Posts Tagged ‘Movies’

A Tribute to Raj Khosla by Dustedoff

Posted in The Magic of Movies!, tagged Bollywood, Hindi, Kaala Paani, Movies, Raj Khosla, Suspense on June 9, 2025| Leave a Comment »

Remembering Suchitra Sen, the ‘Mahanayika’: Guest Post by Shivdas Nair

Posted in The Magic of Movies!, tagged Bengali, Bollywood, Movies, Suchitra Sen, Tollywood, Tribute on April 7, 2025| Leave a Comment »

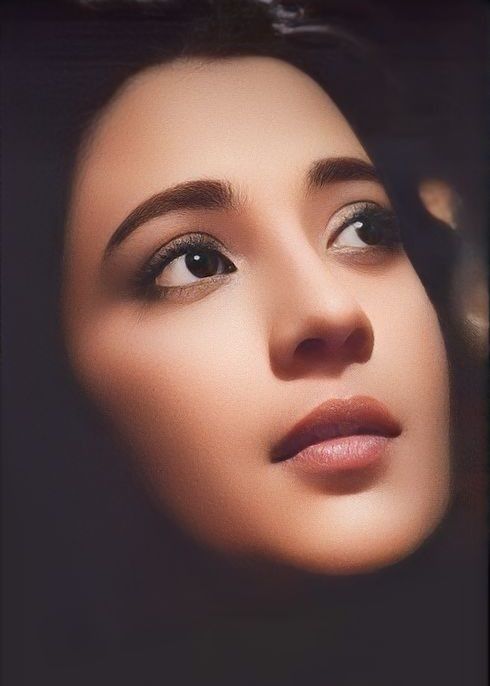

For more than six decades, Suchitra Sen, originally named Roma Dasgupta, stood as the undisputed queen of Bengali cinema, embodying the essence of Bengali femininity, beauty, and elegance. Even after her unexpected withdrawal from the public eye in 1978, her allure and mystique remained intact; in fact, her choice to retreat into seclusion only deepened the intrigue surrounding her.

It is believed that one of director Sukumar Dasgupta’s assistants was responsible for bestowing upon Roma Dasgupta the iconic screen name, Suchitra Sen. Sukumar Dasgupta was the director of her debut film, Saat Number Kayedi.

Her passing on January 17, 2014, signified the conclusion of a remarkable era in Bengali cinema.

The Suchitra Sen phenomenon was unprecedented in the history of Bengali cinema. Not only was she the leading female actor of her time, but she also emerged as one of the most significant stars to grace the Bengali film industry, with her widespread popularity rivaling only that of Uttam Kumar, with whom she shared the screen in 30 of her 60 films. She was the first and only actress to earn the title ‘Mahanayika,’ a distinction that was only similarly awarded to Uttam Kumar in Bengali cinema.

During the height of her fame in the 1950s and 1960s, it is estimated that she commanded a fee of around ₹ 1 lakh per film. Her immense star power made her a central figure in the film industry, often featured prominently on movie posters, and her name was typically highlighted even more than that of the male lead, with the exception of Uttam Kumar, where they shared equal prominence.

The partnership of Suchitra Sen and Uttam Kumar on screen marked a pivotal era in Bengali cinema. Their collaboration spanned 30 films, starting with Sharey Chuattar in 1953, and significantly altered the landscape of Bengali film history. For over two decades, from 1953 to 1975, Suchitra and Uttam reigned supreme in the industry, delivering memorable hits such as Agnipariksha, Shap Mochan, Sagarika, Harano Sur, Indrani, Saptapadi, and Bipasha.

They became icons that resonated with the youth, embodying their dreams and aspirations. Their undeniable on-screen chemistry was so powerful that they transcended their individual stardom, merging into a single entity: Suchitra-Uttam or Uttam-Suchitra. Uttam Kumar himself acknowledged this bond, stating, ‘Had Suchitra Sen not been by my side, I would never have been Uttam Kumar.’

Suchitra is hailed as the first style icon of Bengali cinema, with her unique mannerisms inspiring generations of young Bengali women. The characters she portrayed were often progressive, reflecting the aspirations of women ahead of their time. In many of her films, she took on the roles of ‘professional women,’ whether as an artist in Jiban Trishna, a doctor in Harano Sur, or a politician in Aandhi.

Madhuja Mukherjee, an associate professor of Film Studies at Jadavpur University, noted, ‘Her star persona was shaped by her roles. She exuded a remarkable star quality, both in her appearance and her performances. Compared to the societal norms of her time, she was almost placed on a pedestal, embodying the aspirations of women.’ Remarkably, according to Mukherjee, Suchitra maintained her status as a leading star throughout the 1960s, even as she entered her thirties.

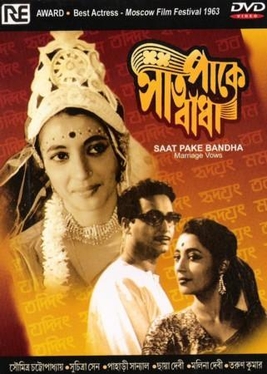

Suchitra’s stunning beauty and immense fame frequently eclipsed her acting talent. Nevertheless, she made history as the first Indian actress to win the best actress award at an international film festival, receiving the honor for her role in Saat Paake Bandha (1963) at the Moscow International Film Festival. Her star power was well-recognized in the Hindi film industry, where she appeared in several major films, including Devdas, Bambai Ka Babu, Mamta, and Aandhi.

Born on April 6, 1931, in Pabna, now part of Bangladesh, Roma was one of eight siblings. Her father, Karunamoy Dasgupta, served as a school headmaster, and she was raised in a culturally rich environment. The Partition led her family to West Bengal, and Roma, already a captivating beauty, soon married Dibanath Sen, the son of a prosperous industrialist. Before venturing into acting, Roma aspired to pursue a music career and reportedly recorded several songs in her own voice.

Despite the admiration she garnered and the unwavering attention from her devoted fans, Suchitra Sen remained a mystery. Known as ‘Mrs Sen’ in the film industry, she was often viewed as distant and hard to approach. By the time she entered the film world, she was already a married woman and a young mother, and her striking looks, reserved demeanor, and privileged background often intimidated those around her. However, she was also recognized for her warmth and friendliness.

Veteran actress Moushumi Chatterjee remarked, ‘Suchitra Sen embodied elegance. She had a remarkable ability to distinguish her personal life from her public persona.’

Industry insiders believe that Suchitra’s keen awareness of her own celebrity status contributed to the myth surrounding her. This understanding may explain her enduring reign as the queen of Bengali cinema and the continued fascination with her, even 36 years after she chose to live in complete seclusion. Her abrupt withdrawal from the public eye only heightened interest in her, sparking numerous discussions, debates, and theories about the reasons behind her choice to retreat.

Rarely spotted in public, she became the most renowned recluse in West Bengal, drawing comparisons to Hollywood’s Greta Garbo. Her commitment to privacy and the lengths she reportedly went to maintain it often seemed almost obsessive.

In 2005, she allegedly declined the Dada Saheb Phalke Award because accepting it in person would compromise her privacy. Even in death, she preserved her enigmatic aura: her final journey was conducted in a black-tinted hearse, obscuring her body from public view.

Suchitra Sen had never collaborated with any of the three giants of Bengali parallel cinema: Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, or Mrinal Sen. According to reports, she turned down an opportunity to work with Satyajit Ray because he requested that she refrain from taking on other projects while filming. Suchitra expressed her willingness to honor her commitment to him but was unwilling to promise exclusivity. As a result, the collaboration fell through, and Satyajit Ray ultimately abandoned the project.

While discussing her views on Hindi actors, she touched upon her decision to decline a collaboration with Raj Kapoor. Suchitra explained that the reason for her refusal stemmed from an encounter where the legendary actor and director positioned himself near her feet and presented her with a bouquet of roses. She expressed her preference for men who engage in sharp, intelligent dialogue, which made her uncomfortable with Raj Kapoor’s gesture.

Suchitra Sen and Dharmendra starred together in the film Mamta, directed by Asit Sen. According to a report, Suchitra recounted an incident where Dharmendra unexpectedly kissed her on the back during a scene. She revealed that this moment was not scripted, but the director, Asit Sen, found it compelling enough to include in the final cut of the film. Describing it as an ’embarrassing moment,’ Suchitra made it clear that she was not fond of Dharmendra’s spontaneous kiss.

The world had undergone significant changes in those 36 years of her seclusion, yet the image of Suchitra Sen remains timeless. This enduring presence continues to resonate with the Bengali community, as demonstrated by the large crowds of all ages that filled the streets of Kolkata during her final farewell.

While many regarded Suchitra Sen’s passing as a profound loss for the film industry, the esteemed director Buddhadeb Dasgupta offered a poignant perspective: ‘She will forever be celebrated as the greatest heroine of Bengali cinema. No one can rival her mass appeal. However, the industry truly lost her when she chose to live in seclusion over 30 years ago.’

Suchitra Sen has been honored with four BFJA Awards, the Best Actress Award at the 3rd Moscow International Film Festival, a Filmfare Bangla Award, the Filmfare East Lifetime Achievement Award, the Banga Bibhushan, and the Padma Shri.

Today marks Suchitra Sen’s 94th birthday, a perfect occasion to celebrate her remarkable film legacy. You can catch some of her iconic performances on Prime Video, where titles like Agnipariksha, Sagarika, Indrani, Bipasha, and Devdas are available. On YouTube, check out Shap Mochan, Harano Sur, Saptapadi, Jiban Trishna, Aandhi, Bambai Ka Babu, Mamta, and Uttar Phalguni. On Hoichoi, don’t miss Saat Paake Bandha, Deep Jwele Jai, and Sharey Chuattar.

Notes

- A version of this article first appeared in The Reviewer Collective group on Facebook. The author’s consent to reproduce it here is gratefully acknowledged.

- I believe that after she retired from acting, she lived in Pondicherry for a few years as a reclusive inmate of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram.

- All the visuals are courtesy the World Wide Web.

