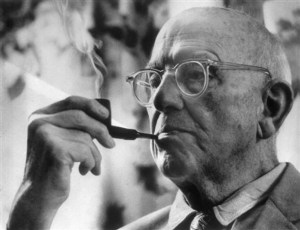

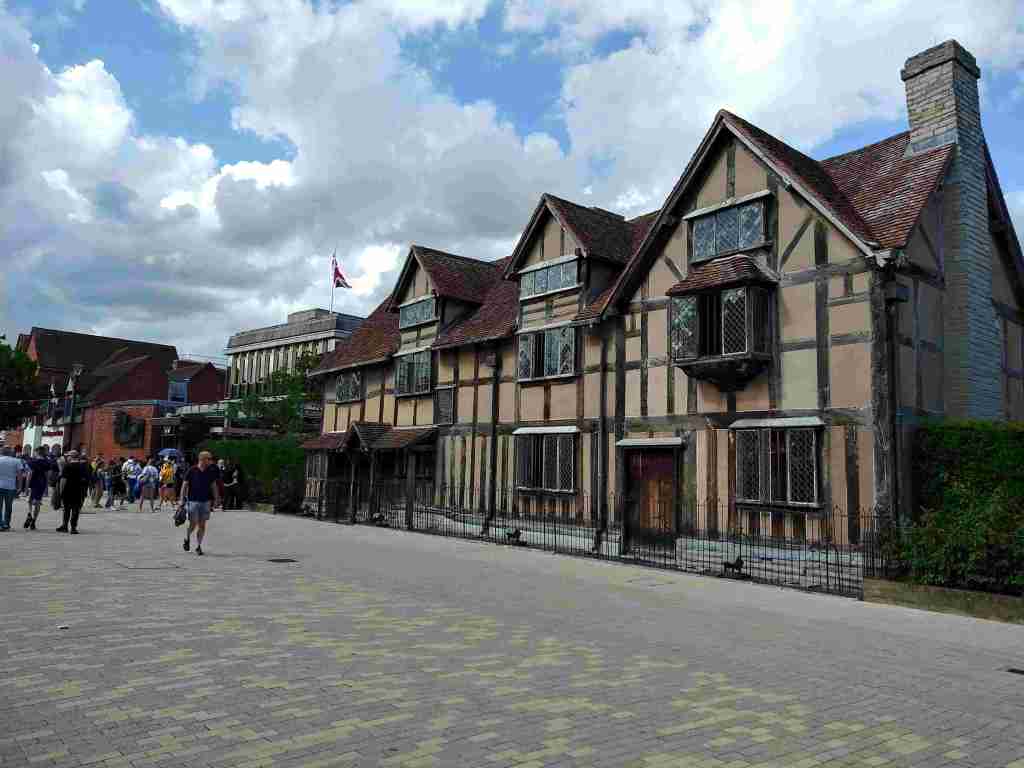

To suggest that P. G. Wodehouse championed the cause of any kind of socialist thought appears, at first glance, wholly implausible, if not mildly absurd. He is the laureate of ethereality, spreading joy, light, and sweetness through his innumerable narratives. He is a painter whose canvas comprises country houses, gentlemen’s clubs, seaside hotels, and film studios. He is the creator of characters who not only amuse and educate but also entertain us. These could be earls with wayward nieces, lordships with unique eccentricities, amiable Drone Club bachelors in doubtful engagements, obdurate aunts, and the occasional lively interloper — be it a alimony-collector, bookie, detective, insurance agent, valet, and village policeman who knows far more than the gentry imagine. Plumsville, his world, is replete with comic complications that restore themselves at the end, more or less as they began. In the bright sunshine of Plum’s subtle humour, quietly incisive wit, could an esoteric concept like social consciousness really exist?

Having devoured and admired his narratives repeatedly over the past few decades, I am often left wondering about this facet of his wordcraft; how delicately he handles questions of power, status, labour, and value. Wherever he does so, it is with kid gloves. Plum is not an in-your-face political analyst. Neither does he advance economic blueprints, nor does he sermonise about statecraft. In many of his narratives, one is apt to notice that there does exist an undercurrent of empathy for the less privileged. Seldom does he showcase the perks of following thoughts steeped in the pristine and rather idealistic stream of socialism. As a Pierre-Auguste Renoir of language, he uses pastel shades of many kinds to present to his readers a pale parabola of social consciousness.

