Introduction

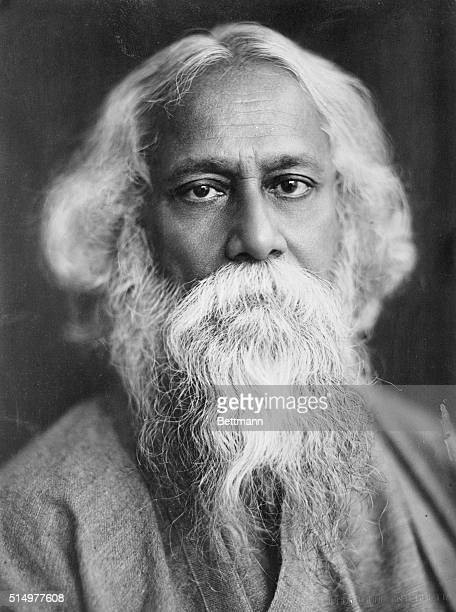

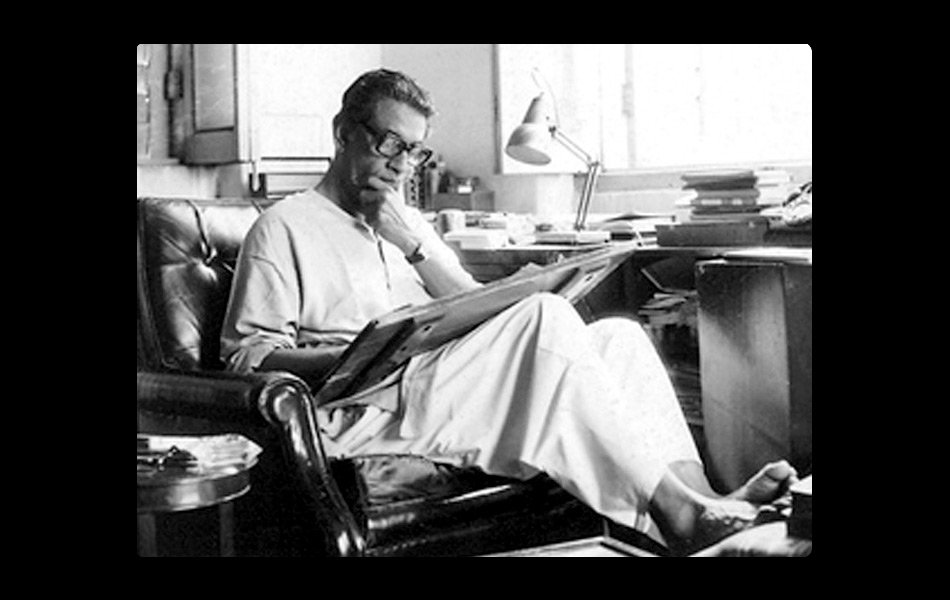

As the sombre mist of mortality settles upon the world, I find myself, along with countless others, lost in the labyrinth of thought, pondering the enigmatic fate that had beckoned the great poet, Rabindranath Tagore, to the realm of the eternal, on the 7th of August, 1941. For the 83rd time, we are forced to confront the stark reality of his passing, and the weight of his absence settles upon our collective conscience like a shroud. And yet, as we gaze upon the canvas of his extraordinary life, we cannot help but wonder what wondrous tapestry of words and ideas the Bard of India might have woven had he remained among us, a tantalizing what-if that haunts us like a persistent melody.

Looking back to early days

As a child of tender years, his idealistic nature found expression in a paean to the raindrops’ embrace upon leaves, their gentle patter evoking the rhythmic swaying of an elephantine behemoth –

“Water pours, leaves dance,

Crazy elephant’s head sways in a trance“

To attempt to encapsulate his colossal contribution to the arts would be like trying to capture the sun in a teacup. Like a literary Gargantua, he devoured every realm of culture, leaving behind a Gargantuan feast of creative output.