Remembering Basu Chatterjee: Guest Post by Shivdas Nair

Posted in The Magic of Movies!, tagged Basu Chatterjee, Bollywood, cinema, Directors, Entertainment, Gulzar, Hindi Movies, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Movies on January 16, 2025| 2 Comments »

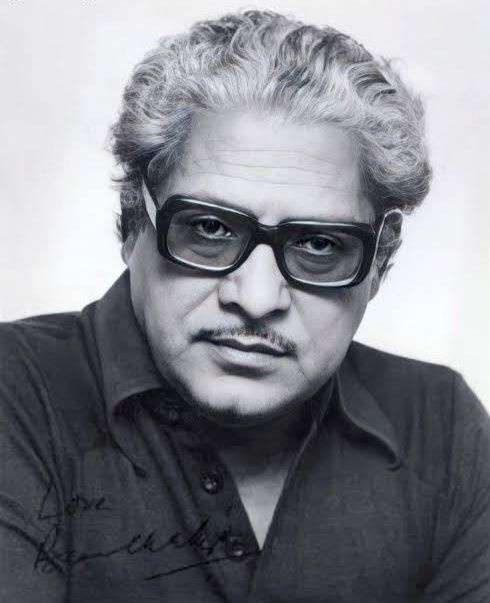

Basu Chatterjee was a champion of the middle class, who turned ordinary lives into captivating stories. His films showcased relatable characters dealing with real challenges, making their triumphs and losses deeply affecting us.

Basu da had a unique way of showing female characters. He was curious about women’s thoughts and dreams, exploring their views on romance and meaningful relationships, both romantic and platonic.

He began directing in 1969 with his film Sara Akash, starring FTII-trained actor Rakesh Pandey. The story, set in Agra, follows a newlywed couple dealing with the challenges of an arranged marriage in a joint family. This year marked the onset of the first wave of parallel cinema, showcasing films like Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome and Mani Kaul’s Uski Roti. However, the audience for these films, including Sara Akash, remained largely confined to film festivals.

Basu Chatterjee first gained attention with his 1974 film, Rajnigandha, which is based on Manu Bhandari’s Hindi short story Yahi Sach Hai. The film looks at a woman’s struggle between her current partner and an ex who returns, evoking past emotions. Rajnigandha established Chatterjee’s unique filmmaking style. It featured newcomers Amol Palekar and Vidya Sinha, with mostly unknown actors, except for Dinesh Thakur. Chatterjee made a cameo as an annoyed moviegoer. The film’s music, by Salil Chowdhury with lyrics by Yogesh, included memorable songs. Its success led to lasting collaborations among Basu, Yogesh, Chowdhury, and cinematographer K. K. Mahajan. Shyam Benegal’s Ankur also found success that year, demonstrating that art and commerce could indeed thrive together.

He was a pioneering filmmaker who highlighted the Parsi community in Khatta Meetha, showing them authentically and avoiding clichés. Similarly, Baaton Baaton Mein focused on the Catholic community in Bandra, also avoiding stereotypes. Basu da’s films found romance in daily life in Bombay, whether on crowded trains, buses, or Delhi streets.

Basu Chatterjee, along with Gulzar and Hrishikesh Mukherjee, formed a strong trio that shaped middle-of-the-road cinema in the 1970s. Their films appealed to middle-class Indians longing for unique yet relatable stories, combining mainstream charm, memorable music, real emotions, and uplifting narratives based on everyday life.

Basu da was born in Ajmer on the 10th of January, 1927. Being close to his 98th birth anniversary, let me highlight a few of his timeless classics.

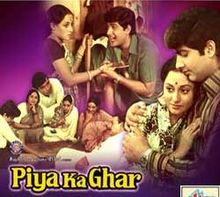

Piya Ka Ghar is a film featuring Jaya Bhaduri and Anil Dhawan, and is a remake of the Marathi film Mumbaicha Jawai. It tells the story of the difficulties faced by married couples in Mumbai, particularly due to limited living space. Malti, a girl from a village, marries Ram through a matchmaker but feels disappointed when she learns they must live with his extended family in a cramped apartment, which affects their privacy and intimacy. Available on Prime Video.

Rajnigandha, based on Mannu Bhandari’s short story Yahi Sach Hai, features Vidya Sinha as a woman torn between two suitors and takes her time to select a husband, a departure from typical glamorous roles. The film centers on the simple lives of three middle-class people without unnecessary melodrama. Vidya’s performance received praise from critics and audiences alike. The film marked the introduction of Amol Palekar and Vidya Sinha, and included memorable songs sung by Lata Mangeshkar and Mukesh, who won a National Award for their work. Available on Prime Video.

Chhoti Si Baat features Amol Palekar as a shy man who hires a life coach to learn how to propose to a girl. Palekar plays an introverted character, while Vidya portrays a woman who knows his feelings and waits for him to act. The film connects well with audiences due to its middle-class setting. It also includes beautiful music by Salil Chaudhury, showcasing Yesudas’ talent in the duet, Jaaneman Jaaneman Tere Do Nayan, filmed with Dharmendra and Hema Malini. Available on Prime Video.

Chitchor is a romantic comedy about mistaken identities involving Geeta and her family eager for her to meet an eligible bachelor, Sunil, who is coming to their village. However, when overseer Vinod mistakenly arrives instead, he wins the affection of Geeta, who wants to marry him. The arrival of Sunil complicates matters as he also develops feelings for her. The film includes lovely songs by Ravindra Jain, such as Jab Deep Jale Aana. Available on Prime Video.

Swami is based on Sarat Chandra’s novel of the same name and follows Saudamini, played by Shabana Azmi, who admires her uncle while facing approval issues from her mother regarding her friendship with Naren. After marrying Ghanshyam, a kind wheat merchant, she feels trapped but learns of her husband’s true kindness. The film concludes with her transformation into a devoted wife, showcasing Azmi’s impressive performance. Available on YouTube.

Khatta Meetha is inspired by the American classic Yours, Mine and Ours and tells the story of a middle-aged widower, played by Ashok Kumar, who marries a widow, portrayed by Pearl Padamsee. They both have children from previous marriages and face challenges in merging their families as the siblings conflict. Yet, through various trials, the family finds ways to unite and coexist peacefully, depicting a heartwarming conclusion. Available on YouTube.

Baton Baton Mein is set in a Christian context and highlights the courtship of Amol Palekar and Tina Munim, with the help of her uncle, played by David. Rosie, a widow, wants her daughter to marry, while Nancy meets Tony on their daily commute. Tony’s shyness creates tension, prompting Rosie to look for other matches, but her uncle’s intervention helps reconnect Tony and Nancy. The film had some lovely songs like Suniye Kahiye Kahiye Suniye, Na Bole Tum Na Maine Kuch Kaha and Uthe Sabke Kadam tuned by Rajesh Roshan. Available on Prime Video.

Apne Paraye, inspired by Sarat Chandra’s novel Nishkriti, revolves around Utpal Dutt, a lawyer with a fondness for his cousin Chander (Amol Palekar), who prefers music over a steady job. Chander’s wife, Sheela (Shabana Azmi), is the strict one in the household. Their stable lives are disturbed when Utpal’s younger brother arrives with his wife, creating a complex family dynamic filled with rivalries. Available on Prime Video.

Shaukeen is adapted from the American comedy Boys’ Night Out and follows the lighthearted misadventures of three elderly men, played by Ashok Kumar, Utpal Dutt, and A K Hangal, who fantasize about romance while trying to meet a young woman. They embark on a trip to Goa thanks to their driver, Ravi, leading to humorous yet respectful situations. Ashok Kumar and the ensemble cast deliver exceptional performances throughout. Available on Prime Video.

Chameli Ki Shaadi represents a groundbreaking film tackling caste discrimination with a strong feminist lead. Charandas, (Anil Kapoor), is engrossed in wrestling but loses focus when he meets Chameli (Amrita Singh). Their love faces familial opposition due to caste differences, and to find a solution, they consult an advocate Harish (Amjad Khan), who suggests they elope. Available on YouTube.

One notable aspect of Basu da’s films was their exceptional music. He collaborated with a variety of music directors, including Salil Chowdhury, R D Burman, Laxmikant Pyarelal, Bappi Lahiri, Jaidev, and more. However, his most fruitful partnership was with Rajesh Roshan, producing memorable soundtracks for films like Swami, Khatta Meetha, Baaton Baaton Mein, Priyatama, and Hamari Bahu Alka.

The Chaterjee-Roshan duo have given some memorable songs, like, Pal Bhar Mein Yeh Kya Ho Gaya (Swami), Aaye Na Baalam (Swami), Koi Roko Na Deewane Ko (Priyatama), Tere Bin Kaise Din’(Priyatama), Thoda Hai Thode Ke Zaroorat Hai (Khatta Meetha), Badal Toh Aaye (Dillagi), Na Bole Tum Na Maine Kuch Kaha (Baaton Baaton Mein), Suniye Kahiye (Baaton Baaton Mein), Charu Chand Iss Chanchal Chitwan (Man Pasand), Prem Ki Hai Kya Sun Paribhasha (Hamari Bahu Alka), and many more.

In the 1980s, the number of supporters for his style of filmmaking dwindled, prompting Basu Chatterjee to transition to television. His debut serial, Rajani, featuring Priya Tendulkar, was a pioneering effort in consumer activism in India. Following Rajani, he directed other notable television series such as Darpan and Kakkaaji.

Basu Chatterjee received the Filmfare Best Director award for Swami, which also earned a National award. He was honoured with six Filmfare Awards – Critics for Screenplay.

In the new millennium, remakes of Chitchor and Shaukeen emerged, but they failed to capture the charm of the originals. Today, the success of films like Bareilly Ki Barfi and Badhaai Ho serves as a testament to the legacy of Basu Chatterjee’s cinematic style.