When it comes to exposing the faultlines in the characters of the wealthy, he does not shy away. Most of his stories elevate competence above birth, applauding work that delivers satisfaction, and presenting us with small communities organised less by dominance than by a pally accommodation. Admittedly, these are not the characteristics of conventional political socialism. Instead, he comes out as a champion of egalitarian thought. Underlying most of his narratives is the conviction that title and monetary resources do not necessarily align with merit; that hierarchies can be negated and overcome by intelligence, diplomacy, and an occasional dash of cunning; and that a happy life rests more upon decency and reciprocity than upon accumulation. And if that unveils a streak of social consciousness in his works, it merits a gentle airing.

The Classes as well as the Masses

His admirers as well as critics aver that he concentrates more on the aristocracy and the eccentricities of the upper echelons of British society. However, to be fair to him, he is an author who is concerned not only about the classes but also about the masses. For instance, while Something Fresh takes a detailed look at life below the stairs, Psmith, Journalist dwells at length on the plight of those who live in the Big Apple’s slums, and the courage shown by Psmith to serve them in some way. Elsewhere, romantic alliances take place across the class divide. Or, consider the case of Bertie Wooster, who, we are told, has gone to a school that teaches the aristocracy to fend for itself in case he faces impecunious circumstances (Ring for Jeeves). In narratives like Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen and Plum Pie, denizens protest government policies. In The Inimitable Jeeves, small groups which despise the wealthy and do not mind being seen running around streets with knives dripping with their blood are brought to our notice. Fiery speeches get made, lampooning the idle rich.

I believe Rupert Psmith is the one character created by Plum who could qualify to be alluded to as a socialist in the classical mould. Note his comment on the sartorial choices of a colleague:

Why, Comrade Bristow sneaks off and buys a sort of woollen sunset. I tell you I was shaken. It is the suddenness of that waistcoat which hits you. It’s discouraging, this sort of thing. I try always to think well of my fellow man. As an energetic Socialist, I do my best to see the good that is in him, but it’s hard. Comrade Bristow’s is the most striking argument against the equality of man I’ve ever come across (Psmith in the City).

There are quite a few other characters as well who could be said to be wearing a badge of socialism on their sleeves.

We run into Syd Price (If I Were You), who is a socialist barber. He is part of a mix-up involving the aristocratic Anthony, 5th Earl of Droitwich, with whom he was accidentally swapped at birth. The plot centres on a complicated inheritance scheme involving the two men.

We also get introduced to true-blue socialist politicians who argue against the British military system of ranks in The Swoop! and against the House of Lords in ‘Fate.’

Then we have Miss Trimble in Piccadilly Jim, a “Sogelist” in her clenched-teeth speech; Archibald Mulliner, a temporary Socialist in ‘Archibald and the Masses;’ a newspaper cartoonist referred to in The Small Bachelor; and a Socialistic schoolmistress in ‘Feet of Clay.’

Legislation of a socialistic kind gets decried in ‘Came the Dawn,’ Right Ho, Jeeves, and Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

Here are the main aspects to consider when examining the theme of social consciousness in his works.

A Gentle and Kindly Rebuke to Inherited Authority

Plum’s most enduring proposition is that the upper classes are not fit to rule. In the Jeeves stories, his superior intellect keeps pulling Bertie Wooster and his pals out of the kind of scrapes they keep getting into. The valet’s cool and quiet competence eventually saves the day. The plots may be exquisitely repetitive, but their social meaning is clear. Knowledge, judgement, and sheer common sense come out with flying colours. The psychology of the individual reigns supreme. Birth and inheritance may have conferred upon Bertie a large allowance, a formidable address book, and memberships in exclusive clubs, but he is often perceived as someone who is mentally negligible. If ever he decides to exert his own cerebellum to solve a problem for a pal of his, he ends up tying himself in knots and eventually needs the support of his valet to extricate himself from the mess he creates for himself and those around him. When solutions are needed, they are designed and executed by a professional whose head bulges at the back. We get to realise that each of the narratives is a gentle and kindly rebuke to inherited authority. Plum drives home his point more as a comedy rather than an ideology. The joke lands because we, the readers, instinctively recognise the underlying strains of justice.

