of verbal dexterity which could leave one fogged, nonplussed, and perplexed.

- Ensuring that a contributor is not trying to promote his/her own business interests through the paper submitted by them. One, that would be unethical. Two, if readers suspect that a commercial motive is embedded in any essay, our own credibility and brand image take a hit.

- In case an expert has contributed a paper on a subject which is not understood by any of the members of the editorial team, referring it to a domain expert for a peer review makes eminent sense. Coordinating between the author and the expert helps in bringing about a better balance in the paper.

- Since the idea is to deliver a book to our readers which does not leave them fretting and fuming over linguistic bloomers in the manuscript, the services of an external editor need to be hired. In many cases, this may entail a back-and-forth exchange of ideas between the author and the external editor. If the author has chosen to quote references and mentioned a few weblinks to support the arguments being advanced, a rigorous check of the same could be handled by him/her.

- With advances in technology, a basic check to ascertain the AI-infestation level of any essay needs to be considered a sine qua non.

It transpires that editors need to be made of sterner stuff. Overcoming our prejudices and being impartial does not come easily. A bulldog spirit is essential. Nerves of chilled steel are required for picking up something written by someone else and transforming it into the kind of stuff potential readers would gleefully lap up, much like your pet relishing a slice of fish.

Having undergone an instructive experience of this kind, one may safely conclude that editors are more to be pitied than censured.

In fact, it was this experience that prompted yours truly to publish a detailed blog post earlier, capturing the kind of challenges faced by the owners and editors of journals in the oeuvre of Sir P. G. Wodehouse.

Choosing a Title and Subtitle

Once the manuscript is almost ready, thoughts of the team obviously turned to the challenge of choosing an appropriate title and subtitle for the collection.

The snag we always come up against when deciding upon these can be summed up as an existential dilemma between two vastly different atmospheric levels – the troposphere, closer to the ground realities which are showcased by different articles, and the stratosphere, which denotes the loftier goals with which the anthology was conceptualised, to begin with. This deserves serious thought. Both must be catchy and readily comprehensible. It is something one does not want to go wrong about, because one false step and the whole compendium is sunk. If a lay reader, while searching for something fresh to devour, does not become curious about what a book is all about, and does not get a promise as to what precisely to expect, they could not be blamed for failing to get attracted to the offering. Their short attention span of a few seconds makes them move away to greener pastures. They simply walk out on one.

Thus, if the title represents the loftier goal of the anthology in a rather obtuse manner, the subtitle must hasten to clarify what it is all about and what it promises to deliver.

So, one needs to put one’s thinking cap on, surf through the internet to locate the titles and subtitles of comparable works, if any, and then make a judicious call. The last thing one wants is to leave one’s public at a loss, simply raising their eyebrows, twiddling their thumbs, and trying to figure out what one is talking about.

The Challenge of Whipping Up an Introduction

The existential dilemma mentioned above also pervades this aspect of the book. While crafting an introductory chapter to the collection of voices presented in the anthology, a balance needs to be struck between the stratospheric level of the high ideals which the book intends to convey to its readers and the tropospheric real-life situations reflected in the different papers presented therein. Not an easy task! Recalling that sordid experience, one could be forgiven for quivering like an aspen, if you know what I mean.

If one starts describing the contents of different papers in brief, one leaves the audience wondering where the collection is headed. Of course, one does it with the best of intentions, trying to provide a bird’s-eye view of the whole affair. But even the most conscientious readers could be left clueless as to what purpose will be served by their having to trudge through as many as fifteen odd essays, each having a different ‘intellectual density’, with few connecting points between them. They would miss the woods for the trees.

On the other hand, if one takes too long to capture the beauty of the woods, create an atmosphere, and state the loftier goals which prompted one to curate a delectable collection of so many essays, many readers may simply call it a day and quietly walk out on one.

Perhaps wisdom lies in putting the salient facts as briefly as possible and linking them to the overall purpose of the book, prompting the reader to go ahead and start exploring different chapters, either sequentially or otherwise, one by one. It can be done the other way round as well. In any case, one needs to make sure that while going through the introductory chapter, one minimises the chances of letting readers’ attention wander even for a minute or two. By the time it ends, they need to be left curious enough to start their own journey by exploring the book in detail.

We have miles to go before we sleep…

Well, finalising the manuscript is only the first 35% of the story. What follows is a far more arduous journey: getting it produced, marketing and promoting it, and the like.

As Robert Frost says: “The woods are lovely, dark and deep, But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep…”

Related Posts:

The Travails of an Air Passenger

Posted in What ho!, tagged Air Travel, Humour, Obesity, Overcrowding, P G Wodehouse, Travails on September 11, 2025| Leave a Comment »

‘Pig-HOOOOO-OOO-OOO-O-O-ey’: A Sequel

Posted in What ho!, tagged Blandings Castle, Cow Hug Day, Empress of Blandings, George Cyril Wellbeloved, Humour, India, Lady Constance Keeble, Lord Emsworth, P G Wodehouse, Rupert Baxter on August 30, 2025| Leave a Comment »

St. Bernard Dogs: Some Plummy Quotes

Posted in What ho!, tagged Alps, Humour, Italy, P G Wodehouse, St Bernard Dogs, Switzerland on August 21, 2025| Leave a Comment »