His ‘Nobel’ contribution

The year 1913 was a moment in the annals of literary history when the world finally awakened to the profound significance of Rabindranath Tagore’s contributions to world literature. It was as if the veil of ignorance had been lifted, and the international community beheld, with a mixture of wonder and reverence, the sheer brilliance of the Bengali bard’s thoughts. And we, as Indians, were filled with a sense of pride, nay, a deep-seated sense of ownership, for it was our own Tagore who had been instrumental in illuminating the path of human understanding.

It is worth noting that Tagore himself had taken the initiative to translate his creation, ‘Gitanjali’, into the English language, thereby rendering his exquisite and sensitive verse accessible to a global audience. The response was nothing short of astonishing, as the world was left agog at the beauty and profundity of his poetry. And it was none other than Thomas Sturge Moore, that erudite British poet, author, and artist, who had the foresight to recommend Tagore’s name for the Nobel Prize, even before the year 1913 had dawned.

Tagore in Bollywood

However, in this discourse, our attention shall be directed solely to the instances wherein the cinematic artisans of Bollywood have sought to translate the essence of his creations into the vibrant medium of visual storytelling. It is not easy to capture the nuances of a work of a literary kind in the medium of moving images. As we shall see, while some movie directors have done it very diligently, others have taken a few liberties with the original narrative. Nevertheless, let us consider some such endeavours where his words have found expression on the silver screen, making them reach out to a much wider audience.

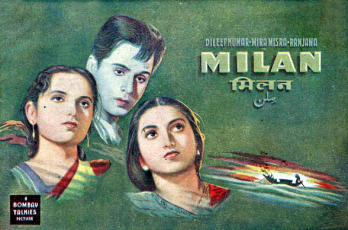

Milan (1946)

Adapted Story: Noukadubi (The boat wreck)

Director: Nitin Bose

Cast: Dilip Kumar, Mira Misra, Ranjana, Moni Chatterjee, S. Nazeer

Synopsis: In the arcane tapestry of 1905 Calcutta, a city pulsating with intellectual fervour, Ramesh, our cogent protagonist, becomes ensnared in a labyrinth of societal dogma and the yearnings of the heart.

Dilip Kumar imbues Ramesh, a fledgling law student, with a palpable yearning for Hemnalini, portrayed by the enigmatic Ranjana. However, their burgeoning romance is stymied by the machinations of Akshay, menacingly brought to life by Pahari Sanyal, thus weaving a thread of intrigue into the narrative.

As the relentless tendrils of fate interlock, familial duty and the dictates of the heart collide. Ramesh is summoned back to his ancestral village, setting in motion a whirlwind of events characterized by mistaken identities and emotional tempests. Amidst this turmoil, Ramesh’s virtuous aspirations are put to the test as he grapples with the precarious equilibrium between obligation and amour, a timeless theme in the grand theatre of life.

Upon his return to Calcutta, Ramesh’s noble efforts to enlighten Kamala, his unanticipated bride, lend an intricate layer to the unfolding tale. The reverberations of Ramesh’s clandestine union resonate throughout the hallowed halls of society, threatening to shatter his impending marriage to Hemnalini.

As tensions escalate to a fever pitch, the stage is set for a grand denouement, wherein truths are elucidated, hearts are mended, and love emerges victorious, transcending the constraints of adversity.

The Music: Verily, the musical composition of this cinematic endeavour was undertaken by the esteemed Anil Biswas. The lyrics, crafted with utmost precision and elegance, sprang forth from the minds of the renowned Pyare Lal Santoshi and Arzu Lakhnavi.

Parul Ghosh, a vocal virtuoso who lent her dulcet tones to a significant portion of the filmic arias, shared a familial bond with Anil Biswas, being his sibling of less advanced years. Historia attests to her as one of the inaugural exemplars of that novel method of sonic preservation known as playback singing within our realm of cinematic entertainment.

Geeta Dutt, another vocalist of exceptional talent, graced the film with her mellifluous contributions.

Trivia: In a spirit of dialectical inquiry, it is imperative to elucidate that the cinematic narrative of this film emanated from the pen of Sajanikanta Das, editor of Shanibarer Chithi (Saturday’s Letter). Das, a man possessed of a keen intellect and a mordant wit, had previously directed his critical gaze upon the esteemed Rabindranath Tagore. With a discerning eye, he had dissected Tagore’s literary aesthetics and his profound societal influence, finding them wanting.