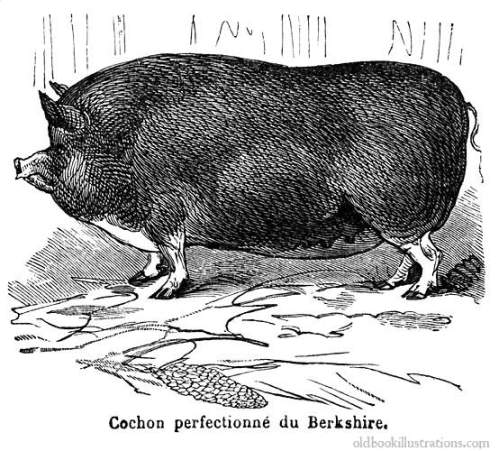

The Blandings series paints the same theme over a broader canvas. Lord Emsworth’s endearing forgetfulness, his obsession with a pumpkin and the Empress of Blandings, and the disruptive behaviour of his relatives form the backdrop against which his suspicious secretaries, moody gardeners, conscientious pig-keepers, unwelcome guests, and impostors of all sizes and shapes keep waltzing in and out. The worth of a person is neither a title nor wealth; it is steadiness of service, the pomp and show with which it gets delivered in a methodical manner, and the gift of getting such things done as locating the master’s glasses or making a newly bought telescope yield satisfactory results. Plum may be merciless when capturing the self-importance of the aimless rich, but never mean-spirited about them as people. His satirical treatment remains humane.

Lord Emsworth might hate visiting London, but respects Gladys and her brother Ern as city-bred insouciant kids reared among the tin cans and cabbage stalks of Drury Lane and Clare Market. They could hurl stones at his Scottish gardener and even stand up to his obdurate sister. When Gladys slips one of her tiny hot hands into his, seeking protection from Angus McAllister advancing at a speed of forty-five miles per hour, he develops a spine of chilled steel. He wishes to be worthy of the lofty standards of employee discipline and servility enforced by his ancestors.

‘This young lady,’ said Lord Emsworth, ‘has my full permission to pick all the flowers she wants, McAllister. If you do not see eye to eye with me in this matter, McAllister, say so and we will discuss what you are going to do about it, McAllister. These gardens, McAllister, belong to me, and if you do not – er – appreciate that fact you will, no doubt, be able to find another employer – ah – more in tune with your views. I value your services highly, McAllister, but I will not be dictated to in my own garden, McAllister. Er – dash it,’ added his lordship, spoiling the whole effect.

One laughs, then one notices the underlying theme touching upon a socialist stream of thought (“Lord Emsworth and the Girl Friend”, Blandings and Elsewhere).

Competence as Moral Capital

Much like Jeeves, there are a host of characters who, whilst brimming with charm, occupy a morally higher ground. They are not only carriers of wisdom, but also more conscientious in the discharge of their duties. These are qualities which their superiors lack. Club stewards, rozzers, head gardeners, secretaries, and nurses reveal their steadfast characters while pushing the plot along. They deliver satisfactory results.

Consider rozzers who invariably refuse nourishment of any kind while on duty. An open display of emotions does not sit well with them. Inwardly, they squirm when told by a Justice of the Peace to lay off someone who violates the law. However, they know when to eat humble pie and quietly follow their orders.

In The Mating Season, Corky loves Esmond but will not marry him until he stands up to his domineering aunts, who disapprove of Corky because she is an actress. When the dog Sam Goldwyn is arrested by Constable Dobbs, Corky, the resourceful owner, charms Gussie Fink-Nottle into extracting him from confinement. Constable Dobbs assumes it was Catsmeat who stole the dog. Since Catsmeat happens to be his fiancée Corky’s brother, Esmond Haddock, a Justice of Peace, decides to assert himself, protect his romantic interests, and make Dobbs drop the case. He points out the slender evidence he has against the alleged accused, while dismissing Dobbs without a stain on his character.

Likewise, in Joy in the Morning, Stilton Cheesewright accuses Bertie of pinching his uniform to be able to participate in a fancy dress ball. Uncle Percy, a Justice of Peace, needs Bertie’s support in standing up to his formidable spouse, Aunt Agatha, to provide an alibi for him to have spent a night away from his living quarters at Steeple Bumpleigh. Uncle Percy refuses to sign the warrant against Bertie. In fact, he goes a step further in ticking off the cop. He laments a despicable spirit creeping into the Force – that of forgetting their sacred obligations and bringing up wild and irresponsible accusations in a selfish desire to secure promotion.