About the author

Shivdas Nair has been a cinephile for years. However, he has just started putting his thoughts on paper. A media professional for over two and half decades, and with changing times, now a Principal Advisor – Growth with a vibrant and innovative IT Consulting & Advisory Services company, i-Gizmo Global Technologies. He has just started blogging at https://thoughtsoveracuttingchai.blogspot.com.

Notes

- A version of this article first appeared in The Reviewer Collective group on Facebook. The author’s consent to reproduce it here is gratefully acknowledged.

- All the visuals are courtesy the World Wide Web.

Related Post

Remembering The Timeless Voice of Ameen Sayani: Guest Post by Anupam Ganguli

Posted in The Magic of Movies!, tagged Ameen Sayani, Binaca Geet Mala, Bollywood, Cibaca Geet Mala, Entertainment, Hindi, Movies, Radio Ceylon, Songs on December 23, 2024| Leave a Comment »

A voice that once resonated in the hearts of millions, Ameen Sayani’s journey through the golden age of radio is quite like a poetic legacy.

RJ-ing may be deemed modern and cool, but decades ago, Sayani redefined the art of storytelling, transforming radio waves into a mesmerising canvas of music, humour and heartfelt connection.

Through Binaca Geet Mala, later Cibaca Geet Mala, he brought alive songs in the minds of his listeners, making every home a stage and every heart a participant.

Sayani’s style was a symphony of modesty and charm.

Unlike the exuberant style of today’s RJs, he spoke softly, weaving nuggets of trivia, artiste anecdotes and public sentiments into a magical fabric.

His humour was gentle yet infectious, his knowledge vast yet accessible.

Listeners adored him for this balance, often valuing his voice over the songs he introduced.

The anticipation surrounding Binaca Geet Mala was unequalled.

Each week, families would assemble around the radio, waiting with bated breath to hear which song had claimed the coveted number one spot.

Behind the scenes, Sayani and his team meticulously curated rankings, with decisions accepted unquestioningly, a nod to his credibility.

Songs retired after 25 runs were saluted with dignity and a bugle, a ritual that amplified the programme’s charm.

In an era when radios were scarce, Sayani’s voice unified neighbourhoods, families, and even nations.

Broadcasting via Radio Ceylon, Binaca Geet Mala held sway for an extraordinary 42 years, a record that remains unbeaten.

His catchphrase greeting Bhaiyon aur behnon became a cultural phenomenon, as did the thousands of letters he received monthly from devoted fans.

Artistes revered him.

For musicians, singers, and composers, landing on Sayani’s charts was akin to earning a badge of honour.

The industry hung on his words, their hearts racing at his every announcement.

Such was his influence that Binaca Geet Mala turned chart-topping songs into timeless classics.

Beyond his flagship show, Sayani helmed iconic programmes like S. Kumar’s Filmi Mukadma and the Bournvita Quiz Contest.

His staggering repertoire, over 54,000 radio programmes and 19,000 jingles, stands as a monumental feat in broadcasting history.

Fluent in multiple languages, he reached a diverse audience, his voice bridging cultural and linguistic divides with ease.

Born in Bombay on 21st December, 1931, Sayani’s journey began at Scindia School and St. Xavier’s College, but it was his golden voice that would etch his name into history.

Honoured with the Padma Shri in 2009, he also made cameo appearances in a few films like Bhoot Bangla and Teen Deviyaan.

On 21st February, 2024, at the age of 91, Ameen Sayani’s voice fell silent.

Yet, his echo lingers, a melodic reminder of an era when radio was king, and one man’s voice united a nation.

Note

- Collage visual courtesy the world wide web.

- This article had first appeared in The Reviewer Collective group on Facebook.

Related Posts

Bollywood’s Love Affair with Umbrellas: Guest Post by Anupam Ganguli

Posted in The Magic of Movies!, tagged Bollywood, Entertainment, Movies, Rains, Romance, Umbrellas on December 5, 2024| Leave a Comment »

For decades, Bollywood has showered us with unforgettable moments of romance under the rain, from shy glances under flickering streetlights to stolen moments beneath a sheltering umbrella. This humble prop, in Bollywood’s hands, transforms into much more than a simple shield from the rain. It becomes a cocoon, a private world that magically brings lovers closer, often igniting romance or intensifying feelings against the backdrop of monsoon showers.

Iconic and Unmatched – Shree 420 (1955)

Raj Kapoor and Nargis’ Pyar Hua Iqrar Hua remains Bollywood’s most legendary and unforgettable love scene under an umbrella. Here, the umbrella is a literal and a figurative shelter, a cocoon. Their rain-soaked declaration of love is still unmatched, symbolising romance that defies storms.

Rekindled Love – Kala Bazaar (1960)

Dev Anand and Waheeda Rehman’s enchanting stroll in Kala Bazaar unfolds the beautiful melody of Rimjhim Ke Tarane, an ode to love rekindled amidst the soothing Mumbai rains. This iconic scene captures the essence of timeless romance and heartfelt connection.

Enchanting Gem in Motion – Boond Jo Ban Gayi Moti (1967)

In the vibrant cinemascape of Bollywood, Jeetendra shines like a dazzling jewel. Especially in the enchanting song Ye Kaun Chitrakaar Hai, his innocent charm as the village educator weaves a spell. His trademark umbrella in hand, he renders a song which is an ode to the creator of this universe.

Fragile Beginnings – Rajnigandha (1974)

In Rajnigandha, a broken umbrella offered by Amol Palekar to a Vidya Sinha stranded in a heavy downpour embodies the characteristics of a budding romance on the horizon. The scene beautifully captures the uncertainty, the hesitation, and the warmth of an empathic gesture. Based on the short story “Yehi Sach Hai” by noted Hindi writer Mannu Bhandari, Vidya Sinha’s character finds itself drawn back to a former flame. She is caught between past and present. How she overcomes this challenge forms the rest of the story.

Mystery Under Umbrellas – Judaai (1980)

In Judaai, Rekha and Jeetendra huddle together beneath an umbrella, creating a cocoon of secrecy and intimacy. This iconic moment beautifully encapsulates Bollywood’s enduring fascination with fleeting, stolen moments of love, highlighting the magic found in cherished connections.

Mera Kuch Samaan – Ijaazat (1987)

While umbrellas often signal romance, in Ijazat’s Mera Kuch Samaan, they represent nostalgia and lost love. As the song transports audiences through Anuradha Patel’s lyrical memories, the umbrella becomes a portal into the past, a shelter that once held warmth but now feels like an echo of something lost. Gulzar’s lyrics, in particular, Ek Akeli Chhatri Mein Aadhe Aadhe Bheeg Rahe They, Aadhe Sookhe, Aadhe Geele…captures a deep sense of nostalgia.

Iconic Sridevi Moments – ChaalBaaz (1989)

Sridevi’s iconic transparent umbrella in ChaalBaaz transcends mere props, becoming a vibrant symbol of her infectious playfulness and captivating charm. The song Na Jaane Kahaan Se Aayi Hai echoes the same magic, capturing a sense of wonder and spontaneity, much like Sridevi’s presence under that iconic umbrella.

Romantic Night – Afsana Pyar Ka (1991)

Aamir Khan serenading Neelam beneath an umbrella in Afsana Pyar Ka is a timeless tribute to Bollywood’s love for rain-laden romance. The song Tip Tip Tip Baarish Shuru Ho Gayi reiterates this sentiment, with its playful yet tender tone, as the rain becomes a backdrop for the blossoming connection, transforming the moment into a celebration of love’s simple joys.

Colourful Romance – Khiladi (1992)

Akshay Kumar and Ayesha Jhulka’s Khiladi brings to life playful moments under vibrant umbrellas, infusing their budding romance with a burst of colour, energy and innocence. Dekha Teri Masti Nigahon Mein captures this light-hearted spirit, with its playful rhythm reflecting the ease and charm of a love that blooms effortlessly, even in the rain.

Mountain Rains – 1942: A Love Story (1994)

The rain-soaked landscapes of Himachal provide the perfect backdrop for 1942: A Love Story, where Manisha Koirala’s red umbrella against Anil Kapoor’s embrace brings the song Rimjhim Rimjhim to life in a delicate, timeless romance.

Joyous Drizzles – Dil To Pagal Hai (1997)

Yash Chopra, known for cinematic romance, uses rain brilliantly in Dil To Pagal Hai. Shah Rukh Khan, under the spell of Madhuri Dixit’s smile, jokes that her smile causes a downpour before they dance joyfully in Chak Dhoom Dhoom. The rain here becomes an extension of their happiness and spark. Umbrellas make a sporadic appearance, though – first in the very beginning, and then later when Karishma gets escorted back by the hospital staff.

Rain in The Big Apple – Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003)

In Kal Ho Naa Ho, Preity Zinta and Saif Ali Khan share an umbrella under New York’s rain, portraying friendship and affection amidst city lights. The rain-filled scene captures a mix of sweet nostalgia and urban romance.

Rain-soaked Realisations – Hum Tum (2004)

In Hum Tum, Rani Mukerji’s Rhea and Saif Ali Khan’s Karan find their love during a cold, rainy night. Rhea cares for Karan, who is drunk, and in that moment of vulnerability, their mutual feelings emerge. Lamhon Ki Guzarish Hai Yeh highlights moments where the rain acts as a backdrop to acknowledge love. Needless to say, umbrellas do put in a brief appearance.

A journey of Innocence and Hope – The Blue Umbrella (2005)

In The Blue Umbrella, the umbrella becomes a symbol of innocence and self-discovery. As the story unfolds, the simple act of holding the umbrella in the rain transforms into a journey of emotional growth for Pooja. The song Chatri Ka Udan Khatola carries this spirit, as the umbrella takes flight, not just through the skies but through the heart, weaving together themes of hope, dreams, and the quiet beauty of life unfolding under the rain.

Old-World Aesthetics – Saawariya (2007)

In Saawariya, Sonam Kapoor and Ranbir Kapoor’s romantic journey unfolds under Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s signature aesthetic. The umbrella in this film adds to the story’s vintage, dreamlike quality, even as their love story remains an unfulfilled yearning.