Ghunghat (1960)

Adapted Story: Noukadubi (The boat wreck)

Director: Ramanand Sagar

Cast: Bharat Bhushan, Pradeep Kumar, Bina Rai, Asha Parekh

Synopsis: In a tale akin to Milan’s classic narrative, the annals of modernity unveil a poignant drama. A young man, Ravi, faces an agonizing dilemma when his parents demand that he sever his affection for Laxmi and marry another. With a heavy heart, he acquiesces to their wishes.

As fate would have it, a fateful train journey brings together a group of newlyweds, including Ravi and his bride. Tragedy strikes and the train is engulfed in a catastrophic accident. Ravi awakens to find an unconscious bride lying beside him. Mistaking her for his own wife, he transports her to his abode.

Upon realizing the demise of his true wife, Ravi is horrified to discover that the bride he has brought home is a different lady named Parvati. Tormented by guilt and compassion, he embarks on a desperate search for her husband, Gopal.

Unbeknownst to Ravi, Parvati had already stumbled upon the truth and made her escape. Seeking solace, she wandered aimlessly until she fell into the river Jamuna. Her fate led her to the doorstep of Gopal’s residence, where she encountered his brother, Manohar, who had lost his eyesight in the accident.

Torn between her newfound duty to care for Manohar and her longing to reunite with Gopal, Parvati remained silent about her true identity. A web of secrets and unspoken truths now intertwined their lives, leaving them adrift in a sea of uncertainty.

Music: The renowned music maestro Ravi brought forth the essence of Shakeel Badayuni’s exquisite lyrics on the silver screen. The ten melodious compositions were rendered by such legendary artists such as Mohd. Rafi, Asha Bhosle, Lata Mangeshkar, and Mahendra Kapoor. Among these, stand-out gems like Lata Mangeshkar’s rendition of ‘Lage Na Mora Jiya’, Mohd. Rafi’s soulful ‘Insan Ki Majbooriyan’, Asha Bhosle’s enchanting ‘Gori Ghunghat Mein’, and the mesmerizing duet of Mahendra Kapoor and Asha Bhosle in ‘Kya Kya Nazaray Dikhati Hai Ankhiyan’.

Kabuliwala (1961)

Adapted Story: Kabuliwala

Director: Hemen Gupta

Cast: Balraj Sahni, Sonu, Usha Kiran

Synopsis: In the realm of human narratives, we encounter a departure from convention—a tale in which the traditional roles of “boy” and “girl” are defined differently, “boy,” an elderly gentleman, finds himself interacting with a diminutive “girl” of five years of age, reminiscent of the incongruous coupling in P.G. Wodehouse’s “Lord Emsworth and Girlfriend.” However, this narrative possesses a distinctiveness that renders it a tale wholly its own.

Rahamat, a peripatetic merchant from Afghanistan, ventures to India seeking to peddle his wares. Here, he makes the acquaintance of Mini, a young lady of tender years. As their interactions deepen, a profound bond forms between them, akin to that of a father and daughter. Rahamat, reminded of his own daughter of Mini’s age, finds his paternal instincts stirring.

Circumstances conspire against them, and Rahamat is unjustly incarcerated. Upon his release, he seeks to reunite with Mini, unaware that the passage of time has wrought a significant change in her appearance. Mini, now a young woman, has no recollection of her former companion.

Grief-stricken, Rahamat departs India with a forlorn hope that his lost daughter may yet recognize him upon his return. Such is the nature of this enigmatic tale, where love and longing collide in a poignant exploration of the complexities of human relationships.

Music: Salil Choudhury, a veritable polymath, has bestowed upon us an ethereal symphony that perfectly encapsulates the narrative upon which it rests. In my humble estimation, there is no individual more adept at translating the Bengali soul into the universal language of music than this esteemed composer.

Furthermore, the illustrious voices of Hemant Kumar, Mohd. Rafi, Manna Dey, and Usha Mangeshkar serve as veritable conduits for the emotive lyrics penned by Prem Dhawan and Gulzar. Their vocal artistry transcends the realm of mere performance, becoming an integral thread in the tapestry of this cinematic masterpiece. Personally speaking, the “Ganga” song by Hemant Kumar is my all-time favourite!