Thus, whereas aristocratic characters are frequently paralysed by pride, a feudal spirit, embarrassment, or romantic affiliations, working professionals act. They take a stand. They take responsibility. On a moral scale, they rank higher than their seniors. In Plumsville, it is their feudal spirit which often saves the day. Their loyalty to their masters scores over the latter’s wealth or inheritance.

Coming back to Blandings Castle, one finds that it takes a bevy of servants to keep things running in an orderly fashion. Below the stairs, we discover a rigid hierarchy, backed by customs and rituals which need to be scrupulously observed. Under the auspices of Mr Beach and Mrs Twemlow, things are always done properly at the Castle, with the right solemnity. There are strict rules of precedence among the servants. A public rebuke from the butler is the worst fate that can befall a defaulting member of this tribe.

When it comes to passing judgement on the state of affairs in society, they have their own mind. For example, when the matter of breach of promise cases comes up, Beach holds the following view:

And in any case, Miss Simpson,” he said solemnly, “with things come to the pass they have come to, and the juries–drawn from the lower classes–in the nasty mood they’re in, it don’t seem hardly necessary in these affairs for there to have been any definite promise of marriage. What with all this socialism rampant, they seem so happy at the idea of being able to do one of us an injury that they give heavy damages without it. A few ardent expressions, and that’s enough for them. You recollect the Havant case, and when young Lord Mount Anville was sued? What it comes to is that anarchy is getting the upper hand, and the lower classes are getting above themselves. It’s all these here cheap newspapers that does it. They tempt the lower classes to get above themselves (Something Fresh).

Plum’s narratives have a clear undercurrent: down the stairs for genuine perspiration and up the stairs for feigned inspiration. This scheme of things debunks the notion that hierarchies are justified by birth.

Comrade Psmith and the Whiff of Reform

In Psmith, Journalist, the monthly journal Cosy Moments undergoes a transformation when the suave and unflappable Rupert Psmith takes over as a voluntary subeditor. Cosy Moments is a journal for the home. It is the sort of paper which the father is expected to take home from his office and read aloud to the kids at bedtime. Its circulation is nothing to write home about. Psmith suggests a different strategy. He outlines his vision for the magazine thus:

Cosy Moments should become red-hot stuff. I could wish its tone to be such that the public will wonder why we do not print it on asbestos. We must chronicle all the live events of the day, murders, fires, and the like in a manner which will make our readers’ spines thrill. Above all, we must be the guardians of the People’s rights. We must be a search-light, showing up the dark spot in the souls of those who would endeavour in any way to do the PEOPLE in the eye. We must detect the wrong-doer, and deliver him such a series of resentful buffs that he will abandon his little games and become a model citizen.

Eventually, Psmith decides to help impecunious dwellers of poorly maintained tenements. He ends up dealing with New York’s slum landlords and crooked bosses. The tone of the narrative is airy, but the targets are not. Psmith uses Cosy Moments, the magazine he runs, to expose exploitation, cheer on reform, and defend the powerless. The satire in this narrative is not merely of the weak points in his adversaries, which he exploits with aplomb; it is of systemic injustice. Plum does not allow the narrative to curdle into earnestness, yet he reveals an unmistakable sympathy for the urban poor and a hatred of the sharp practice of those who profit from misery.

Likewise, Psmith in the City gives us a ringside view of the soul-tormenting processes of routine banking, highlighting the underlying spiritual drudgery. Rigid procedures rule, so does hierarchy. One experiences soul-deadening routine, petty tyrannies, the suffocation of youthful promise by a gigantic machine that puts a premium on conformity over talent. Tea breaks and lunch breaks are the only occasions which break the monotony. In any case, the atmosphere chimes with a wider early twentieth-century suspicion of bureaucratised capitalism. Plum can be imagined to be more amused than angry, but he is not insensitive.

Flirtations with the Left

A highly diluted version of what political purists might mistakenly allude to as socialism not only appears occasionally but is also an integral part of Plum’s cultural landscape. It is not an alien menace which deserves to be despised and discarded outright. Plum treats it as a place where excitable but good-hearted people congregate, make speeches, even if under the transient spell cast upon them by the party of the other part. He does flirt with the Left, though his trademark subtle humour arises from a kind of recognition: the Left is not monstrous, merely dramatic, and susceptible to the same follies as everyone else.

There are also moments when Plum plays directly with socialist imagery.

Bertie Wooster always seems to stumble into chaos, and protests are no exception. One day, he gets stuck in a London traffic snarl caused by an angry crowd, only to spot his former fiancée, Vanessa Cook, leading the march (Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen).