Saccharine Romance – Cheeni Kum (2007)

In London’s drizzling charm, every shared moment beneath the umbrella, helps blossom Amitabh and Tabu’s bond, proving that even the simplest things, like a rain-soaked city and a shared shelter, can weave stories of connection and understated romance.

A Captivating Tribute to Timeless Love – Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi (2008)

With Phir Milenge Chalte Chalte in Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi, Bollywood’s magic unfolds in a mesmerising homage to love across eras. Shah Rukh Khan and a bevy of heroines capture the essence of timeless romance, dancing through Bollywood’s golden moments. The very first sequence is a loving tribute to the umbrella of Shri 420 fame, as mentioned above.

Fantasy in Polka Dots – 3 Idiots (2009)

In 3 Idiots, Aamir Khan and Kareena Kapoor light up the screen in a playful, dreamy sequence, dancing under polka-dotted umbrellas to the Zooby Dooby tune. This Bollywood-inspired rainy fantasy is a joyful tribute to the filmy romance we all adore.

Glamour and Chhatris – Race 2 (2013)

Deepika Padukone’s character in Race 2 shows that even the traditional umbrella can shine in high fashion. With her chic style, she seamlessly integrates this classic accessory, adding a sophisticated touch to Bollywood’s enchanting love affair with the rain.

Fashion Meets Rain – Kick (2014)

Jacqueline Fernandez in Kick brings a playful touch with her bright red umbrella, which adds flair to her character’s quirky look. It’s a lively reminder that umbrellas can also be fun, fashionable, and part of Bollywood’s colourful world.

Why Umbrellas Work: The Psychology of Umbrella Romance

Umbrellas naturally bring people closer together, creating a physical boundary that heightens the feeling of intimacy. They offer a shield from the outside world, creating a bubble of privacy even in the most public of places. The proximity, the shared warmth, and the playful tug-of-war as both try to fit under a single umbrella, these are elements that cinema uses to create moments of magic.

And in Bollywood’s signature use, umbrellas almost always appear when love is on the brink of blossoming or when emotions run high, turning mundane rainy-day encounters into moments of cinematic romance. They’re devices that trigger vulnerability, the need to protect, and the desire to draw close, lending themselves perfectly to Bollywood’s penchant for grand romantic expression.

A Lasting Symbol of Love and Shelter

From the monochromatic elegance of then to the vibrant visuals of now, umbrellas continue to hold a special place in Bollywood’s love stories. These cinematic moments remind us that sometimes, it’s the simplest things, a shared umbrella, a gentle rain, a crowded street, a song, that bring us closer, that make the world fall away so that all that remains is the quiet, breathtaking beauty of two souls meeting under a storm.

So the next time you find yourself in the rain, umbrella in hand, you might just be one scene away from your own Bollywood moment.

Related Posts:

Bingeing on subtitles: Guest Post by Suresh Subrahmanyan

Posted in The Magic of Movies!, tagged Binge-watching, Bollywood, Hollywood, Movies, Subtitles on December 2, 2024| Leave a Comment »

Exploring the Depths of Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot”: Guest Post by Suryamouli Datta

Posted in A Vibrant Life!, tagged Fyodor Dostoevsky, Literature, Movies, Russia, The Idiot on November 11, 2024| Leave a Comment »

Introduction

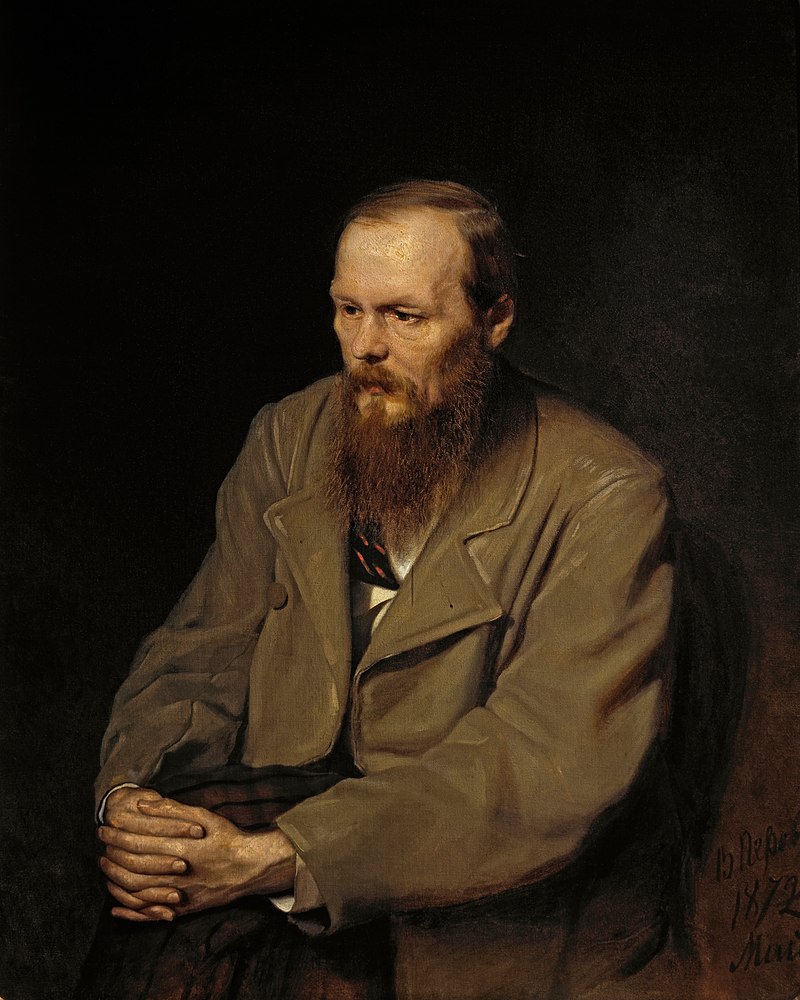

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot is a profound journey into the clash between innocence and the disillusionment of a morally complex society. First published in 1869, this novel remains a monument of philosophical inquiry and character depth. Dostoevsky, a visionary in Russian literature, was no stranger to human suffering and societal injustices. His own trials, including facing near-execution, find a voice in The Idiot. Through Prince Myshkin, Dostoevsky ventures into the possibility of purity in a world overcome by cynicism, greed, and moral ambiguity. Can innocence survive in a landscape marred by corruption? Dostoevsky invites us to ponder this question.

Dramatis Personae

- Prince Lev Nikolayevich Myshkin

Known as the “idiot” for his naive, unguarded nature, Myshkin stands as the embodiment of childlike idealism. He is described as a “positively beautiful man,” possessing a purity that starkly contrasts with the self-interest and moral ambiguity of those around him. Myshkin’s nature makes him vulnerable to manipulation, but his unwavering compassion and ability to forgive create an indelible impact on others. His words, “I’m sure you think me incredibly stupid, but I assure you that I understand many things” (Part 1, Chapter 7), resonate as an assertion of his deeper understanding beyond superficial judgments.

- Nastasya Filippovna

A tragic figure, Nastasya Filippovna is tormented by feelings of worthlessness and self-hatred. Her beauty captivates Myshkin and Rogozhin alike, but her traumatic past and self-destructive tendencies create a complex inner conflict. Her declaration, “I’m a nobody, a sick soul, I don’t deserve you” (Part 3, Chapter 3), reveals her deep-seated vulnerability and her struggle with self-acceptance, which drives much of the novel’s drama.

- Parfyon Rogozhin

Rogozhin, passionate and impulsive, serves as a dark counterpoint to Myshkin’s purity. His obsessive love for Nastasya Filippovna leads him down a destructive path, symbolizing love’s potential for ruin when tainted by possessiveness and jealousy. His volatile nature and capacity for violence create a tragic tension that culminates in inevitable disaster. Rogozhin’s intensity and Myshkin’s gentleness interact in a way that illustrates the broader dichotomy between purity and corruption.

- Aglaya Ivanovna

Representing idealism and the potential for happiness, Aglaya is drawn to Myshkin’s goodness but is constrained by societal expectations. Her struggle between her admiration for Myshkin and the weight of social pressure is poignantly expressed in her lament, “Why do they always make me do what I don’t want to do?” (Part 3, Chapter 8). Her character embodies the tension between personal desires and societal demands, further illustrating the novel’s exploration of unattainable ideals.

- Gavril Ardalionovich Ivolgin (Ganya)

An ambitious young man, Ganya seeks social mobility through a marriage to Nastasya Filippovna, driven by his desire for wealth and status. His conflicting feelings for Nastasya and his disdain for Myshkin’s ideals illustrate the personal costs of ambition and moral compromise.

- Ferdyshchenko

A minor character but essential for comic relief, Ferdyshchenko is outspoken and often disrupts social gatherings with his crude humour. He reflects the novel’s theme of hypocrisy by exposing the pretensions of those around him through his blunt honesty.

Plot Summary and Themes

The Idiot traces Myshkin’s return to Russia from a Swiss sanatorium, where his arrival in St. Petersburg sets off a series of events that unveil the moral and spiritual decay of the people around him. His genuine kindness and childlike honesty clash with society’s cynicism, resulting in misunderstandings and conflicts, especially around Nastasya Filippovna and Aglaya Ivanovna. Themes like innocence versus corruption, love’s complexities, and the ongoing struggle between good and evil make The Idiot a timeless masterpiece that critiques societal norms while examining the possibility of redemption. Dostoevsky’s philosophical views on justice and compassion, illustrated by Myshkin’s reflection on capital punishment, reveal his belief in a humane approach to morality—one that transcends the ordinary.

A pivotal moment in the book occurs during Nastasya’s dramatic party, where she throws 100,000 roubles into the fire, daring her suitors to retrieve it. This act symbolises her contempt for wealth and societal values, as she exclaims, “There’s no end to my vileness!” (Part 1, Chapter 15).