Trivia: The Bengali iteration of the film was helmed by Tapan Sinha, a cinematic visionary whose repertoire extended beyond the hallowed borders of our country. His masterful direction of such seminal works as “Sagina” and “Zindagi Zindagi” has indelibly etched his name in the annals of cinematic history. To this humble observer, his unparalleled versatility renders him the paramount cinematic luminary of our times.

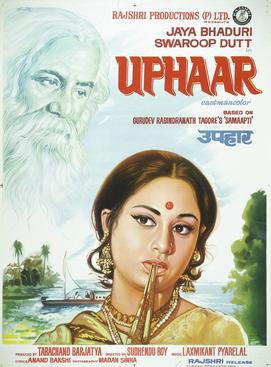

Uphaar (1971)

Adapted Story: Samapti (The Ending)

Director: Sudhendu Roy

Cast: Swarup Dutta, Jaya Bhaduri, Suresh Chatwal, Nandita Thakur

Synopsis: The eternal entanglements of the human heart! In the sweltering metropolis of Calcutta, a most intriguing tale of love, duty, and, dare I say, a pinch of mayhem unfolds. Our protagonist, Anoop, a law student with a mind as sharp as a razor, finds himself ensnared in the time-honoured tradition of arranged matrimony. His widowed mother, no doubt with the best of intentions, sets her sights on the lovely Vidya, a neighbour with a face as fresh as the morning dew.

But, alas, fate has a way of playing the mischief-maker. Upon making the acquaintance of Vidya, Anoop’s heart is suddenly hijacked by none other than Minoo, a rustic beauty from the village, with a smile that could charm the birds from the trees. In a most unbecoming display of defiance, Anoop defies his mother’s carefully laid plans and instead takes Minoo as his bride.

Now, it’s not long before the newlyweds discover that Minoo’s domestic skills are, shall we say, somewhat lacking. The poor dear can’t boil water to save her life, and Anoop’s mother, God bless her, is left to wonder if she’s made a grave mistake in letting her son marry this…this…Minoo.

The inevitable friction ensues, and Anoop, in a fit of exasperation, absconds to Calcutta, leaving Minoo to her own devices. But, as the days turn into weeks, Minoo’s love for Anoop begins to simmer, like a potent curry left to stew. She takes it upon herself to pen a heartfelt letter, a cri de coeur, if you will, only to have it met with deafening silence.

Still, undeterred by the setbacks, Minoo’s love for Anoop remains unwavering, a beacon of hope in the midst of marital turmoil. And it is at Anoop’s sister’s humble abode in Calcutta, a veritable haven of familial warmth, that the star-crossed lovers finally reunite, their love stronger and more resilient than ever.

As I see it, Minoo’s carefree spirit and boyish charm evoke the irrepressible Maria of ‘The Sound of Music’, yet whereas Maria had the solace of the Mother Superior at the Abbey who grasped the essence of her personality and encouraged her to ‘Climb every mountain…’, Minoo wandered, unguided, misunderstood and alone. It’s a difference that strikes a poignant chord.

Music: As I recall, the melodies that wafted through the evening air were the handiwork of the esteemed duo, Laxmikant Pyarelal, whose mastery of the musical arts is renowned far and wide. And, it was the legendary vocal triumvirate of Mohd. Rafi, Lata Mangeshkar, and Mukesh who lent their golden voices to the proceedings, imbuing the entire affair with a sense of grandeur and elegance.

Trivia: In 1971, this movie was chosen to represent India at the Academy Awards, but it did not get nominated. Later, it was dubbed into different South Indian languages, becoming successful in Malayalam as “Upaharam” in 1972. “Samapti” was originally a Bengali movie directed by Satyajit Ray and is one of three short films based on stories by Tagore, released together as “Teen Kanya.”

Geet Gata Chal (1975)

Adapted Story: Atithi (The Guest)

Director: Hiren Nag

Cast: Sachin, Sarika, Khyati, Urmila Bhatt

Synopsis: Durga Babu and his wife, Ganga, found themselves in the presence of Shyam, a lad possessing a talent for singing and dancing that was nothing short of extraordinary. Touched by his plight as an orphan, they extended a warm invitation to him to take up residence within their abode. As Shyam gradually assimilated into the daily routine of the household, a strong friendship blossomed between him and their daughter, Radha.