His friend Bingo Little is not much different — he once grew a beard and joined a radical group just to impress a fiery revolutionary, even going as far as to insult Bertie as an idler, a non-producer, a prowler, a trifler, and a bloodsucker. Bingo even goes on to call out his own uncle Lord Bittlesham in a speech:

And the fat one!” proceeded the chappie. “Don’t miss him. Do you know who that is? That’s Lord Bittlesham! One of the worst. What has he ever done except eat four square meals a day? His god is his belly, and he sacrifices burnt-offerings to it till his eyes bubble. If you opened that man now you would find enough lunch to support ten working-class families for a week,” he claims (‘Comrade Bingo’, The Inimitable Jeeves).

Later, while working as an editor of Wee Tots, Bingo gets dragged into another protest by a red-haired girl named Mabel, who sits down in Trafalgar Square to make headlines for her anti-bomb campaign. Bingo reluctantly joins her, gets arrested, lands in the papers, and ends up in trouble with his wife — though, as always, things somehow work out in the end (‘Bingo Bans the Bomb’, Plum Pie).

Of Hollywood, Movie and Publishing Moguls

Plum’s forays into Hollywood and publishing are perhaps among his sharpest class critiques. His narratives dispel the mystique of aristocracy associated with them and often bring into focus the raw power of capital. Megalomaniac studio bosses, slick agents, and moguls obsessed with formulas for profit become his new earls and aunts.

When a fluffy-minded Lord Emsworth pockets a fork at the Senior Conservative Club, Adams happens to check him. Aunt Dahlia may threaten to ban Bertie from her dining table, which offers lavish spreads by Anatole, if he does not do her bidding.

Likewise, an aspiring wannabe heroine Vera Prebble proves to have better negotiating skills when she outwits three studio chiefs and secures her future as a movie star. Their weakness? Well, they desperately need liquor during prohibition days for a party they are hosting at one of their places. Lord Tilbury keeps missing his former star editor, Percy Pilbeam, whose seedy society gossip had ensured soaring business for Society Spice, one of the journals published by the Mammoth Publishing Company (‘The Rise of Minna Nordstrom’, Blandings Castle and Elsewhere; Frozen Assets).

To his credit, he honours craft and talent above everything else – the proficient writer, the adaptable actor, the competent fixer. Again, his target is not wealth per se, but the worship of money as the sole metric of value. When a character is reduced to a “nodder”, whose primary role is to agree with the boss, Plum is presenting to us an organisational pathology that corrodes judgement and humiliates labour (‘The Nodder’, Blandings Castle and Elsewhere).

In no way does his approach differ much from the one he adopts in Psmith in the City (Chapter 21), while introducing us to the concept of a “mistake-clerk” whose duty it is to get squarely blamed when a fuming customer trots in to register a complaint. He is hauled into the presence of the foaming customer, cursed, and sacked. The bank gets a satisfied customer. The mistake-clerk, if the showdown has indeed been traumatic, promptly applies for a jump in his salary.

One might as well consider this to be a notably democratic instinct. Plum sides with people who take pride in their work and who want to be treated as grown-ups. He lampoons gigantic corporate machines, which often treat their most crucial asset – the people – as mere nuts and bolts. His works highlight an ethical respect for the dignity of labour.

Money, Inheritance, and the Comedy of Redistribution

It is amazing to see how often Plum’s plots are driven by inheritances, allowances, trust funds, and the conditions attached to them. In Plumsville, money has high viscosity. It moves, albeit hesitantly. It is socially consequential. It shapes marriages, motivates impostures, and invites moral tests. Fortunes are threatened, allowances are cut, dowries are reconsidered; pearls, pigs, and even French cooks who happen to be “God’s gift to our gastric juices” can function as mobile capital that could reshape relationships. The whole scheme is designed to behave like a comic model of redistribution, orchestrated by Jeeves-like planners who understand how to reallocate resources so that the largest number of people can chug along in their lives with ease.

It is tempting to over-emphasise this. Plum’s interest in money is not economic but only theatrical. His narratives invariably tie money to emotional well-being and social status, thereby demystifying it. Even death becomes a cause for celebration, often conferring wealth and social status upon the inheritors. Money is not portrayed as a demon. It is merely presented as a tool that can be used to produce human flourishing or human misery, depending on the wisdom of those who control it. Thus, he chooses to write about wealth in a deeply mature way. It is sympathetic to a social democratic ethic that treats the economy as a servant of life rather than its master. Perhaps Plum indirectly nudges us to live our lives while remaining somewhat detached from wealth, worldly possessions, titles, fame, and all other trappings of power and pelf – things which are essentially transient in nature.