Myshkin on Capital Punishment

In The Idiot, Prince Myshkin’s commentary on capital punishment reflects Dostoevsky’s deep moral convictions and individual experiences. Myshkin recounts witnessing a guillotine execution in France, emphasising the psychological torment of the condemned rather than the physical pain. He argues that the preparations for execution—leading a man to the scaffold—are more horrific than the act itself, as they strip away humanity and instil profound fear. Myshkin’s belief that “thou shalt not kill” underscores his view that punishing evil with evil is fundamentally wrong, echoing Dostoevsky’s own traumatic near execution.

Historical and Biographical Context

Dostoevsky wrote The Idiot during a turbulent period in his life. After suffering through the death of his first daughter and facing financial difficulties, he sought to create a narrative that explored the possibility of a genuinely good and beautiful person. The novel was written in the late 1860s, a time of social and political upheaval in Russia, which is reflected in the characters’ struggles and societal critique.

Dostoevsky’s views on capital punishment were profoundly shaped by his firsthand experiences, particularly a mock execution he faced in 1849. Sentenced to death for his involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle, he was blindfolded and prepared for execution, only to be spared at the last moment. This psychological torture left a lasting impact, leading him to explore themes of suffering, compassion, and the moral implications of state-sanctioned death in his works, especially through the character of Prince Myshkin in The Idiot, who articulates the deep anguish of awaiting execution and the inherent cruelty of capital punishment.

Narrative Techniques and Character Relationships

Dostoevsky employs a variety of narrative techniques to bring depth to his characters and their relationships. The novel’s contrapuntal structure allows multiple voices and perspectives to coexist, creating a rich tapestry of conflicting ideologies and emotions. This approach provides insight into the characters’ inner lives and reflects the chaotic and multifaceted nature of human existence.

Prince Myshkin’s relationships with other characters are central to the novel’s exploration of moral integrity versus and corruption. His interactions with Nastasya Filippovna are particularly poignant, as he is drawn to her suffering and seeks to save her despite her self-destructive tendencies. Myshkin’s compassion for Nastasya is evident when he says, “I will follow you wherever you go, even to your grave” (Part 2, Chapter 7). This relationship highlights the tension between Myshkin’s idealism and the harsh realities of the world.

Similarly, Myshkin’s bond with Rogozhin is marked by a blend of friendship and rivalry, underpinned by their mutual obsession with Nastasya. Rogozhin’s passionate nature contrasts sharply with Myshkin’s gentleness, creating a dynamic that leads to tragedy. Rogozhin’s declaration, “You and I cannot live together; the one will destroy the other” (Part 4, Chapter 10), foreshadows the novel’s dramatic conclusion.

Myshkin’s relationship with Aglaya Ivanovna introduces another layer of complexity, as she represents a potential for happiness and normalcy. However, societal pressures and misunderstandings prevent their union, underscoring the novel’s theme of unattainable idealism. Aglaya’s struggle to reconcile her feelings for Myshkin with her family’s expectations is poignantly expressed when she asks, “Why do they always make me do what I don’t want to do?” (Part 3, Chapter 8).

Adaptations and Cultural Impact

Mani Kaul’s Ahamaq (1992) serves as a reinterpretation of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, adapting its themes to an Indian context. Both works explore the concept of “idiocy” through their protagonists—Prince Myshkin in The Idiot and his counterpart in Ahamaq, who struggles with epilepsy, often misinterpreted as madness.

While Dostoevsky’s narrative culminates in tragedy, reflecting societal cynicism, Kaul’s adaptation emphasises cultural nuances and the complexities of faith and desire within a contemporary Indian setting, offering a unique lens on the original themes of purity and delusion. In the television adaptation, Shah Rukh Khan portrayed the role of Rogozhin, Mita Vashisth the role of Nastasya, and M.K. Raina portrayed the role of Myshkin. Personally, I wish Shah Rukh had instead portrayed the role of Myshkin as he was doing enough negative roles on screen then.

Samaresh Basu’s novel Aparichita draws considerable influence from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. Both works explore themes of innocence, morality, and the complexities of human relationships. In Aparichita, the protagonist’s struggles mirror those of Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin, highlighting the tension between idealism and societal corruption. The narrative delves into the psychological landscapes of its characters, reflecting Dostoevsky’s polyphonic style, where multiple voices and perspectives coexist, enriching the emotional depth of the story. The film (1969) portrays Uttam Kumar as Rogozhin, Soumitra Chatterjee as Myshkin, and Aparna Sen as Nastasya. Soumitra Chatterjee’s performance in the movie was power-packed.

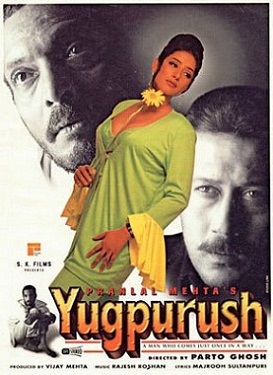

Additionally, the Bollywood film Yugpurush (1998) is based on Samaresh Basu’s novel Aparichita. The film starred Nana Patekar as Myshkin, Jackie Shroff as Rogozhin, and Manisha Koirala as Nastasya. The movie featured songs with music heavily influenced by Rabindra sangeet, composed by Rajesh Roshan. Yugpurush provides a fascinating lens on the themes of The Idiot, set within the Indian cultural milieu, and showcases the adaptability of Dostoevsky’s timeless themes.

Internationally also, The Idiot has inspired quite a few movies from such diverse countries as Russia, Germany, Japan, Estonia, and France.

The earliest example is that of Wandering Souls (German: Irrende Seelen), a 1921 German silent drama film directed by Carl Froelich and starring Asta Nielsen, Alfred Abel, and Walter Janssen.

Yet another example is that of L’idiot (1946), a French drama film which was directed by Georges Lampin and starred Edwige Feuillère, Lucien Coëdel and Jean Debucourt.

Conclusion

The Idiot remains a profound exploration of the human condition, examining the fragile balance between integrity and corruption. Dostoevsky’s masterful characterisations and narrative depth invite readers to ponder the true nature of goodness and the possibility of redemption. As we reflect on Myshkin’s journey, we are reminded of the enduring relevance of Dostoevsky’s vision of a world where compassion and integrity can shine, even in the darkest of times.

The Idiot remains as relevant as it was in Dostoevsky’s time. Humanity faces many challenges today. Wars. Poverty. Income disparities. Climate change. Challenges posed by rapid advances in technology. If we were to dig deeper, we are apt to discover that what we face is a crisis of leadership in all realms of human endeavour. The themes of authenticity, integrity, and morality have all been relegated to the background. Few big corporates rule the world. Social media puts blinkers on our eyes, masks the reality, and shapes our opinions. Forget carbon monoxide. Hate, cynicism, and hypocrisy also pollute the air we breathe in.

Myshkin’s journey resonates with contemporary readers facing a world where virtues are often overshadowed by self-interest and superficiality, reminding us of the power of goodness even in the darkest of circumstances. Dostoevsky’s portrayal of Myshkin’s kindness and compassion challenges readers to consider the value of empathy, sincerity, and integrity in our interactions with others.

References

- Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. Vintage Classics, 2003.

- CliffsNotes on The Idiot

- [Schlemiel Theory] (https://schlemielintheory.com/2014/11/26/what-happens-when-an-idiot-reflects-on-a-beheading-on-dostoevskys-reading-of-the

Related Post

BOLLY TEA – The Chai Culture in Bollywood Films: Guest Post by Anupam Ganguli

Posted in The Magic of Movies!, tagged Bollywood, Chai, Hindi, Indian, Movies, Tea on November 1, 2024| 2 Comments »

Ah, chai! That comforting, fragrant, and beloved Indian beverage that transcends being just a drink. In Indian cinema, chai holds a special place, often serving as a backdrop for pivotal moments, whether it is humour, romance, or heartfelt connections. Let us take a fun look at how tea has made its way into some of Bollywood’s most iconic moments and why it remains a cultural symbol in films.

The Chaiwala: More than just a vendor

The chaiwala is a character almost as quintessential to Bollywood as the heroes and heroines. Often found on the streets, busy markets, and humble villages, the chaiwalas offer more than just a cup of tea; they provide a setting for conversations, friendships, and life-changing decisions.

Remember the iconic song Pyar Hua Iqrar Hua from Shri 420 (1955)? As Raj Kapoor and Nargis share an umbrella in the rain, they exchange tender glances, unaware of the chaiwala nearby, savouring his own cup of tea and watching the romance unfold.

In Raanjhanaa (2013), for example, Kundan (Dhanush) spends countless hours at the tea stall, not just drinking chai but plotting his next steps. The tea stall is where friendships blossom, secrets are spilled, and life, quite simply, unfolds.

Tea moments that make a mark

An unforgettable scene that brings tea into the spotlight is from the vintage film Kundan (1955). As the characters gather at a lively roadside hotel, a friendly server chimes in with unmatched enthusiasm, Aao hamare hotel mein chai piyo jee garam. Biscuit kha lo naram naram! The scene unfolds playfully as his cheerful call sets the backdrop, making tea and comfort food the quiet heroes of this charming moment that invites everyone to relax and feel at home.

Likewise, in Chennai Express (2013), Rahul (Shah Rukh Khan) stepping off a train for a quick chai leads to an entire adventure. What starts as a simple cup of tea triggers a series of hilarious and chaotic events, reminding us that in Bollywood, even a cup of chai can change everything.

Tea: A symbol of comfort and connection

Tea in Bollywood is not just a prop; it is a symbol of connection and comfort.

In Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham (2001), a simple scene where Amitabh Bachchan’s character Yash shares a quiet moment with Nandini (Jaya Bhaduri) over tea exemplifies how chai fosters a warm connection between family members.

Another such instance is from English Vinglish (2012), where Shashi (Sridevi) finds solace in brewing and serving tea. Her love for tea helps her bond with those around her, becoming a tool for her to regain confidence and independence.

Iconic movie scenes featuring chai

Bollywood has immortalised chai in numerous scenes, reflecting its role in everyday life. Here are ten standout moments where chai took centre stage:

Ram aur Shyam (1967): A nervous Ram (Dilip Kumar) fumbles with trembling hands as he serves tea to Anjana (Waheeda Rehman), the moment filled with unspoken emotions and anticipation.