Little did Shyam realize, but Radha’s fondness for him extended beyond the boundaries of mere companionship. However, his feelings for her remained rooted in the soil of camaraderie. Shyam, with a heart yearning for the open road and unbridled liberty, recoiled at the very idea of settling down. When he caught wind of the family’s designs to wed him off, he felt a sense of confinement akin to that of a bird ensnared within a cage. In a dramatic turn of events, he made a swift getaway, leaving behind a heartbroken Radha.

The question lingers in the air like the scent of a freshly baked pie – will Shyam ever uncover his path back to the homestead? And what tumultuous repercussions will this sudden departure have upon the delicate balance of domestic relationships within the family?

Music: The music was scored by Ravindra Jain and Kishore Kumar, Mohd. Rafi, Aarti Mukherjee lent their voices.

Trivia: This cinematic tale too was brought to life in the Bengali language from literary origins by Tapan Sinha who had a discussion with Satyajit Ray about how to portray the ending of the story on-screen for an international audience. The original tale concludes with Tarapada leaving the mansion just before his marriage, abandoning his would-be wife. However, in a bid to conclude the story differently, Tapan Sinha depicted the bride-to-be weeping over the lost marriage. Satyajit Ray, sensing this wouldn’t resonate with international audiences, insisted on sticking to the original storyline of the protagonist vanishing. In contrast, the Hindi film adaptation opted for a happy ending, reuniting Shyam and Radha.

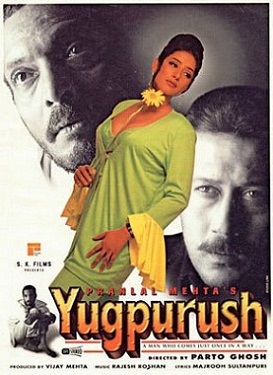

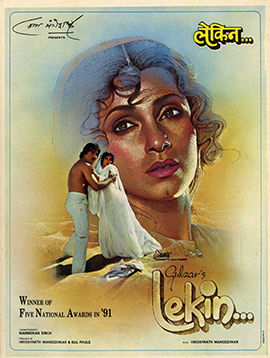

Lekin (1991)

Adapted Story: Kshudhita Pashaan (The Hungry Stones)

Director: Gulzar

Cast: Vinod Khanna, Dimple Kapadia, Amjad Khan, Hema Malini, Beena Banerjee

Synopsis: Sameer Niyogi (Vinod Khanna) encounters a mysterious woman, leading to a captivating tale set in Rajasthan.

This movie, produced by Lata Mangeshkar, is not a direct adaptation but rather an inspiration from Tagore’s original story wherein the protagonist, a fresh-faced tax collector, finds himself stationed in a quaint village. Opting to dwell in an ancient, decrepit palace, rumoured to be haunted, he dismisses the warnings of the townsfolk. They caution him that past occupants have either lost their sanity or met untimely demises, claiming the structure itself is voracious. Yet, he soon discovers a beguiling woman, shrouded in mystery, wandering the palace’s corridors under the cloak of darkness.

Music: The music was composed by Pt. Hridaynath Mangeshkar and the lyrics were penned by Gulzar. Each composition was unique and tugged at our heartstrings.

Trivia: This cinematic tale was brought to life from its literary origins in Bengali under the masterful direction of Tapan Sinha, the actors Soumitra Chatterjee and Arundhuti Devi graced the silver screen, weaving the characters into the fabric of our imaginations.

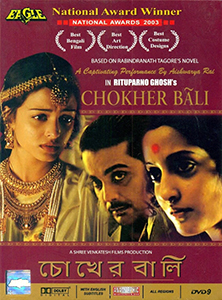

Sand in the Eye(2003)

Adapted Story: Chokher Bali (Eyesore)

Director: Rituparno Ghosh

Cast: Aishwarya Rai, Prosenjit Chatterjee, Raima Sen, Lily Chakravarty, Tota Roy Chowdhury

Synopsis: The tangled web of human relationships! Like a delicate spider’s silk, it ensnares us all, only to leave us dangling in a mess of our own making. Meet Binodini, a young widow, thrust into a world of moral ambiguity, where the lines between right and wrong are as blurred as the tears on her lovely face.