Of Alliances across the Social Divide

When it comes to Cupid’s machinations, age, caste, creed, profession, and social status do not really matter. Even time ceases to matter. Love may remain dormant for a long time but can get revived in a moment – much like Psyche getting revived by Cupid’s kiss!

Uncle George’s plans to saunter down the aisle with a girl from the lower middle classes face a serious glitch – that of a stout disapproval from Aunt Agatha. After all, family honour is at stake. She promptly gives a blank cheque to Bertie, who is expected to rally around and pay off the girl to secure a ‘release’ for Uncle George.

The family remembers that years ago, long before this uncle came into the title, he had had a dash at a romantic alliance. The woman in question at that time had been a barmaid at the Criterion. Her name was Maudie. To her went the credit of addressing Uncle George as Piggy. He loved her dearly, but the family would brook no such nonsense. Eventually, she was paid off and the family honour protected.

It transpires that Maudie happens to be the aunt of the girl who appears to have cast a spell over Piggy in the present situation. When Piggy and Maudie come face-to-face after many years, the chemistry between them is found to be intact. Admittedly, time has extracted its toll. Concerns about the lining of the stomach end up acting as a catalyst to bring the two souls together (‘Indian Summer of an Uncle’, Very Good, Jeeves!).

A similar theme unfolds in the matter of Joe Danby and Bertie’s Aunt Julia Mannering-Phipps (‘Extricating Young Gussie’, The Man with Two Left Feet).

Bingo Little depends on his uncle, Mr Mortimer Little, for an allowance, and fears Mr Little will not approve of Bingo marrying a waitress. By way of a solution, Jeeves suggests books by the romance novelist Rosie M. Banks, which portray inter-class marriage as not only possible but noble. Bertie tells Mr Little that Bingo wants to marry a waitress, and Mr Little, moved by the books, approves. When Bertie asks him to raise Bingo’s allowance, however, Mr Little refuses, saying it would not be fair to the woman he soon intends to marry, his cook, Miss Watson (‘No Wedding Bells for Bingo’, The Inimitable Jeeves).

George Bevan’s friend and colleague Billie Dore, a chorus girl, visits Belpher Castle and bonds with Lord Marshmoreton over their shared love of roses. Eventually, Lord Marshmoreton and Billie get married, whereas his daughter, Lady Patricia Maud Marsh, agrees to walk down the aisle with George Bevan (A Damsel in Distress).

In Frozen Assets, Gwendoline Gibbs is secretary to Gerald ‘Jerry’ Shoesmith’s formidable employer, Lord Tilbury, who owns and runs the Mammoth Publishing Company. She saves his employer from many an embarrassing situation, and the two get engaged.

Through all these narratives, Plum goes on to assert the precedence of the emotion of love over such social considerations as one’s socio-economic status in life and the class to which one belongs. Enter Cupid, and class differences simply melt away. A long-forgotten relationship might get revived, with the lining of the stomach playing the role of a catalyst. An alliance could also be formed based on the fulfilment of a basic need. In any case, there is a limit to which a family can attempt to maintain the purity of its so-called blue blood and protect its genealogy. Here again, Plum highlights the importance of embracing the concept of a society built on egalitarian values and norms.

The Village and Its Ethical Ecosystem

Much of Plum’s comedy unfolds in rural or semi-rural settings where custom and negotiation score over sheer coercion. Village fêtes, church halls, conduct of local constables, and family retainers create an ecosystem of mutual respect and recognition. Debts of honour matter. Kindnesses are remembered with gratitude. A spirit of quid pro quo prevails. The law, when it appears, is comically lenient. The wheels of justice do move, though not always along predictable lines.

For instance, in The Girl in Blue, when Chippendale, a butler, gets in trouble with a cop for using his bicycle to teach a girl to ride, his employer refuses to help. Feeling stuck, Chippendale sulks — until Barney Clayborne, a lady he knows, steps in, and pushes the cop into a brook where he usually cools his feet at the end of a day. The cop decides to drop the complaint.