Bawarchi (1972): Rajesh Khanna’s character Raghu gathers a dysfunctional family around cups of chai, uniting them in a ritual that symbolises peace and harmony.

Gol Maal (1979): Bhavani Shankar (Utpal Dutt) unexpectedly visits Ram Prasad (Amol Palekar) to uncover the truth about Kamala Srivastav (Dina Pathak) as his mother. While enjoying a cup of tea, the deception of the twin brother, Lakshman Prasad (also Amol Palekar), continues under the guise of warmth.

Baazigar (1993): The character Babulal’s (Johny Lever) declaration, Khaas maukon par khaas chai (Special tea for special occasions), underscores how chai can make or break important moments, even a marriage proposal.

Andaz Apna Apna (1994): Amar’s (Aamir Khan) landmark line, Do dost ek pyale mein chai piyenge, isse dosti badti hai (Two friends sharing a cup of tea strengthens friendship), is the perfect example of how tea fosters relationships in Bollywood.

Parineeta (2005): Tea serves as a bridge for important conversations, as a simple chai scene between Shekhar (Saif Ali Khan) and his mother Rajeshwari Roy (Surinder Kaur) shows how chai facilitates pivotal discussions.

Sarkar (2005): Subhash Nagre (Amitabh Bachchan) sipping tea while holding a saucer, backed by the intense Govinda Govinda soundtrack, shows the power and confidence associated with something as simple as tea.

Wake Up Sid (2009): Ranbir Kapoor’s character Sid takes Konkona Sen Sharma’s character Aisha to Marine Drive, where they share chai by the sea, building an intimate bond over the beverage.

Barfi (2012): A reunion over chai between Murphy (Ranbir Kapoor) and Shruti (Ileana D’Cruz) beautifully highlights how even unresolved love can find rekindling over a cup of tea.

Khoobsurat (2014): The simplicity of chai in a roadside stall helps break down the royal façade of a prince, Yuvraj Vikram (Fawad Khan), allowing a deep connection with a commoner, Mili (Sonam Kapoor).

Chai, a symbol of everyday life in Indian cinema

From budding romances to familial reconciliations, tea has long played a role in some of Bollywood’s most cherished moments. Here, chai isn’t just a drink. It is a symbol of warmth, love, and bonding.

The next time you sip your cup of chai, remember, you are part of a cultural phenomenon that has graced the silver screen for decades, bringing characters together in ways only Bollywood can.

About the author

With decades in the mad, mad world of advertising, Anupam Ganguli is synonymous with creativity, strategy, and storytelling. A true adman, author, and design buff, he’s the wizard behind landmark campaigns and 360-degree solutions that have shaped and birthed countless Indian brands. His flair does not stop at ads, though. He has named iconic structures across Gurugram, Faridabad, Kaushambi, and Noida, leaving his mark on more than just billboards. When it comes to storytelling and design, Anupam brings brands to life, setting the benchmarks for advertising excellence, often with wit and style.

Notes

- The collage used here has only been made for representational purposes. All the images therein are owned by their respective copyright holders.

- A version of this article had first been posted by Anupam Ganguly in The Reviewer Collective group on Facebook. His permission to publish it here is gratefully acknowledged.

Gulzar at 90: The Master’s 30 Best Lyrics From a Six-Decade Career: Guest Post by Devarsi Ghosh

Posted in The Magic of Movies!, tagged Birthday, Bollywood, Gulzar, Lyricists, Movies on August 25, 2024| Leave a Comment »

Gulzar once said lyrics should “amaze or amuse”, or otherwise no one would care. In his six-decade career as a poet-lyricist, he certainly stuck to this principle.

His best work in the first half of his career was with R.D. Burman. After a lull following Burman’s death, with composers like A.R. Rahman, Vishal Bhardwaj and Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy entering his world, his lyrics gained a new ferocity, as filmmakers and their gradually evolving subject matters gave him room to experiment and push the envelope.

Here are only some of Gulzar’s best-written (not necessarily his most successful) songs.

‘Mora Gora Ang’, Bandini (1963)

A textbook example of how Gulzar turns a traditional love song into something ethereal: evoking “Shyam”, which means evening as well as the Hindu god of love Krishna. He writes: “Mora gora ang lai le, mohey shyam rang dei de / Choop jaungi raat hi mein, mohey pee ka sang dei de” (‘Take my fair body, colour me as dark as shyam / I will hide myself in the night, grant me the company of my beloved’).

‘Humne Dekhi Hai Un Aankhon Ki Mehakti Khusboo’, Khamoshi (1969)

Can you see the fragrance of the eyes? Gulzar can. This was among one of Gulzar’s earliest songs where a sensory experience is accorded to a body part to which it is foreign. But what makes this song work, after its unorthodox opening, are the graceful lines that follow.

‘Haal Chaal Theek Thaak Hai’, Mere Apne (1971)

Among one of Gulzar’s earliest political songs, the lines here are caustic and timeless. In one verse, he refers to the ruling class with “makaanon pe pagdi waale sasur khade” (‘Tough father-in-laws stand atop buildings’), which is rhymed with “koi in buzurghon se kaise lade?” (‘How do we fight these old men?’).

In another, he explains the food-and-money situation with the image of a roti rolling down the street followed by a silver coin, but a kite flies away with the roti and a crow escapes with the coin.

‘Musafir Hoon Yaaron’, Parichay (1972)

Gulzar creates some really simple but evocative images in this song about a wanderer. He writes, ‘if one path didn’t work out, another came by, and sometimes the path followed me the way I turned’. Then he writes: ‘sometimes the day beckoned me there, the night called me there, I made friends with both dawn and dusk’.

‘O Majhi Re’, Khushboo (1975)

Rivers, shores and boatmen are recurring images in Gulzar’s lyrics, and this is perhaps his most definitive song in that respect. Among the stand-out metaphors here is Gulzar’s description of lonely wanderers as eroded strips of land floating in search of a shore.

‘Dil Dhoondhta Hai’, Mausam (1975)

In contrast to the upbeat tune, Gulzar’s free verse about reminiscing an old love is rather poised and graceful.

The lyrics perhaps may be better appreciated if read as a poem. Some pleasant imagery here: “Jaadon ki narm dhoop aur aangan mein let kar, aankhon pe kheench kar tere daaman ke saaye ko / aundhe pade rahe kabhi karvat liye huye” (‘I lay prone in the courtyard under the soft shade of trees, drawing your shadow over my eyes, sometimes twisting and turning’).

‘Tere Bina Zindagi’, Aandhi (1975)

Once again with a romantic song, Gulzar’s powerful introduction sets up and defines the sort of love to be explored. This time, there’s affection, but between old souls: ‘Without you, I have no complaints with life, but life isn’t life without you’, he writes.

‘Masterji Ki Aa Gayi Chitthi’, Kitaab (1977)

Gulzar’s reputation for wacky, out-there lyrics is surely courtesy his work with the post-1990s composers, but some of his particularly eccentric work with R.D. Burman deserves credit for sending him down that road.

In this song, among other things, out of the masterji’s letter pops out a betel leaf-chewing cat wearing shades and a mosquito with a mountain-carrying moustache.

‘Ek Akela Iss Shahar Me’, Gharaonda (1977)

A terrific song about urban loneliness. Had Travis Bickle heard this, he may have calmed down and not attempted assassinations and gunfights. Among its most haunting lines about the indifferent city: “Din khali khali bartan hai aur raat hai jaise andha kuaan” (The days are like empty vessels, the nights are a bottomless well).

‘Aaj Kal Paon Zameen Par’, Ghar (1978)

The lightness of touch in Gulzar’s lyrics complements the optimistic yet modest hopes of a young blooming romance. In a standout verse, Gulzar writes, ‘whenever I held your hand and looked, people said it’s only the lines on your palm, but I saw two destinies coming together’.

‘Phirse Aaiyo Badra Bidesi’, Namkeen (1982)

Splendid imagery abounds in this haunting song filled with longing. With mentions of clouds, a lake, a terrace, a peepal tree, a garden, a small bridge and so on, he magnificently creates a psycho-geography that gets engulfed in yearning with each passing line.

‘Mera Kuchh Samaan’, Ijaazat (1987)

Gulzar’s ultimate breakup/heartbreak song, but such a facetious description hardly does justice to the brilliance of ‘Mera Kuchh Samaan’. From the simple idea of wanting your stuff back from your ex-lover’s house, Gulzar creates a tapestry of the haunted memories of a relationship that once was.

‘Khamosh Sa Afsana’, Libaas (1988)

This feels like a song created out of ideas and metaphors Gulzar has turned to before in other songs, for example, ‘Humne Dekhi Hai In Aankhon Ki Mehakti Khushboo’, which is concerned with love that is best left unexpressed, and ‘O Majhi Re’, with its metaphors of river as life and shore as companion. It is the combination of these two ideas that lend the song its potency.

‘Chhod Aye Hum’, Maachis (1996)

A great song that documents the emotions and memories one has for their homeland and the endless gloom that follows when it is ravaged. The best line in the song goes, “Ek chota sa lamhaa hai, jo khatam nahi hota / Main laakh jalata hoon, yeh bhasm nahi hota”. (‘A small moment in time that just doesn’t end / I keep setting it on fire, but it is never burned down’).

‘Dil Se Re’, Dil Se.. (1998)

An absolutely bombastic declaration of love, in contrast to the subdued grace of the earlier romantic songs in this list. Just a sigh of the heart causes the sun to shine, the mercury to melt and a storm to rise, Gulzar writes in the opening verse. Then he creates some extraordinary imagery about two stray leaves in another verse, which gets better the more you listen and contemplate the lines.

‘Goli Maar Bheje Mein’, Satya (1998)

Don’t think, just shoot, for if you think, you die – Gulzar spins a rollicking fun song out of this simple gangster’s code of living. Gulzar is writing from the perspective of absolute scoundrels, using their lingo, and despite the coarseness of the words (or because of it), the message is communicated sharply.