She finds herself in the midst of a most unsavoury triangle, with Mahendra, the self-absorbed cad, and his wife, Ashalata, who is naive and inexperienced. Mahendra, it seems, has a penchant for sampling the wares, only to discard them like a worn out [air of gloves. Binodini, however, is no fool, and she sees through his façade, recognizing the emptiness that lies beneath.

As the drama unfolds, we find ourselves entangled in a dance of deceit, where allegiances are forged and broken with all the finesse of a seasoned juggler. Behari, the stalwart friend, stands as a beacon of hope, a shining example of integrity in a sea of moral turpitude. But even he is not immune to the whims of fate, as Binodini’s mercurial heart leads him on a merry chase.

In the end, it is a tale of shattered dreams, of relationships reduced to tatters, like the fragile petals of a once beautiful flower. And yet, amidst the wreckage, we find a glimmer of hope, a testament to the human spirit’s capacity to endure, to persevere, and to love, despite the ravages of time and the cruel whims of fate. Ah, the human heart, that most confounding of puzzles, forever a mystery, forever a delight!

Music: The haunting strains of Debojyoti Mishra’s background score swirl around one, a melancholy mist that shrouds the narrative.

Trivia: This film is a dubbed version of the Bengali movie ‘Chokher Bali’.

Bioscopewala (2018)

Adapted Story: Kabuliwala

Director: Deb Medhekar

Cast: Danny Denzongpa, Geetanjali Thapa, Adil Hussain, Tisca Chopra

Synopsis: This cinematic offering is a departure from its literary progenitor. “Bioscopewala” chronicles the life of Rehmat Khan, a Kabulian cinemagician who regaled tykes with his flickering bioscope. Among his youthful admirers was Minnie, a lass of equal years to his own little cherub. But alas! Rehmat vanished as swiftly as a dodo, leaving Minnie to ponder his abrupt departure.

Fast forward, and Minnie, now a documentarist residing in the land of croissants and mime artists, stumbles upon a startling revelation: her father perished in an aerial catastrophe while attempting a pilgrimage to Afghanistan. Driven by an unquenchable thirst for knowledge, Minnie reunites with Bioscopewala, the narrator of her childhood adventures, to unravel the enigmatic circumstances surrounding her father’s fateful journey.

Prepare yourself for a tale that interweaves the whimsical with the poignant, where the complexities of human existence unfold amidst the flickering shadows of a Bioscope. May this cinematic concoction tickle your intellect and leave you pondering the true nature of life’s grand and enigmatic spectacle.

Music: There is only one song in the film, titled “Bioscopewala.” It was sung by K Mohan, and composed by Sandesh Shandilya, with lyrics written by Gulzar.

Influences of Tagore in Bollywood

In addition to the films I’ve already mentioned, here are a few Bollywood movies I can recall that are heavily influenced by Tagore’s works.

Do Bigha Zamin (1953)

Adapted Poem: Dui Bigha Jomi (Two Bighas of Land)

Cast: Balraj Sahni, Nirupa Roy, Ratan Kumar, Nana Palsikar, Meena Kumari, Mehmood

Director: Bimal Roy

Synopsis: The tale centres on Shambhu Maheto, a humble farmer living in a drought-stricken village with his family. When the rains finally arrive, Shambhu’s joy is short-lived as the scheming landlord, Harnam Singh, eyes Shambhu’s precious two bighas of land for a profitable mill project. Despite Shambhu’s desperate attempts, including selling all household items and moving to Calcutta to earn money, he fails to repay the inflated debt. His journey in Calcutta is fraught with hardship, culminating in his wife’s injury and his son’s foray into petty crime. Ultimately, Shambhu returns home to find his land auctioned off and a factory replacing his farm, leaving his family to walk away from their former life with nothing but memories.