Magistrates, such as the one at the Vinton Street police court (Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit), often portray the less lovable qualities of a senior officer of the Spanish Inquisition. However, considering Bertie’s youth, he shows leniency. Instead of a long stretch in the chokey, he merely slaps a fine of ten pounds for having assaulted an officer of the law and obstructing him in his duties. Justice feels more like restoration than retribution. Problems are solved by dialogue, apology, and by clever offers of mundane incentives, which make life smoother.

Human values prevail. So does the milk of human kindness. A treatment of this kind proves to be a soothing balm for our wounded souls, endearing Plum to all those who come across his narratives.

Characters in Plumsville frequently rely on each other for support and assistance, regardless of their social standing. This theme can be seen as a nod to the idea of collective effort and mutual aid, which are central to the concept of a society which has a conscience that is alive and kicking.

Here again, Plum does not offer a manifesto. Rather, the basic premise is that people have an innate goodness in them, are willing to improve themselves, and that communities can be steered better by humour, patience, and good sense. Plum’s tendency to showcase social life as a web of relationships, not an arena of domination, is deeply compatible with the communitarian strand of the British way of life. It puts a premium on collaboration over competition, preferring reconciliation to victory.

A Stark Difference in Upbringing

Plum says that one of the compensations life offers to those whom it has handled roughly is that they can take a jaundiced view of the petty troubles of the sheltered. He posits that just like beauty, trouble is in the eyes of the beholder. Aline Peters, the daughter of an American millionaire, may not be able to endure with fortitude the loss of even a brooch, whereas Joan Valentine, who is forever struggling to keep the wolf away from her door, must cope with situations which often mean the difference between having just enough to eat or starving. For the reward of a thousand pounds, Joan finds it worth her while to accompany Aline to Blandings Castle as a lady’s maid.

This is Plum’s subtle way of heightening our level of awareness about the contrast between the haves and the have-nots of society. We realise the stark difference between the upbringings of Peters and Valentine. It is not difficult to fathom why their attitudes towards life are distinct (Something Fresh).

A Libertarian Temperament

There is one major caveat. Plum despised sectarianism of any kind. In Roderick Spode, he presents to us the immortal profile of a would-be dictator in black shorts. However, what he presents to us is not an argument for any kind of socialism – whether of a stiff-upper-lip kind or a super-soft version of it. Instead, it is a cautionary message against handing power over to people with swollen heads and shrunken hearts. Instinctively, he distrusts those who consider human beings as personal chattel and follow the use-and-throw practice popularised by the corporate world. If one takes socialism to mean a politics of doctrinal certainty, Plum offers nothing of the kind. His temperament is essentially libertarian. He wishes people to be left alone to grope their way towards their personal vision of happiness. If one rules over them, one does it by being compassionate and by introducing measures and policies which enable them to live more contented lives.

It is easy to see that his fiction aligns more naturally with an egalitarian ecosystem than with a hierarchical one. He lampoons the eccentricities and vulnerabilities of the privileged but celebrates the intelligence and perseverance of workers. He proposes that real satisfaction can be derived in the doing, not the owning. His narratives paint a world in which social peace is built by courtesy, patience, and practical knowledge, not by authoritative decrees. These are the building blocks of a humane and even-handed society.

His brand of socialism is not so in a doctrinal sense. However, the depiction of his characters and the way they handle challenges coming their way rhymes well with the core ideology.

The Innate Goodness of Homo sapiens

Plum refuses to sneer. Nor is he a champion of the underdogs. Adams, the head steward at the Senior Conservative Club, is quick to identify Lord Emsworth when he comes in for a spot of lunch. Plum paints a positive picture of the man when he says that:

It was Adams’ mission in life to flit to and fro, hauling would-be lunchers to their destinations, as a St. Bernard dog hauls travellers out of Alpine snowdrifts.

Having finished his lunch, Lord Emsworth leaves Adam in a euphoric state of mind. After all, on that day, he had found the Lord in full form when it came to his absent-mindedness. He is imagining the newfound jokes he can narrate to his wife and to the guests that evening while entertaining them at his lair (Something Fresh).

Even his roguish characters are handled with a delicacy that suggests an underlying belief that they have the potential to do better tomorrow. He does not compartmentalise people into categories. He captures detail, cultivates sympathy, and prizes forgiveness. In the end, his comedy’s most persistent message is that people – all sorts of people – can be nudged gently towards right action.

Plum wants us to develop the capacity to laugh at our errors and to imagine our way back into a community of like-minded people.