‘Ghapla Hai Bhai’, Hu Tu Tu (1999)

Everything is a scam, Gulzar writes, in this satirical song through which he takes potshots at the political class. Gulzar drops the mocking tone in the final verse and embraces the true sadness of the subject matter: “… ghiste ghiste fat jaate hai juton jaise log bechaare … pairon mein pehne jaate hai, jalse aur jalluso mein”. (‘People are like shoes, tattered from overuse, worn at celebrations and processions’).

‘Hum Bhul Gaye’, Aks (1999)

If we are to strip the song of the film’s context, Gulzar’s lyrics, which depict an experience of feeling disassociated from oneself, might just be about depression. He writes, “Umeed bhi ajnabee lagti hai aur dard paraya lagta hai / Aaine me jisko dekha tha bichda huwa saya lagta hai.” (‘Hope seems like a stranger and pain feels foreign, the one I see in the mirror seems like a shadow separated from me’).

‘Haath Choote’, Pinjar (2003)

Gulzar’s lyrics are a 101 on how to deal with relationships that are about to or have completely run their course. He writes, ‘even if the holding of hands gets loose, do not end ties’. Then he writes, ‘if one has to indeed leave, don’t break your heart for them’.

‘Piya Tora Kaisa Abhimaan’, ‘Raincoat’ (2004)

In a song essentially about endlessly waiting for your beloved, the allusions to Hindu traditions and myths lend it a timeless folkish quality. Gulzar weaves the angst of pining with the images of Radha-Krishna’s romance under the kadam tree, kahars carrying a palanquin, bathing in the Jamuna for absolving one’s sins and wearing the “garal saman” or poison-like mark of sandalwood on the forehead to embrace a hermit’s life as one’s lover won’t ever return.

‘O Saathi Re’, Omkara (2006)

As much as choosing the best lyrics in Omkara is a toss-up between the ornate raunchiness of ‘Namak’ and the sublime beauty of ‘O Saathi Re’, the warmth in the latter’s description of mutual affection is more effective than the cleverness of the former’s innuendos. Gulzar draws some lovely images in O Saathi Re, particularly in a verse that follows a couple fishing on a riverbank on a red evening.

‘Ay Hairathe’, Guru (2007)

Like moments in ‘O Saathi Re’ and a bunch of other love songs, like the ones from Ghar and Ijaazat, Gulzar is a master at highlighting the particularities of a relationship, mentioning specific details and giving the relationship a lived-in quality. ‘Ay Hairathe’ is just one more example in which Gulzar brings grace to the intense cuteness of a marriage’s honeymoon years.

‘Kaminey’, Kaminey (2009)

Gulzar writes, ‘everyone and everything is damned, including me, my hopes, my dreams, my friendships’, the list goes on. In a song where self-pity is the only conclusion of introspection, there are moments of cruel beauty, such as a verse where Gulzar writes, “Jiska bhi chehra cheela, andar se aur nika / Masoom sa kabootar / naacha to mor nika”. (‘I found someone else everytime I scratched a face’ / ‘An innocent pigeon danced, turned out to be a peacock’).

‘Dil To Bachcha Hai Ji’, Ishqiya (2010)

What’s great about the lyrics here is how from a definite premise – that of an old man feeling young again because of love – Gulzar draws out all kinds of specific images and ideas that feel extremely effortless. There are no complex metaphors at work, nothing that’s tired and overused, and it all comes together so neatly.

‘Bekaraan’, 7 Khoon Maaf (2011)

There are some lovely moments in this romantic paean. There’s the part where Gulzar writes, ‘please see beneath your feet if something’s stuck … it’s just time, please ask it to move along’.

But then written from the perspective of an abusive husband, the line “Kya laga honth tale, jaise koi chot chale” (‘What’s that under your lips, looks like a bruise’), gives the song a sinister edge.

‘Heer’, Jab Tak Hai Jaan (2012)

Yet another song about pining, but how to keep it fresh? Gulzar brilliantly blends two tragic romances: Heer-Ranjha and Mirza-Sahiban. He writes, ‘don’t call me Heer’ (who doesn’t get to build a home with her lover Ranjha, as she is married off, and both die before they can be united), ‘for I’ve become Sahibaan, and Mirza will bring a horse and take me away soon’. (Mirza escaped with Sahibaan on his horse the night right before her wedding ceremony).

‘Khul Kabhi Toh’, Haider (2014)

Like ‘Bekaraan’, again an intense love song written from the perspective of a guy who is not quite there in his head.

Beautiful lines like “saans–saans sek doon tujhe” (‘breath by breath, I will heat you up’), lead up to violent imagery: ‘when I was kissing your earrings, a gulmohar tree kept dancing’ … ‘in the heat, I felt ‘why don’t I throw you into the fire of the burning gulmohar’’.

‘Kill Dil’, Kill Dil (2014)

There are fantastic images and metaphors all throughout this song, which tells the story of two daredevil gunslingers. Gulzar himself recites their introduction: ‘Here come two bastard sons of darkness, walking down a coal-black road … they were raised drinking blood … they neither have skies overheard nor ground underneath … perhaps their life was crushed, this is their story’.

‘Patli Gali’, Talvar (2015)

A fun sardonic take on how torturous the legal system is for the common citizen, ‘Patli Gali’ is filled with delightful lines. For example, in the “patli gali” (narrow lane), Gulzar writes, ‘bald men sell combs, while lawmakers sell the ropes twisted round their [the people’s] necks’.

‘Aave Re Hichki’, Mirzya (2016)

Gulzar ties up the folk myth of hiccups occuring when one is remembered by their beloved with the widely held belief of their occuring due to a dry throat. But going past this conceit, Gulzar yet again evocatively describes the sorrow of longing, drawing in elements of the geography of the story, as he did with ‘Phirse Aaiyo Badra Bidesi’.

About the author:

Devarsi Ghosh loves to write on films, books and music when he is not working on his screenplays.

Notes:

- August 18 is Gulzar’s birthday.

- This article first appeared on The Wire: https://thewire.in/the-arts/gulzar-at-90-his-30-best-lyrics.

- The author’s permission to reproduce this article here is gratefully acknowledged.

Related Posts:

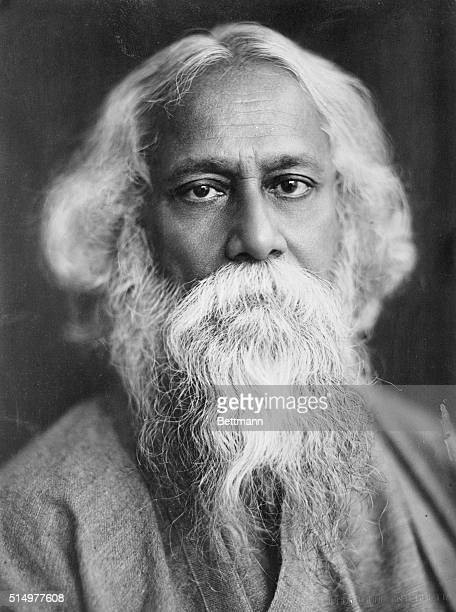

Tagore’s Twilight: A Cinematic Ode to the Bard’s Legacy: Guest Post by Suryamouli Datta

Posted in The Magic of Movies!, tagged Adapatations, Bollywood, Gitanjali, Literature, Movies, Rabindranath Tagore, Satyajit Ray, Tapan Sinha on August 2, 2024| Leave a Comment »

Introduction

As the sombre mist of mortality settles upon the world, I find myself, along with countless others, lost in the labyrinth of thought, pondering the enigmatic fate that had beckoned the great poet, Rabindranath Tagore, to the realm of the eternal, on the 7th of August, 1941. For the 83rd time, we are forced to confront the stark reality of his passing, and the weight of his absence settles upon our collective conscience like a shroud. And yet, as we gaze upon the canvas of his extraordinary life, we cannot help but wonder what wondrous tapestry of words and ideas the Bard of India might have woven had he remained among us, a tantalizing what-if that haunts us like a persistent melody.

Looking back to early days

As a child of tender years, his idealistic nature found expression in a paean to the raindrops’ embrace upon leaves, their gentle patter evoking the rhythmic swaying of an elephantine behemoth –

“Water pours, leaves dance,

Crazy elephant’s head sways in a trance“

To attempt to encapsulate his colossal contribution to the arts would be like trying to capture the sun in a teacup. Like a literary Gargantua, he devoured every realm of culture, leaving behind a Gargantuan feast of creative output.

His ‘Nobel’ contribution

The year 1913 was a moment in the annals of literary history when the world finally awakened to the profound significance of Rabindranath Tagore’s contributions to world literature. It was as if the veil of ignorance had been lifted, and the international community beheld, with a mixture of wonder and reverence, the sheer brilliance of the Bengali bard’s thoughts. And we, as Indians, were filled with a sense of pride, nay, a deep-seated sense of ownership, for it was our own Tagore who had been instrumental in illuminating the path of human understanding.

It is worth noting that Tagore himself had taken the initiative to translate his creation, ‘Gitanjali’, into the English language, thereby rendering his exquisite and sensitive verse accessible to a global audience. The response was nothing short of astonishing, as the world was left agog at the beauty and profundity of his poetry. And it was none other than Thomas Sturge Moore, that erudite British poet, author, and artist, who had the foresight to recommend Tagore’s name for the Nobel Prize, even before the year 1913 had dawned.

Tagore in Bollywood

However, in this discourse, our attention shall be directed solely to the instances wherein the cinematic artisans of Bollywood have sought to translate the essence of his creations into the vibrant medium of visual storytelling. It is not easy to capture the nuances of a work of a literary kind in the medium of moving images. As we shall see, while some movie directors have done it very diligently, others have taken a few liberties with the original narrative. Nevertheless, let us consider some such endeavours where his words have found expression on the silver screen, making them reach out to a much wider audience.