Music: Salil Chowdhury composed the music for the film, with lyrics penned by Shailendra. In an interview with All India Radio, Chowdhury explained that the melody for “Apni Kahani Chod Ja – Dharti kahe pukaar ke” was inspired by a Red Army march song. Lata Mangeshkar, Manna Dey and Mohd. Rafi lent their voices.

Durban (2020)

Adapted Story: Khokababur Protyabartan (The Return of the Child)

Director: Bipin Nadkarni

Cast: Sharib Hashmi, Sharad Kelkar, Rasika Dugal, Flora Saini

Synopsis:, This film tells the story of a wealthy man’s son and his caretaker. Despite their social differences, they share a deep bond. However, an unfortunate incident drives them apart, leading the caretaker on a journey of redemption.

Music: The film’s soundtrack is composed by Amartya Bobo Rahut and Raajeev V. Bhalla, with lyrics written by Manoj Yadav, Siddhant Kaushal, and Akshay K. Saxena. Arijit Singh lent his voice.

Laapataa Ladies (2024)

Adapted Story: Noukadubi (The boat wreck)

Cast: Nitanshi Goel, Pratibha Ranta, Sparsh Shrivastav, Chhaya Kadam

Director: Kiran Rao

Synopsis: In 2001, in fictional Nirmal Pradesh, farmer Deepak travels with his new bride, Phool Kumari. On a crowded train, amidst other veiled brides, Deepak dozes off and accidentally disembarks with the wrong bride, Jaya, leaving Phool with another groom, Pradeep. The mix-up mirrors Rabindranath Tagore’s “Noukadubi.”

Deepak’s family realizes the mistake but Jaya, using the name Pushpa, lies about her identity. Phool, stranded at another station, is helped by Manju Mai. Deepak, searching for Phool, files a report. Jaya is arrested but reveals her troubled past and desire for independence. Eventually, Phool reunites with Deepak, and Jaya pursues her education.

Besides the wife-exchange element, there is little in common between this movie and the works of Tagore. The theme of women’s empowerment takes centre stage. If Manju Mai cautions Phool in respect of the ills of patriarchy, Jaya breaks the matrimonial bond with a self-centred, greedy and domineering husband. Instead, she decides to pursue an independent course in life.

Music: The film’s music was composed by Ram Sampath, featuring lyrics by Divyanidhi Sharma, Prashant Pandey, and Swanand Kirkire.

Conclusion

As we stand at the threshold of the great unknown, it is the poet-philosophers who have always dared to illuminate the darkness that lies beyond. Like the Dutch sage Spinoza, who glimpsed the infinite in the finite, and Wordsworth, who in his sublime poem “A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal” wrote,

“No motion has she now, no force;

She neither hears nor sees;

Rolled round in earth’s diurnal course,

With rocks, and stones, and trees.”

Rabindranath Tagore, the great Bard of India, has similarly beheld death not as an end, but as a new beginning, a gateway to the eternal.

To Tagore, death is not the extinguishing of the flame, but the merging of the individual spirit with the universe, a reunification that sets the stage for a new drama of thought to unfold. As he so eloquently put it, death is merely the “reunion of one’s spirit to the universe and thereby to eternity,” a notion that transcends the petty boundaries of mortality. It is here, in this realm of eternity, that the legacy of thought germinates, and the development of a society can continue, unfettered by the constraints of time and space.

And so, as we ponder the mystery of death, we would do well to recall Tagore’s wise words: “The song that I came to sing remains unsung to this day. I have spent my days in stringing and in unstringing my instrument.” For, in the end, it is not the song that we sang, but the song that we came to sing, that truly matters. And it is in this eternal realm, where thought and spirit converge, that our true legacy resides, waiting to be discovered, and sung anew.

So dear readers, as we fondly remember him on the day he embarked on his celestial journey, I wish to thank you for going through my musings on how Bollywood has honoured his legacy through its cinematic endeavours. I am certain that the list I have presented to you here is merely indicative and not exhaustive.

Which are the other movies you would like to add to this list of mine? Please leave a comment below, mentioning the name of the movie and its year of release. I shall be obliged.

Related Post:

Where the Mind is without Fear

Tribute to a Cinematic and Literary Genius: Guest Post by Suryamouli Datta

Read Full Post »