What Plum is Not

It would be improper and unkind to label Plum as a writer in the same league as, say, George Bernard Shaw or George Orwell. The political economy, the state, or the machinery of welfare do not attract his attention. He is comfortable writing about small groups where affection and ingenuity can solve problems without recourse to law or revolution. Nowhere does he present labour as collective action. Instead, he puts a premium on the agency of gifted individuals. The concluding scenarios in his narratives typically restore the social order, albeit with some improvements. If there is redistribution, it is along ethical lines before it is material: people learn a lesson, they apologise, and they decide to reform themselves.

He is, however, allergic to arrogance and pretension, sensitive to exploitation, and appreciates the dignity of competence wherever it appears. The milk of human kindness courses through the veins of most of his characters. It is surely not socialism in a doctrinal sense, but it resonates well with the core ideology.

Why the Question Matters

Many a time I get asked as to why one should bother about the presence of social consciousness in Plum’s works. I believe that humour is one of culture’s stealthiest instructors. When combined with a dash of wit and wisdom, it softens the rigidity inherent in hierarchies. It also goes on to celebrate the triumph of skill over status. Even before one may argue, it helps readers instinctively realise that a just society is one in which intelligence, patience, and a tendency to help others prevail over swagger and birthright. Here is something profound Plum says about happiness:

As we grow older and realise more clearly the limitations of human happiness, we come to see that the only real and abiding pleasure in life is to give pleasure to other people.

Like many other truths of life embedded in his narratives, Plum imparts similar lessons effectively. A reader who has learned to appreciate the quiet brilliance of a valet has already taken one step away from worshipping one’s inheritance.

Results for the Greater Good

Such lessons could find a final resonance here for leaders of any persuasion. Plum repeatedly demonstrates that leadership is service delivered to obtain results which are meant not for individual gain but for the greater good. Of course, this involves deep preparation, genuine care for human foibles, and a bias for solutions that allow everyone to save face. If one is looking for a parable of humane, non-authoritarian authority, Jeeves comes through as a prime example. He listens. He observes. His cunning knows no bounds. Using intelligence, tact, and resource, he designs paths through challenging circumstances that leave communities in a happy state of mind. To put it simply, he delivers satisfaction. His character represents a vision that fits well into the gentler aspirations of an ethical society and the broader ideals of a conscious, empathetic, and collaborative civic life.

The undercurrent of social conscience which runs across the oeuvre of Plum is a facet of his works that deserves to be explored and popularised further, to sensitise people to the benefits which could accrue to everyone. In his inimitable style, he gently raises our level of social consciousness. He does so by satirising privilege, showcasing competence as moral capital, demonstrating how a journal could be used as a means to bring about social reform, occasionally flirting with the left, giving us a peek into the world of movie and publishing moguls, presenting to us a comedy of redistribution of wealth, forging alliances between the classes and the masses, delineating the rural ethical ecosystem, and highlighting the stark differences in our attitude towards life based on our upbringing. Such are the hues that comprise the pale parabola of social conscience dished out by him.

Towards a Softer Egalitarianism

One may well ask if Plum has a socialist streak. Not in the sense that would satisfy either a politician or a political scientist. However, when it comes to gut instincts, his comic universe is indeed egalitarian. He dissolves the mystical aura of privilege, redistributes honour to those who earn it, and imagines communities patched together by kindness and craft rather than command. The politics is sotto voce, but the music is audible. If one listens carefully, amid the musical laughter, latent are many a whisper: people matter more than positions, competence outranks pedigree, and the best societies are those in which everyone, whatever their station, is allowed to be intelligently, decently useful.

Call it a social consciousness if you like; call it, perhaps more accurately, either a civilised sense of fairness or a conscious way to live our lives. Either way, the pale parabola is there, peeping through his narratives, much like diffused sunlight descending upon Blandings Castle, gently lighting up its ivied walls, its rolling parks and gardens, its moss-covered Yew Alley, lake, outhouses, its inhabitants, and, of course, the Empress’ den.

Reference

‘If I Were You — Annotated’, Madame Eulalie: The Annotated P. G. Wodehouse, available at: https://madameulalie.org/annots/pgwbooks/pgwiiwy1.html#socialist

Notes

- Inputs from Tony Ring and Neil Midkiff are gratefully acknowledged.

- Likewise, support received from Dominique Conterno, Co-founder of Conscious Enterprises Network (https://www.consciousenterprises.net)

Related Posts