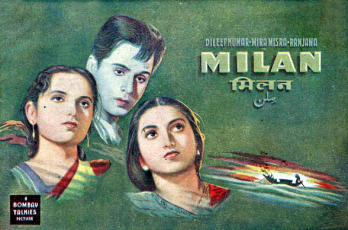

Milan (1946)

Adapted Story: Noukadubi (The boat wreck)

Director: Nitin Bose

Cast: Dilip Kumar, Mira Misra, Ranjana, Moni Chatterjee, S. Nazeer

Synopsis: In the arcane tapestry of 1905 Calcutta, a city pulsating with intellectual fervour, Ramesh, our cogent protagonist, becomes ensnared in a labyrinth of societal dogma and the yearnings of the heart.

Dilip Kumar imbues Ramesh, a fledgling law student, with a palpable yearning for Hemnalini, portrayed by the enigmatic Ranjana. However, their burgeoning romance is stymied by the machinations of Akshay, menacingly brought to life by Pahari Sanyal, thus weaving a thread of intrigue into the narrative.

As the relentless tendrils of fate interlock, familial duty and the dictates of the heart collide. Ramesh is summoned back to his ancestral village, setting in motion a whirlwind of events characterized by mistaken identities and emotional tempests. Amidst this turmoil, Ramesh’s virtuous aspirations are put to the test as he grapples with the precarious equilibrium between obligation and amour, a timeless theme in the grand theatre of life.

Upon his return to Calcutta, Ramesh’s noble efforts to enlighten Kamala, his unanticipated bride, lend an intricate layer to the unfolding tale. The reverberations of Ramesh’s clandestine union resonate throughout the hallowed halls of society, threatening to shatter his impending marriage to Hemnalini.

As tensions escalate to a fever pitch, the stage is set for a grand denouement, wherein truths are elucidated, hearts are mended, and love emerges victorious, transcending the constraints of adversity.

The Music: Verily, the musical composition of this cinematic endeavour was undertaken by the esteemed Anil Biswas. The lyrics, crafted with utmost precision and elegance, sprang forth from the minds of the renowned Pyare Lal Santoshi and Arzu Lakhnavi.

Parul Ghosh, a vocal virtuoso who lent her dulcet tones to a significant portion of the filmic arias, shared a familial bond with Anil Biswas, being his sibling of less advanced years. Historia attests to her as one of the inaugural exemplars of that novel method of sonic preservation known as playback singing within our realm of cinematic entertainment.

Geeta Dutt, another vocalist of exceptional talent, graced the film with her mellifluous contributions.

Trivia: In a spirit of dialectical inquiry, it is imperative to elucidate that the cinematic narrative of this film emanated from the pen of Sajanikanta Das, editor of Shanibarer Chithi (Saturday’s Letter). Das, a man possessed of a keen intellect and a mordant wit, had previously directed his critical gaze upon the esteemed Rabindranath Tagore. With a discerning eye, he had dissected Tagore’s literary aesthetics and his profound societal influence, finding them wanting.

Ghunghat (1960)

Adapted Story: Noukadubi (The boat wreck)

Director: Ramanand Sagar

Cast: Bharat Bhushan, Pradeep Kumar, Bina Rai, Asha Parekh

Synopsis: In a tale akin to Milan’s classic narrative, the annals of modernity unveil a poignant drama. A young man, Ravi, faces an agonizing dilemma when his parents demand that he sever his affection for Laxmi and marry another. With a heavy heart, he acquiesces to their wishes.

As fate would have it, a fateful train journey brings together a group of newlyweds, including Ravi and his bride. Tragedy strikes and the train is engulfed in a catastrophic accident. Ravi awakens to find an unconscious bride lying beside him. Mistaking her for his own wife, he transports her to his abode.

Upon realizing the demise of his true wife, Ravi is horrified to discover that the bride he has brought home is a different lady named Parvati. Tormented by guilt and compassion, he embarks on a desperate search for her husband, Gopal.

Unbeknownst to Ravi, Parvati had already stumbled upon the truth and made her escape. Seeking solace, she wandered aimlessly until she fell into the river Jamuna. Her fate led her to the doorstep of Gopal’s residence, where she encountered his brother, Manohar, who had lost his eyesight in the accident.

Torn between her newfound duty to care for Manohar and her longing to reunite with Gopal, Parvati remained silent about her true identity. A web of secrets and unspoken truths now intertwined their lives, leaving them adrift in a sea of uncertainty.

Music: The renowned music maestro Ravi brought forth the essence of Shakeel Badayuni’s exquisite lyrics on the silver screen. The ten melodious compositions were rendered by such legendary artists such as Mohd. Rafi, Asha Bhosle, Lata Mangeshkar, and Mahendra Kapoor. Among these, stand-out gems like Lata Mangeshkar’s rendition of ‘Lage Na Mora Jiya’, Mohd. Rafi’s soulful ‘Insan Ki Majbooriyan’, Asha Bhosle’s enchanting ‘Gori Ghunghat Mein’, and the mesmerizing duet of Mahendra Kapoor and Asha Bhosle in ‘Kya Kya Nazaray Dikhati Hai Ankhiyan’.

Kabuliwala (1961)

Adapted Story: Kabuliwala

Director: Hemen Gupta

Cast: Balraj Sahni, Sonu, Usha Kiran

Synopsis: In the realm of human narratives, we encounter a departure from convention—a tale in which the traditional roles of “boy” and “girl” are defined differently, “boy,” an elderly gentleman, finds himself interacting with a diminutive “girl” of five years of age, reminiscent of the incongruous coupling in P.G. Wodehouse’s “Lord Emsworth and Girlfriend.” However, this narrative possesses a distinctiveness that renders it a tale wholly its own.

Rahamat, a peripatetic merchant from Afghanistan, ventures to India seeking to peddle his wares. Here, he makes the acquaintance of Mini, a young lady of tender years. As their interactions deepen, a profound bond forms between them, akin to that of a father and daughter. Rahamat, reminded of his own daughter of Mini’s age, finds his paternal instincts stirring.

Circumstances conspire against them, and Rahamat is unjustly incarcerated. Upon his release, he seeks to reunite with Mini, unaware that the passage of time has wrought a significant change in her appearance. Mini, now a young woman, has no recollection of her former companion.

Grief-stricken, Rahamat departs India with a forlorn hope that his lost daughter may yet recognize him upon his return. Such is the nature of this enigmatic tale, where love and longing collide in a poignant exploration of the complexities of human relationships.

Music: Salil Choudhury, a veritable polymath, has bestowed upon us an ethereal symphony that perfectly encapsulates the narrative upon which it rests. In my humble estimation, there is no individual more adept at translating the Bengali soul into the universal language of music than this esteemed composer.

Furthermore, the illustrious voices of Hemant Kumar, Mohd. Rafi, Manna Dey, and Usha Mangeshkar serve as veritable conduits for the emotive lyrics penned by Prem Dhawan and Gulzar. Their vocal artistry transcends the realm of mere performance, becoming an integral thread in the tapestry of this cinematic masterpiece. Personally speaking, the “Ganga” song by Hemant Kumar is my all-time favourite!

Trivia: The Bengali iteration of the film was helmed by Tapan Sinha, a cinematic visionary whose repertoire extended beyond the hallowed borders of our country. His masterful direction of such seminal works as “Sagina” and “Zindagi Zindagi” has indelibly etched his name in the annals of cinematic history. To this humble observer, his unparalleled versatility renders him the paramount cinematic luminary of our times.

Uphaar (1971)

Adapted Story: Samapti (The Ending)

Director: Sudhendu Roy

Cast: Swarup Dutta, Jaya Bhaduri, Suresh Chatwal, Nandita Thakur

Synopsis: The eternal entanglements of the human heart! In the sweltering metropolis of Calcutta, a most intriguing tale of love, duty, and, dare I say, a pinch of mayhem unfolds. Our protagonist, Anoop, a law student with a mind as sharp as a razor, finds himself ensnared in the time-honoured tradition of arranged matrimony. His widowed mother, no doubt with the best of intentions, sets her sights on the lovely Vidya, a neighbour with a face as fresh as the morning dew.

But, alas, fate has a way of playing the mischief-maker. Upon making the acquaintance of Vidya, Anoop’s heart is suddenly hijacked by none other than Minoo, a rustic beauty from the village, with a smile that could charm the birds from the trees. In a most unbecoming display of defiance, Anoop defies his mother’s carefully laid plans and instead takes Minoo as his bride.

Now, it’s not long before the newlyweds discover that Minoo’s domestic skills are, shall we say, somewhat lacking. The poor dear can’t boil water to save her life, and Anoop’s mother, God bless her, is left to wonder if she’s made a grave mistake in letting her son marry this…this…Minoo.

The inevitable friction ensues, and Anoop, in a fit of exasperation, absconds to Calcutta, leaving Minoo to her own devices. But, as the days turn into weeks, Minoo’s love for Anoop begins to simmer, like a potent curry left to stew. She takes it upon herself to pen a heartfelt letter, a cri de coeur, if you will, only to have it met with deafening silence.

Still, undeterred by the setbacks, Minoo’s love for Anoop remains unwavering, a beacon of hope in the midst of marital turmoil. And it is at Anoop’s sister’s humble abode in Calcutta, a veritable haven of familial warmth, that the star-crossed lovers finally reunite, their love stronger and more resilient than ever.

As I see it, Minoo’s carefree spirit and boyish charm evoke the irrepressible Maria of ‘The Sound of Music’, yet whereas Maria had the solace of the Mother Superior at the Abbey who grasped the essence of her personality and encouraged her to ‘Climb every mountain…’, Minoo wandered, unguided, misunderstood and alone. It’s a difference that strikes a poignant chord.

Music: As I recall, the melodies that wafted through the evening air were the handiwork of the esteemed duo, Laxmikant Pyarelal, whose mastery of the musical arts is renowned far and wide. And, it was the legendary vocal triumvirate of Mohd. Rafi, Lata Mangeshkar, and Mukesh who lent their golden voices to the proceedings, imbuing the entire affair with a sense of grandeur and elegance.